A Round-Trip Flight from California to Kentucky and Reading Middlemarch, a Study of Provincial Life by George Eliot

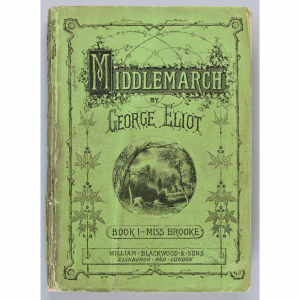

The Short Version: Do you love Victorian literature? If so, stop what you are doing right now and go buy a copy of a book called Middlemarch. If you want to read the same version I did, and which I discuss in this post, you can find it at Barnes & Noble. It is the cloth-bound reprint edition, published in 2011, through Penguin Classics.

The Long Version: The masterpiece Middlemarch, a Study of Provincial Life is considered by many literary critics and academics to be the greatest novel written in the history of the English language. A work of historical fiction, the story is set during the years 1829-1832 and follows the lives of the inhabitants of a fictional town, Middlemarch, as threads, both visible and invisible, weave the fate of their their homes, marriages, businesses, fortunes, happiness, and misery together.

The author, George Eliot, was a woman named Mary Ann Evans (she had decided to release her body of work under a masculine nom de plume to avoid having readers pre-judge her books, thus incorrectly assuming them to be little more than lighthearted romances, thus removing what she saw as an unfair disadvantage in the market). For decades, Eliot lived with her soulmate, a man named George Henry Lewes, after Lewes and his wife decided to live in an open marriage. This open marriage was necessitated by the fact that Lewes and his wife Agnes had three children of their own, but Agnes had also carried on a relationship with another man, Thorton Hunt, giving birth to four additional children of her lover. The birth certificate of one of the children that Agnes had with Thorton listed her husband, George, as the father, making him party to adultery. Thus, all were locked into their less-than-ideal state. The solution: George and Agnes agreed to an open marriage so they could each pursue their own happiness despite being bound by the law. George and Eliot fell in love, went on a honeymoon, and essentially lived as husband and wife for the rest of their days, Eliot even referring to herself as Marian Evans Lewes.

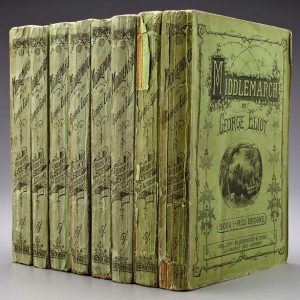

That matters a great deal to the history of Middlemarch because G.H. Lewes was Eliot’s agent. According to the introductory notes by Rosemary Ashton in the latest edition of the Penguin Classics hardback version of the text, George knew that Eliot’s work was going to be too long to fit within the standard three-volume format of the typical Victorian novel. He had an idea! He convinced John Blackwood, Eliot’s publisher, to adapt a model from Victor Hugo’s release of Les Misérables. They ultimately settled on releasing Middlemarch in “eight two-monthly parts at five shillings each, followed immediately by a complete edition in four volumes”, which came to market between December 1871 and December 1872. Thereafter, a single, consolidated, second edition was released that contained edits and improvements, including a re-write of the Finale based upon feedback Eliot had received. That second edition was the last, full version she herself would edit of Middlemarch and reprints of it are the one you are likely to encounter today if you pick up the book. It consists of over eight hundred pages, organized as 86 chapters plus a Finale.

How Middlemarch Came Into My Own Life

In the roughly 150 years that have passed since the words were penned, Middlemarch has stood the test of time in ways that other texts have not, still being every bit as relevant in the larger themes of life. Still, up until even a few weeks ago, I had no intention of reading the monumental work any time soon. My life and career have too many moving parts at the moment, and you know my rule about maintaining only one personal form of entertainment at a time as a technique to enforce discipline on our schedule and keep our productivity high. As such, there were a mountain of books, video games, and other projects that I expected to come before a 19th Century British masterpiece that wasn’t going anywhere.

The version of Middlemarch I read was a single tome, cloth bound in pink with white vignettes on the cover, published in 2011 by Penguin Classics and sold at a Barnes and Noble in Newport Beach, California.

Even those planned forms of entertainment usually fall behind my intentions because I love what I do professionally so much that many of my nights and weekends are spent diving into a new annual report or working out plans for our fiduciary wealth management company. The mail or our digital platforms almost always deliver a new stack of documents for me to read – everything from 10-K filings and proxy statements to merger agreements and economic data – so I find myself often putting in work days that go 15+ hours a day but that, to me, aren’t “work” at all in the sense that I find it enormously fulfilling and rewarding. My idea of a good time is thinking about mining demand versus supply for various metals over the next decade, looking at case shipments for beverage companies, and trying to discern hidden risks in the lending book of major commercial banks. The numbers that dance across a set of beautifully-formatted financial statements makes my heart sing. It’s not exhausting at all – if anything, it makes me feel more energetic and excited – to read trust instruments and build case studies of successes and mistakes made by great families attempting to transfer and protect their fortunes, knowing I might be able to use what I uncover for the advantage of not only my family, but the individuals and families that have entrusted their life savings to our firm. I find it an endless source of entertainment to examine complex systems and try to find ways to profit from the moving parts while improving society.

Thank goodness circumstances intervened and changed the order of things. I, and I suspect, those who rely on me, will be much better off because this book found its way into my hands. I will probably be thinking about it years from now as it forced a self-examination on certain topics, some of which I will discuss later in this post.

