As we approach the end of 2014, I’m looking back on the year. One of the major changes from an investing perspective what a modification Aaron and I made in the investment policy manual. That doesn’t happen often. We added a handful of companies to the list of permanent business; those companies we consider so exceptional that we buy them with no intention of ever selling. The Hershey Company was one of those firms.

One of the biggest mistakes of my investing life, and a lesson that took me more than 20 years to correct, has been the refusal to pay a slightly-higher-than-I’m-comfortable-with price for a handful of operating assets that have truly extraordinary economics. You’d think I wouldn’t have been so foolish given that the people who made up my childhood reading – Philip Fisher, Peter Lynch, Charles Munger, Warren Buffett, and many of the other great wealth managers of all time – constantly warned against this temptation in their writings and interviews. The ignorance of youth somehow made me immune to their entreaties, I suppose, and it took me a long time to come around to the idea that what looks like a high sticker price can be a good deal, in certain, rare circumstances. I think this shortcoming is inherent in a certain temperament. For those of us who like bargains, there’s an intellectual high from getting something for 30, 50, 70% off. It can be painful to pay full price. (Look at how we buy our cookware!) This can make it easy for us to miss out on something great because we were too busy counting pennies to grab the dollars of utility in front of us.

While Hershey’s flagship products are perhaps what the company is best known for producing, it actually holds the license to other chocolate lines such as Cadbury, Kit Kat, and Rollo. It owns one of the world’s premier high-end chocolate companies, Scharffen Berger, and has recently been acquiring international chocolate competitors to expand into India, China, and Mexico.

While I’ve done well in my career, I believe in spotting errors and correcting them. The fact I never pulled the trigger to acquire Hershey’s shares for the first 90% of my investment life is one of those mistakes. It wasn’t as if I had no exposure to it. It’s a firm that has been on my radar since I was a child. I remember reading its financials and studying news articles about it as a teenager in my high school’s computer lab, never able to make myself pull the proverbial trigger and add some to my collection of cash generating assets. (I can still see the piece in my head. A manager from a private asset management company called Neuberger Berman, which I had never heard of before, was talking about the reasons his rich clients were refusing to buy the technology stocks everybody else was fighting over, bidding up to the stratosphere. He used Hershey Foods Corporation, as it was then called, as an example of the type of stock he was having his wealthy clients purchase because they could keep it forever, the returns on capital making up for the 25x or so valuation ratio.) I was busy buying companies like Pier 1 or Saks back in those days, acquiring at one price and selling for a 50% gain, thinking how great it was I was making money. It was lucrative but short-sighted.

I wanted Hershey’s. I knew it was a great business. I just demanded it at 10x earnings. That day never came. Instead, the chocolatier kept generating its mouth-watering returns on capital and profits grew in tandem, the stock price going along with it.

To illustrate how this magical math worked, let’s take the most unfavorable year we can – the end of 1998 – when the stock was earning $1.15 per adjusted share, trading at an average annual p/e of 29.6 for the preceding twelve months. On the final trading day of 1998, nearly 17 years ago, the shares closed at $62.19 before splits. Factoring in all of the cash dividends that have been received, and adjusting for the stock splits that have occurred, this approximates a cost of around $21.74 compared to $99.80 today. That means every $100 you invested in a retirement account is now worth $459. That’s a 9.4% compound annual growth rate, crushing the 2.2% average inflation rate over the same period. Even better, this assumes you didn’t reinvest your dividends. Had you done so, your rate of return would have been much higher.

Meanwhile, the Vanguard S&P 500 index fund closed that same year at $113.95. Adjusted for dividends and splits, but likewise assuming no reinvestment of dividends, that works out to a cost of $85.91. Compare that to the current value of $192.20. That means the market as a whole turned every $100 into $224 or so, producing a compound annual rate of return of roughly 4.8% per annum, still beating the 2.2% average inflation rate but coming nowhere near the end wealth Hershey produced.

Only now, with the benefit of experience, do I understand how a business like Hershey, in 2014, at 27.13 times earnings with a 2.10% dividend yield can be cheaper than a business like Intel, which trades at 17.94x earnings with a 2.40% dividend yield. True, it’s no bargain – if you asked me to come up with a rough estimate, I’d say Hershey is probably worth around $90 per share, or about 10% less than the market price – but it’s still within a striking range small enough that it won’t matter 25 years from now. I couldn’t tell you with any reasonable probability what Intel will be worth 10 years from now, let alone 25 years from now. It would be a complete shot in the dark; to paraphrase one famous investor, somewhere between nothing and a whole lot more than it is today. Your guess is as good as mine. I may own it for a 3-5 year period if I think it is cheap, but it will never rank among the pantheon of the investment gods like Nestle or McCormick, Coke or Brown Forman.

