There has been a lot of talk over the past few days of corporate inversion. Corporate inversion happens when an American company changes its domicile to another country by merging with a foreign entity. Inversions have been occurring at a rapidly accelerating rate. Pfizer attempted one of the largest inversions in history with the AstraZeneca merger that ultimately fell through. AbbVie, one of our biggest medical companies is about to defect to Ireland through an inversion. Walgreens is seriously considering an inversion to move its business to Switzerland. Chiquita, the world’s largest banana empire, underwent an inversion and is now an Irish corporation.

Senators in Congress have gone so far as to say it is like “giving up on America” and frankly, that’s not entirely wrong. As shocking as it sounds, I have no problem with it, nor do I consider it immoral, because America deserves these defections. I love this country but Congress has implemented a tax regime on businesses that is the second most expensive in the world, putting a corporation headquartered here at staggering disadvantages to identical corporations headquartered in Europe and Asia. When it comes to business taxes, even the most socialistic countries in the world look like paradises compared to the abomination the United States maintains.

To help you understand what is going through the minds of some of the business owners who are leaving the country, let me walk you through a (simplified) fictional example that will paint a broad enough picture for you to get the gist of the debate.

A Simplified Illustration of How a Corporate Inversion Might Come About

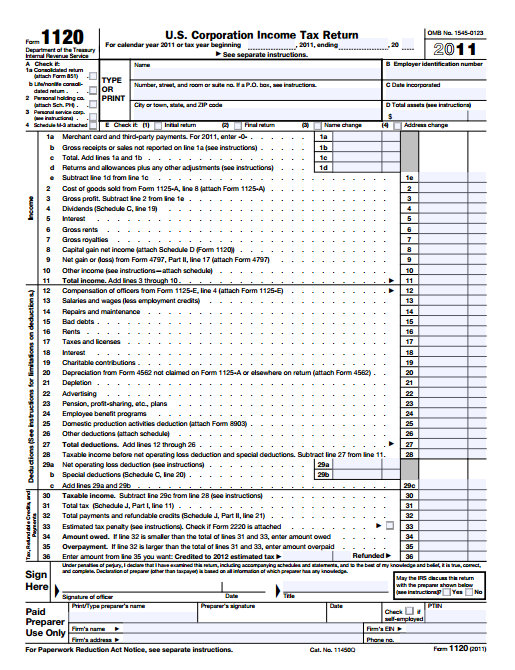

Imagine you love jam. You dream about jam. Jam is the only thing on your mind when you wake up in the morning and before you go to bed at night. Strawberry jam, blackberry jam, blueberry jam … it is your life. Jam is your calling. You started a jam company in the United States with a few thousand dollars in savings – we’ll call it Farmer Bob’s Jams & Jellies, Inc. – before ultimately becoming the largest jam manufacturer in the nation. The United States Government takes around 35% of your profits for taxes. While happy, you begin to feel like Alexander weeping at worlds yet unconquered. You set your eyes to distant shores.

You call your board of directors together and decide that you want to begin selling jam in England. “The British are going to love my jam!” you tell them. You convert some of your U.S. dollars into British pounds sterling. You and your lawyers get on a plane, go to England, and setup a new company. This totally new business is named Farmer Bob’s Jams & Jellies plc. It is domiciled in England. It is managed under English law. It is run by English citizens. It sells its products in English markets. It pays taxes to the Crown. Her Majesty’s government, however, only takes 21% of corporate profits, which is almost half of the rate charged in the United States.

Instead of holding the stock certificates directly, you have 100% of the stock of Farmer Bob’s Jams & Jellies plc owned by your American business, Farmer Bob’s James & Jellies, Inc. That way, you can manage everything centrally from back in the United States. Before long, your English business is making up a good chunk of your annual earnings. Your American company tallies up its profit and sends 35% to the IRS. Your British company tallies up its profit and sends 21% to the Crown.

Instead of holding the stock certificates directly, you have 100% of the stock of Farmer Bob’s Jams & Jellies plc owned by your American business, Farmer Bob’s James & Jellies, Inc. That way, you can manage everything centrally from back in the United States. Before long, your English business is making up a good chunk of your annual earnings. Your American company tallies up its profit and sends 35% to the IRS. Your British company tallies up its profit and sends 21% to the Crown.

One day you wake up and you think, “We have so much money in our British company, and it can’t grow any more, that I’d really like to bring it back to the United States! I could either reinvest it here to expand into peanut butter, creating more jobs at home for my fellow citizens, or even pay it out as a dividend so my stockholders can buy more cars, upgrade their houses, pick up a new watch, or go out to the movies. That’s a lot more economic activity which is good for the country and, as an American, I like that.”

You fly over to London to attend the board meeting of Farmer Bob’s Jams & Jellies plc and, along with the other directors, get ready to declare a dividend (which, of course, will go entirely to your American business since it is the sole stockholder). Suddenly, the secretary runs into the room with an emergency phone call. “Farmer Bob! It’s the CFO of the American parent company on the line.” You grab the phone and hear him scream, “Stop what you are doing! Don’t have the British company pay a dividend!”

