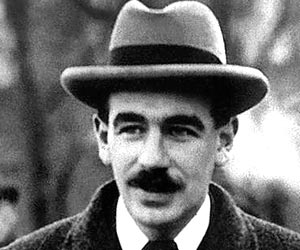

How John Maynard Keynes Beat the Stock Market by 8% Points Per Year Between 1921-1946

The Journal of Economic Perspectives: Vol. 27 No. 3 (Summer 2013) has a wonderful piece on the investment record of John Maynard Keynes, who managed to beat the market by an average of 8 percent per year from 1921 through 1946 by focusing on long-term, high quality dividend-paying stocks as well as smaller enterprises that had room to grow. When he died in his early sixties, Keynes had achieved the rank of one of the richest economists in history, amassing a fortune equal to $30,000,000 today.

He started out trying to be clever and making large macroeconomic bets, but after two near total wipe-outs, realized that the real money was in buying very good companies at dirt cheap prices then holding them. When he came to the startling realization that stocks had – in his words, an “intrinsic value”, different than the market price – a radical thought at the time – it changed how he began to put his own money to work. He slowly turned away from the currency trading, commodities speculation, and other distractions, collecting multiple streams of passive income as he turned his attention to accumulating a a world-class estate of rare books and artwork.

He started out trying to be clever and making large macroeconomic bets, but after two near total wipe-outs, realized that the real money was in buying very good companies at dirt cheap prices then holding them. When he came to the startling realization that stocks had – in his words, an “intrinsic value”, different than the market price – a radical thought at the time – it changed how he began to put his own money to work. He slowly turned away from the currency trading, commodities speculation, and other distractions, collecting multiple streams of passive income as he turned his attention to accumulating a a world-class estate of rare books and artwork.

David Chambers and Elroy Dimson went through and analyzed the complete trading records during those years Keynes was knocking it out of the park, detailing their findings in this publication. You can download the entire paper for free at the moment in PDF format from this link. It’s a good read, so you should add it to your case study files.

Keynes himself is most famous not for his brilliant capital allocation record, but for his economic theories. They stood in polar opposition to Friedrich Hayek, who had become almost entirely discredited in major academic circles by the end of his life as Keynesian approaches overtook the entire Western world. Keynes won the intellectual debate so completely that people outside of economics don’t even realize that he captured both sides of the political spectrum here in the United States; e.g., both President Reagan and President Obama are (in practice, anyway), die-hard Keynesians following almost identical economic policies. His victory was total, yet he remains hated by a very vocal minority who adhere to alternate schools of thought on the nature of the monetary supply and business cycles.