I still believe it is wise to avoid things you don’t understand. There was a sort of naïve optimality in my refusal to purchase, at 15 or 16 years old, a company trading at nearly 30x earnings given I lacked the knowledge of accounting, finance, economics, and compounding to understand how it could be cheap. I knew that one of the biggest dangers to an investor, whether in real estate, stocks, bonds, or any other assets, was overpaying relative to the cash flows. That knowledge caused me to shy away from anything that seemed questionable. It served me extraordinarily well in life. Growing up, my father constantly reiterated from his own experience, “It’s not the good deals you get, it’s the bad deals you avoid that build your fortune.” In the compounding game, it’s better to miss out on something for the sake of protecting your capital than it is to swing for the fences and miss. While this philosophy caused me to pass on a business like Hershey from time to time, it saved me from countless other would-be disasters. In no small part thanks to my adherence to the discipline, I was able to sail through the dot-com bubble, the September 11th crash, the real estate bubble, and the subsequent Great Recession unscathed. At no point in my life did I ever lose a single night’s sleep worrying about our portfolio, nor what would happen if the stock exchange were to close for five years.

A Look at Last Year’s Earnings Helps You See What Makes The Hershey Company So Unique

Given this crowd’s propensity for numbers, it might help to run some figures. Let’s pull the most recent full annual results we can, which were for fiscal year 2013.

During that period, Hershey generated $7,146,000,000 in sales. After paying for the raw costs of cocoa, sugar, and the other things necessary to produce the product, it was left with $3,280,800,000 in gross profit. Then came the salaries, advertising expense, and other costs that are a necessary part of business, which took $1,922,500,000, along with $18,600,000 in realignment charges. This left $1,339,700,000 in pre-tax, pre-interest profits, or 18.7% of sales. Net interest expense is minimal in Hershey’s case, coming in at $88,400,000. Taxes, on the other hand, are fairly brutal compared to competitors like Nestle, which is treated more favorable by its home country of Switzerland. Hershey had to give up $430,800,000 to various governments, or 34.4% of all earnings. This left net income of $820,500,000.

The remarkable thing? When you back out the value of the intangible assets like the brand name and goodwill for acquisitions, the average assets required to produce those profits were only $4,262,684,000 for that same period. That means Hershey is capable of pumping out more than 19% after taxes on its average tangible capital and more than 31% before taxes and interest on its average tangible capital. This would be impressive enough in a single year. A nice business might be able to keep it up for five or ten years. But Hershey? Hershey was founded in 1894. This is what it does. The power of market acceptance, and demand, allows it to manifest those kinds of incredible results like clockwork because customers aren’t satisfied with anything else. They will pay for Hershey’s intellectual property. There is no reasonably close approximation for a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. If you want a Cadbury bar in the United States, you want a Cadbury bar. You’re not going to be satisfied with the knock-off brand as it doesn’t taste the same. If you crave a Kit-Kat, good luck finding something else like it. If you want a York Peppermint Patty, you aren’t going to be happy with a candy cane.

As icing on the cake, returns are actually better than they appear because more than half of the tangible capital consists of cash and other current assets, not heavy equipment and factories! The strength of the financial statements is obfuscating just how incredible the underlying economic engine is.

Add To These Returns the Benefits of a Controlling Shareholder Thanks to The Hershey Trust

On top of all of this, a majority of the company’s stock is still owned by The Hershey Trust. That means you not only get a controlling shareholder that can protect the firm from the influence of Wall Street, but you can be assured it has the long-term interest of the business as a core value because it depends on the dividends to fund The Milton Hershey School, which remains one of the best private schools in the world, teaching and housing nearly 2,000 orphans and underprivileged students. They need to grow profits, hike the dividend, and maintain a strong balance sheet to fulfill their mission and the corporate capital structure is arranged so that the regular stockholders get a 10% higher dividend rate than the trust does on its super-voting Class B shares. (We’ll talk about the dividend in a moment.) It’s hard to find a greater alignment of interests than that.

This unique arrangement started because of the hardship the company founder experienced in his youth. Milton Hershey had a challenging upbringing, going from feast to famine thanks to a father who was never able to secure much success. He was forced to give up on schooling in the fifth grade to help support himself. He married his wife, Catherine, and they tried to be entrepreneurs. Their first candy company went bankrupt. They tried again and, somehow, built North America’s premier chocolate maker.