[mainbodyad]Puzzled, you put him on speaker phone. He continues. “The United States Congress doesn’t like that Her Majesty only charges companies in her realm 21%. Since American businesses have to pay 35%, if you take a dividend out of the British firm and ship it back to the U.S., the IRS is going to force you to pay a 14% special tax to make up the difference for what you would have paid if you’d made the money here! Even though none of that profit was made in the United States, none of the assets are located in the United States, and the United States has nothing to do with the operations, Congress is going to confiscate the differential!”

“But,” you interject, “That makes no sense! I want to bring that money back to the United States for my fellow citizens to use it at home. I don’t want to keep it in England.”

“Sorry,” your CFO responds. “You can only avoid that tax if you refuse to bring the money back to the United States. You need to declare it indefinitely reinvested in your foreign subsidiary with no intention of ever bringing it back to America. That way, they can’t touch it.”

You grow angry. “This is idiotic! You mean, first, they want a cut of profit that wasn’t made in America and has nothing to do with America, next, they want to punish me for shipping it back to America so that it can be used to help our economy grow? They want me to keep the profits overseas? They want me to to build factories here in England instead of in my home state? You have to be kidding?!”

Your CFO doesn’t miss a beat. “That’s right. And worse, even after you pay that special tax, if you turn around and pay it out to our stockholders of the American business, they are going to charge them Federal, state, and in some cases, local taxes on top of it as we are one of the few countries that double taxes dividends! They’re going to end up taking at least half of everything, if not more.”

You begin fuming. “Almost no other advanced countries on Earth are this stupid. Our American business already pays a higher tax rate than practically everywhere else. Are you sure about this?”

“Yes, boss. Those are the rules. Economists, liberal and conservative alike, have been trying to change it for decades but politicians won’t listen to them because then the average person will think they are giving some sort of loophole to corporations.”

“Fine. Whatever.” You hang up the phone.

Years pass, and you, being the jam magnate that you are, find yourself repeating the past. Before long:

- You have a business setup in The Netherlands, where the government only charges you 25% for selling to Dutch customers.

- You have a business setup in Ireland, where the government charges you only 12.5% for selling to your Irish customers.

- You have a business setup in Taiwan, where the government charges you only 17% for selling to your Taiwanese customers.

- You have a business setup in Kuwait, where the government charges you only 15% for selling to your Kuwaiti customers.

- You have a business setup in Israel, where the government charges you only 26.5% for selling to your Israeli customers.

- You have a business setup in Finland, where the government charges you only 20% for selling to your Finnish customers.

- You have a business setup in Canada, where the government charges you only 26.5% for selling to your Canadian customers.

- You have a business setup in Denmark, where the government charges you only 24.5% for selling to your Danish customers.

- You have a business setup in Singapore, where the government charges you only 17% for selling to your Singaporean customers.

- You have a business setup in Sweden, where the government charges you only 22% for selling to your Swedish customers.

- You even have a business setup in Australia, where the government charges you 30% for selling to your Australian customers but allows you to give your shareholders a tax credit on dividends you pay them, effectively making the real rate much lower and in line with the rest of the world.

- Etc., etc., etc.

You’re a reasonable person so the result is the profit from each of these countries stays in its respective business. All that money you earn for all of those years … yeah, that’s not coming back to the United States. Instead, it will be reinvested in Finland and Kuwait; in Israel and Ireland; in The Netherlands and Australia. You’ll build new jam factories in Switzerland with your Swiss earnings and Canadian distribution centers in Canada with your Canadian profits. Even though you’re in disbelief at the rules – the U.S. is, again, practically the only place on planet Earth that has the arrogance to think it has a right to tax foreign earnings outside of its sovereign borders – you accept the situation begrudgingly until one day, you realize that half of your profits are coming from your non-U.S. businesses.

You may have started as an American business but that’s no longer really the case. Half of your workforce is non-American. Even if your stockholders are here, you can’t bring the money back to give them a big payout unless Congress declares a special repatriation holiday, which hasn’t happened in 13 or so years as the last one was included in the September 11th stimulus package.

You do a little math and realize that by moving the parent company to a foreign country – take your pick, Ireland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, whatever – you’ll be able to bring all of those foreign earnings back to the top level company and pay them out to your stockholders at much lower rates than you could if you remained an American corporation since practically no other nation is so arrogant and stupid as to insist it has a right to tax earnings that it had nothing to do with generating. Besides, it’s not like you are dodging any taxes because the IRS will still get its 35% on all sales generated from the United States market by the United States corporation through which you sell to customers in the United States. That doesn’t change. Even better, in a true Alice-in-Wonderland twist, it would be easier for you to take money from the foreign businesses and infuse it into the American operations, growing your U.S. business from afar. The only downside is the transaction would be taxable. The owners of your American stock would have to pay a capital gains tax, but in exchange, receive a stepped-up cost basis on the shares. For those who had been with you for a very long time, it could be a substantial hit if they held the stock outside of a tax shelter but, in the long-run, the savings should allow you to recoup it for them as profits end up higher than they would otherwise have been.

