In 1928, Irving Fisher published The Money Illusion (seriously, buy it – it’s only $7.95), which discussed the human fallacy of thinking about things in the nominal currency of your home country instead of in terms of purchasing power. The concept phrase “money illusion” was coined by legendary investor and economist John Maynard Keynes.

The easiest way to think about the money illusion is a phrase Warren Buffett has proclaimed: It isn’t how many dollars you have, but how many “cheeseburgers you can buy”. In other words, if stocks double but so does the price of milk, gas and cornflakes, you haven’t actually gained anything in real net worth.

The easiest way to think about the money illusion is a phrase Warren Buffett has proclaimed: It isn’t how many dollars you have, but how many “cheeseburgers you can buy”. In other words, if stocks double but so does the price of milk, gas and cornflakes, you haven’t actually gained anything in real net worth.

The money illusion phenomenon is what led to the so-called “Silent Crash” of the Dow Jones Industrial Average during the 1970’s when the Dow had barely budged over the previous ten years but prices had doubled, resulting in a roughly 50% decline in purchasing power!

Irving Fisher’s German Shopkeeper and The Money Illusion

In the opening pages, Irving Fisher speaks of a German shopkeeper who illustrated his point – that nominal currencies are meaningless – by recounting an experience he had following the rapid depreciation of the German Mark following World War I.

When I talked with her [the shopkeeper] the inflation had gone on until the mark had depreciated by more than ninety-eight per cent, so that it was only a fiftieth of its original value (that is, the price level had risen about fifty fold), and yet she had not been aware of what had really happened. Fearing to be thought a profiteer, she said: “That shirt I sold you will cost me just as much to replace as I am charging you.” before I could ask her why, then, she sold it at so low a price, she continued: “But I have made a profit on that shirt because I bought it for less.”

She had made no profit; she had made a loss. She thought she had made a profit only because she was deceived by the “Money Illusion.” She had assumed that the marks she had paid for the shirt a year ago were the same sort of marks as the marks I was paying her, just as, in America, we assume that the dollar is the same at one time as another. She had kept her accounts in what was in reality a fluctuating unit, the mark. In terms of this changing unit her accounts did indeed show a profit; but if she had translated her accounts into dollars, they would have shown a large loss, and if she had translated them into units of commodities in general she would have shown a still larger loss – because the dollar, too, had fallen.

The reason I am thinking about this today is the earlier essay I wrote about how young investors are fleeing from stocks and parking their money in bonds and cash equivalents.

Fisher points out that two books, Edgar Lawrence Smith’s “Common Stocks as Long Term Investments” and Kenneth Van Strum’s “Investing in Purchasing Power” demonstrated how many long-term bond investors were not, in fact, safe because they were losing purchasing power in inflationary terms. What they thought was interest income was merely a return of principal, often for less than they paid the company to whom they lent the money.

The Dollar vs. Gold and The Money Illusion

What counts is what money can buy. As General F. A. Walker, economist, said and is reference in Fisher’s book, “money is as money does” or “the dollar is what the dollar buys”.

Often, well meaning people think of the gold standard as being vital to protecting the currency. But they are still making a mistake based upon the money illusion. Let me offer a clue as to the reason.

When Fisher wrote his treatise in 1928, a $1 bill in the United States was exchangeable for exactly 23.22 grains of pure gold. It had been this way since 1837 since the relationships were fixed. The two figures, as the author writes, “mutually imply one another”. That is, an ounce of gold would always be $20.67 because a single U.S. dollar was exchangeable for 23.22 grams of gold. As gold fluctuated, so did the dollar and visa versa but they relationship and ratio between the two remain unchanged.

During that same 91 year period, inflation caused the dollar to depreciate from $1.00 to $0.64 in terms of purchasing power. Looking at it from the inverse perspective, it would take $1.51 in 1928 to buy what $1.00 would in 1837. That means inflation ran at approximately 45 basis points, or 0.45% annually for nearly a century. That is, in 1837 gold was $20.67 per ounce. In 1928 gold was $20.67 per ounce. Likewise, 23.22 grams of gold was $1 in both 1837 and in 1928. But in 1928, it was worth much less money than it was in 1837.

Does that low inflation rate seem attractive? It would be had it been a steady rise. Instead, while on a fixed measure of gold exchange, the United States experienced substantial inflation followed by bouts of crippling deflation driven by gold mining and scarcity.

Irving Fisher does a masterful job explaining this:

Our fixed-weight dollar is a poor substitute for a really stable dollar as would be a fixed weight of copper, a fixed yardage of carpet, or a fixed number of eggs. If we were to define a dollar as a dozen eggs, thenceforth the price of eggs would necessarily and always be a dollar a dozen. Nevertheless, the supply and demand of eggs would keep on working. For instance, if the hens failed to lay, the price of eggs would not rise [in dollars] but the price of almost everything else would fall. One egg would buy more than before [because they are more rare]. Yet, because of the Money Illusion, we would not even suspect the hens of causing low prices and hard times.

This is one of the reasons that I think it is incredibly beneficial for investors to measure equities in gold, silver, barrels of crude oil, water, wheat, and other commodities. It is about relationships to one another and purchasing power. All that counts is purchasing power.

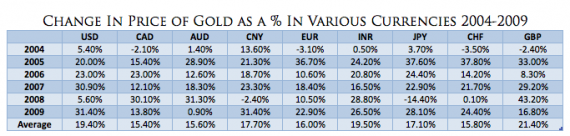

Don’t believe it? Consider this chart:

As you can see from the chart, in 2008 during the global financial crisis, gold was down 14.4% in Japan and up 43.2% in Great Britain! Thus, whether it was a great year or a terrible year for your gold investment depends upon the currency into which you wanted to convert your gold holdings (because landlords, restaurants and phone companies don’t accept bullion as payment – you must use cash).

This underscores my fundamental belief in Buffett’s “cheeseburger” test. What matters is purchasing power for your household. Each year, you want to be able to buy more cheeseburgers than you could the year before, whether it is with dollars, sea shells or gold bullion. Purchasing power is all that matters in economics.

[mainbodyad]Fisher goes on to point out that in the generation prior to his writing the book, the dollar’s value had been unstable for the reason of the money illusion despite the gold standard:

An expansion in the dollar’s worth of nearly four fold within a generation, and equal shrinkage within a still shorter time, followed by another great expansion in a little more than a year, shows that our dollar has been far from stable. That is to say, even in the United States, a gold standard country, money changed in buying power just as truly, even if not as much, as it did in the paper standard countries.

As painful as America’s financial policies have been in terms of the dollar losing value, the only thing more painful would be a rapid oscillation between inflation and deflation because most people use debt in fixed rate terms. If you borrowed $100,000 for a house and the dollar increased in value by 400% so that you were paid 1/4 as much – in dollars – at your job, you might still be able to buy the same milk, butter, and cheese quantities but your mortgage payment, which was fixed, effectively doubled.