Both Milton and Catherine wanted children badly but they were unable to conceive. Determined to use their wealth to make up for the things they never had, they decided to devote a huge portion of their fortune to building a school for poor, white, male orphans; kids who were just like Milton and who would have done much better had they only been given a chance in life. In 1909, Milton and Catherine donated the farm on which Milton grew up the newly formed school. Within a year or two, a small student body of ten students was attending. The school paid for their housing, meals, books; it trained them in a vocation, and gave them a head start in life. In exchange, the students attended church once a week and milked cows (the cow milking only stopped in 1989 when the focus changed from vocational training to college preparation). The school has not been without criticism – for example, it only allows those who are free from mental or emotional problems to attend because they are interested in giving those who would otherwise have done well but were born into bad circumstances the greatest probability of success, even if it means discarding anyone who doesn’t make the cut in a rather cold manner – but overall, it has been one of the greatest forces for good in the American education system since the country was established.

In 1915, Catherine died. Devastated, Milton signed over practically everything he owned to the school, including his two most valuable assets – his shares of The Hershey Company along with thousands upon thousands of acres of farmland on which they raised the cattle that produced the milk for the chocolate factory. The wealth was to be held in trust for the benefit of the students. For the next 30 years, he made chocolate and saw that the dividends and farm profits from his former assets were put to good use helping the boys. He also used the profits generated by the trust to benefit the community beyond the school itself. During the Great Depression, when work was sparse, he decided to construct The Hotel Hershey. It provided jobs at a time when there were none to be had.

In 1915, Catherine died. Devastated, Milton signed over practically everything he owned to the school, including his two most valuable assets – his shares of The Hershey Company along with thousands upon thousands of acres of farmland on which they raised the cattle that produced the milk for the chocolate factory. The wealth was to be held in trust for the benefit of the students. For the next 30 years, he made chocolate and saw that the dividends and farm profits from his former assets were put to good use helping the boys. He also used the profits generated by the trust to benefit the community beyond the school itself. During the Great Depression, when work was sparse, he decided to construct The Hotel Hershey. It provided jobs at a time when there were none to be had.

The last time we looked at The Hershey Trust, it held over $9 billion, practically all compounded from the original $60 million gift Milton made back in 1915 despite spending incredible sums of dividend income over the years educating tens of thousands of students. The trust document itself was written in such a way that any attempt to sell Hershey’s shares has to be approved by the Attorney General of Pennsylvania. Awhile back, when there was a push to diversify the trust away from the chocolate empire, the public outcry shut it down in record time, never allowing it to come to fruition so great was the fury. This means, for all intents and purposes, when you acquire shares of The Hershey Company, it’s probably the closest thing to going into a private operating business you’re going to find on the New York Stock Exchange.