You announce your plan to move the parent business to Switzerland. Suddenly, politicians, including the President of the United States, are on television calling you unpatriotic and immoral, admonishing you for not paying your “fair share”; declaring you a “corporate deserter” even though, following the move, your American business will still be paying American taxes on its American profits.

The Treasury department tries to get new laws passed that will only allow you to leave the country if, after the move, 50% of your stockholders are non-Americans, apparently oblivious to the fact that this creates its own set of non-intended perverse incentives. After all, it’s not like they could stop you. It might be more work but if push came to shove, you could always shatter your empire into two, setting up a U.S.-only business and a separate global business, spinning off shares of the global business to your American stockholders.

Both Conservative and Liberal Economists – Practically All Of Whom Agree on a Solution – Continue To Be Ignored So Corporate Inversions Will Likely Continue

Meanwhile, liberal and conservative economists alike are ignored because their solution, while best for the country and the Treasury, makes it hard to bribe voters with promises that guarantee reelection. For decades, they’ve urged Congress to abolish the corporate tax rate entirely, close loopholes, minimize deductions, and tax individuals on all of their domestic income sources. That makes it much harder to hide money or lower your rate. No deductions to your alma mater or church; no deductions for your home mortgage interest or student loans. Clean, simple, direct – here’s what you made, here’s your tax rate, no industries are allowed to buy themselves special rules by lobbying Congress; $1 in profit from an oil company is taxed at the same rate as $1 in profit from your local plumbing business.

The next best solution is to at least make the American corporate tax system competitive with The Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Ireland, or Canada. Will it happen? Probably not until we’ve lost even more great enterprises. Even moderate attempts to match European nations on corporate taxation have proven to be a long-shot. Representative Dave Camp from Michigan has been trying to get a law passed that would change the U.S. corporate tax rate to 25% – which is still much higher than a lot of Europe, including quasi-socialist countries such as Sweden – but a huge improvement from the current rate, while closing loopholes and exempting 95% of foreign earnings from American taxes if they are paid up to the parent American company as a way to incentive businesses to bring their global profits back home to the USA; to build factories here, pay dividends here, hire more workers here.

[mainbodyad]Everyone, Republican and Democrat, should be behind this law as a short-term solution but it can be twisted to the non-economically literate to look like a giveaway to the rich, which means both sides of the aisle are afraid to touch it because it might lower their chance at re-election. It’s disgusting and, frankly, I think Europe deserves to steal our best businesses if we can’t get our act together. Congratulations Finland. Throw yourself a party Ireland. Have some more chocolate Switzerland. The stupidity of the American politician is resulting in you taking some of our more profitable firms.

Need proof? Go run your own case study numbers. A quick example: Last year, Coop, one of the largest retailers in Switzerland, earned $708,000,000 in operating income and paid $160,000,000 in taxes. That works out to 22.6%. Compare that to Williams-Sonoma, which earned $452,682,000 in operating income and paid $173,780,000 in taxes. That works out to 38.4%.

Nestle, a Swiss food company, earned $12,437,000,000 in operating income and paid $3,256,000,000 in taxes. That works out to 26.2%. (Even then, it is partially overstated as a big chunk of profits come from the United States and are subject to U.S. rates.) Compare that to J.M. Smucker, an American food company, which earned $849,700,000 in operating income and paid $284,500,000 in taxes. That works out to 33.5%

Switzerland has a balanced budget amendment, a strong currency, low-cost healthcare for its entire population, a world-class education system, and one of the highest standards of living anywhere, so the idea that competitive corporate tax rates are somehow incompatible with caring, comfortable societies is nonsensical. They aren’t wasting trillions of dollars ordering planes for the Pentagon that the Generals don’t want but the local representatives vote for, anyway, to create jobs in their district. It’s funny how much more you can do for society when things like that aren’t happening.

The longer the United States tries to put off corporate tax reform, and the richer the rest of the world gets, the more pain the average person will experience as our businesses defect. There is nothing in the universe, inscribed as some sort of divine law, that says the United States is blessed from on high and immune from the forces of free market and competition. If the U.S. offers a sub par product at a higher price, consumers (companies) will go elsewhere. This is not post-World War II when most of the rest of the globe is a pile of rubble. We are no longer the only game in town and it’s about time Washington realizes they aren’t entitled to anything.

They may think the defectors lack patriotism. I think they’re behaving like any American throughout history would. We are, after all, a nation born of those who were willing to risk everything to get on a boat for a new land. We opportunistically see a better country that treats us more fairly, waive goodbye, and take off for the promise land. That’s what we do. That’s who we are. While sad, I think it’s admirable. Until Congress fixes the problem, we get what we deserve.