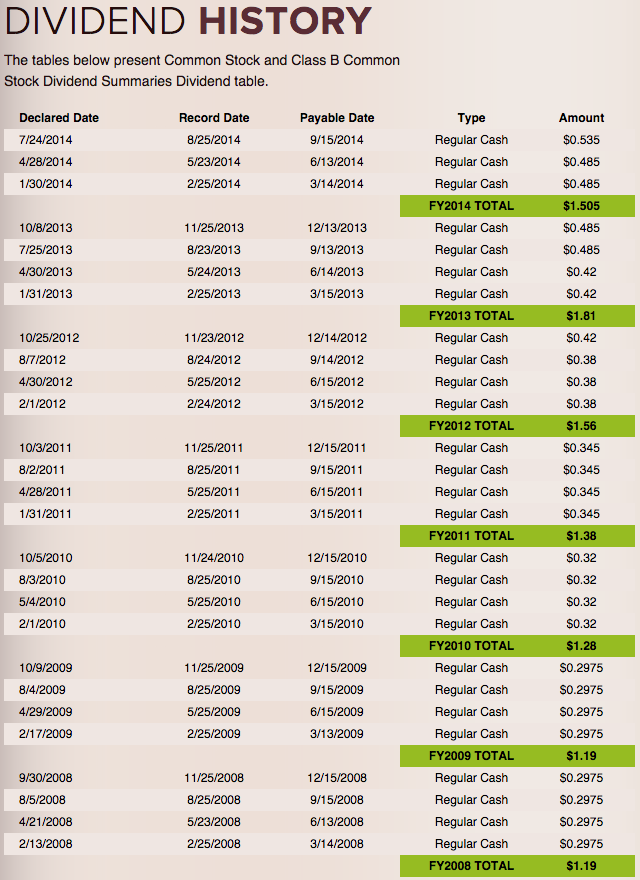

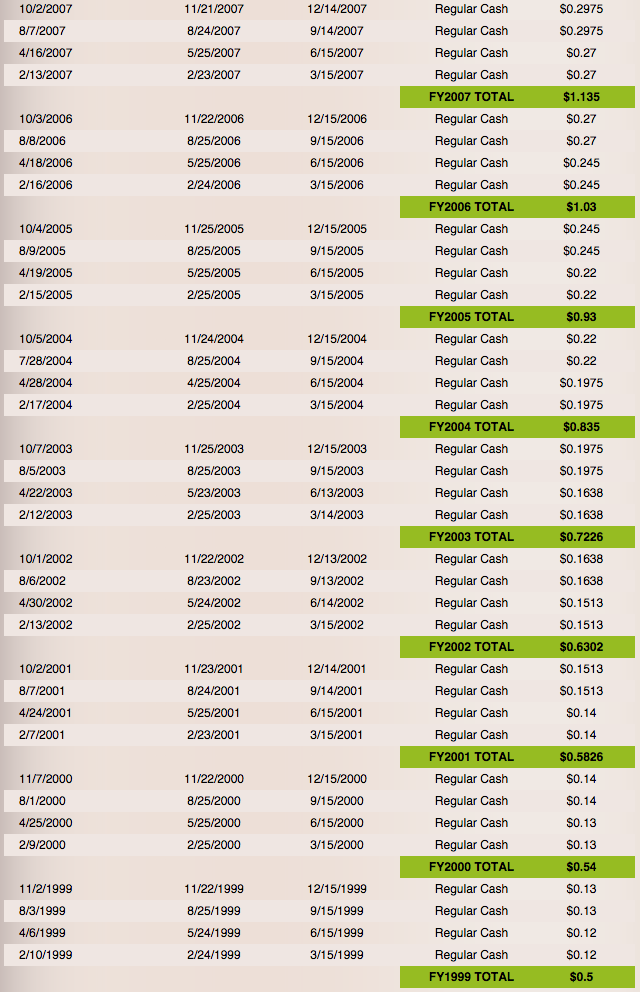

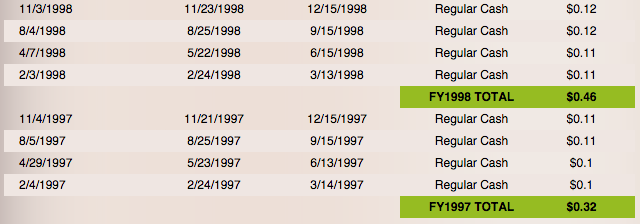

And about that dividend. It is sort of the physical record of all of these forces interacting with one another. The Hershey Company has paid a dividend every year since 1930. On October 3rd, 2014, the board of directors declared the 340th consecutive dividend on the common stock. Inflation, deflation, war, peace, Republican, Democrat, world war, cold war … doesn’t matter. People want chocolate and Hershey’s has between 6% and 8% of the North American market between its own brands, licensed Cadbury line, licensed Kit Kat line, and even high-end chocolate from subsidiaries such as Scharffen Berger. This is particularly noteworthy when you realize Hershey is predominately an American company. Only 20% or so of revenue comes from outside the United States. The firm has only recently cast its eyes to distant shores, working to acquire chocolate companies in India, China, and Mexico.

The dividend rate back in 1997 (the earliest shown on the company website, though the record is equally as impressive if we go further back in time) was $0.32 per share. By the end of this year, the rate will be $2.14 per share. That’s a 669% hike in 18 years for a person who owned 1 share of Hershey. To put it into perspective, a comparable increase in the labor market would be akin to someone earning $5.00 per hour back in 1997 now being paid $33.45 per hour today for the same work.

All of this is based upon the idea that an investor was able to live the lessons of men like John Bogle and Jeremy Siegel: You had to hold, passively, for a very long period of time, in the most cost effective, tax-efficient manner. No market timing. No attempt to day trade. You lived with the up years and the down years, not all of them pleasant. One illuminating example: During this period of market-beating compounding, Hershey went from a high of $67.40 in 2005 to a low of $30.30 in 2009. After nearly four years of patient waiting, you had watched your stock lose 55% of its value.

It didn’t matter. The money producing engine was intact as the underlying business was just fine. Nobody had come along and knocked Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, Kit Kats, Rollos, Hershey Bars, Cadbury bars, Jolly Ranchers, or Twizzlers off the top of the mountain. Every day, the corporate coffers roar with the torrent of incoming liquidity produced by millions of customers reaching for their favorite confectionary treat.

Accepting these fluctuations is part of the requirement of earning good long-term results. It is one of the reasons I tell individual investors to buy index funds (people who aren’t familiar with finance seem inherently happier with the illusion of a single, more stable security, than watching the individual components fluctuate much more wildly on a per component basis). If you buy even a handful of businesses in your life, you will see a 50%+ drop in even the best business in the world if you hold long enough to get the jaw-dropping compounding outcomes. There is no avoiding it. There is no escaping it. It’s part of the mechanics. If it causes you even the slightest bit of emotional distress, buy a short-term certificate of deposit, be satisfied with the outcome, and get what you deserve. There is no shame in it. You have to know what you can live with and, ultimately, it’s your life. Only you know the decisions that will make you happiest.