It began on Wednesday, July 24th, 2019. Aaron and I had spent much of the past week putting in extra hours, trying to accomplish as much as we could because we knew that the following day, Thursday, July 25th, 2019, we would be flying to Kentucky. Our plan was to visit the Blue Grass State for six days, during which time we would be staying with my brother and his family at their new home. The trip had several objectives, including:

- Spending time with them;

- Visiting the hospital where he had begun his anesthesiology residency;

- Meeting the newest addition to the Kennon family, a niece who had just been born; and

- Touring several of the Brown-Forman bourbon distilleries throughout the state, which had become increasingly important to Kennon-Green & Co. and its private clients.

On that Wednesday, the day prior to our departure, Aaron and I found ourselves on the lower level of the Barnes & Noble at Fashion Island in Newport Beach during our lunch break. He saw a copy of Middlemarch, picking it up as the pink and white cover caught his eye. I asked to see it when he was done, and, upon receiving it, flipped through the two-inch thick brick of pages. For reasons that neither of us can explain, I added it to the pile of books we purchased.

That evening, I was sitting in my office. Our apartment was clean. Our bags were packed. I knew I needed to go to bed soon so I didn’t want to commit to anything I couldn’t easily stop. On a whim, I opened the copy of Middlemarch we had acquired several hours prior. I intended to get a general feel for it, nothing more; to pass the moments before sleep and the flight across much of North America.

I read.

And I kept reading.

I decided to take the book with me to the airport since I couldn’t exactly do any sensitive work in public – we deal with people’s most private financial affairs, which requires discretion and I didn’t want to study any other businesses except the bourbon distilleries that I knew we were going to visit as I wanted to keep my entire attention on them for the trip.

Sitting in the John Wayne airport in Orange County, I read as we waited for our flight.

On the flight from Southern California to Atlanta, Georgia, I read.

Sitting in the airport in Atlanta, Georgia, waiting for our connecting flight to Lexington, Kentucky, I read.

On the flight from Atlanta, Georgia to Lexington, Kentucky, I read.

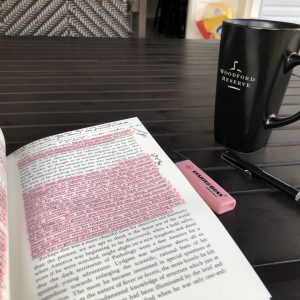

When I cracked open the book the night before, running my hands on the pages and taking in the first words, I did not intend to embark on a literary journey that will stay with me for the rest of my life but that is exactly what happened. As pages were traversed, Eliot built a world, every bit as rich and interesting as Pride and Prejudice or Downton Abbey. It wasn’t long before my pen and highlighter were by my side as I marked up the text, using it as a journal of sorts; a scratch book to reflect my thoughts and feelings on how the lessons contained within the narrative might help me, my family, and our clients both personally and professionally. I have never, in all of my reading, encountered an author who wrote characters as fully developed and human as those found in Middlemarch. The folly and glory of men and women is here, both resplendent and contemptible. Yes, like any large drama, it took hundreds of pages for the cast of characters to come into view as their backstories were revealed. The reward was worth it. By its conclusion, I felt this large network of people, intertwined in numerous ways both great and small, were almost real; that I knew them as surely as I did my friends and neighbors. She came as close as any author can to giving souls to her creations.

Of particular importance given my personal and professional love of finance and investing: sorting out the exact names, and per annum incomes produced by the real estate holdings, of each of the mentioned landed gentry so I could approximate their purchasing power and relative influence. (On a side note, it truly is amazing the extent to which land, and rental income, dominated politics, personal relationships, and class during the height of the British empire. Do people really understand what the Law of Property Act 1925 did in terms of modifying the division and allocation of power and resources on the other side of the Atlantic? A strong argument can be made that it was one of the most important, influential reforms of the past century. I know folks bemoan the decline of large estates and the romantic dreams they conjure but the idea that a “dead hand” can rule the lives of the living so many generations after it has passed seems fundamentally immoral, therefore I view the abolition of entail as a net good. I think historical experience is convincing enough that it’s safe to say had the United States not abolished this real estate ownership mechanism at the time of the Revolutionary War, we’d essentially have a hereditary aristocracy right now. People concerned about inequality would pray for the situation in which we find ourselves relative to what it might have been had our ancestors not been willing to prohibit this mechanism for holding title. On the other hand, there has been at least some reflection in certain academic circles that this abolition of property restriction in the United States may have had a second-order and third-order effect in that it could have prolonged the slave trade by essentially forcing wealthy Confederate families to follow a labor management business model rather than a real estate / rental business model. I have not, yet, studied that particular hypothesis, so I have no present opinion as to whether I think it is plausible but it is worth mentioning as a demonstration that, sometimes, consequences are not always as direct as one might be tempted to believe.)

During our visit, I kept reading in moments when I could spare an hour or two here or there, usually sitting outside on a screened-in porch early in the morning with a cup of coffee or during afternoons when my niece and nephew watched Disney’s Moana. I wish I could share more pictures but for privacy reasons, I can’t. I think I’m going to have to create photo books for the family, instead, and have them published now that the blog can no longer serve that function due to its larger size (and the world seeming much less stable than it did a few years ago).

On the flight back, from Lexington, Kentucky to Detroit, Michigan, I read.

On the flight from Detroit, Michigan to Orange County, California, I read.

Why Reading Middlemarch Was So Valuable to Me

One of the chief moral goods that can come from literature, or any art, is that by examining the folly of others, a wise person can hope to avoid that folly in himself or his own household. Likewise, by reflecting on the virtue and good in others, we can hope to behave with more virtue and goodness. On that front, Middlemarch did not disappoint. There is plenty of righteousness and sin to abound as every theme imaginable is present. The characters who occupy this place and this time are brought forth and developed, one by one, not only through the revelation of his or her innermost thoughts and desires but outward actions towards others, serving as both a mirror through which we can examine ourselves and a lens through which we can better view the world. You find yourself thinking about responsibility of love and duty, especially when they may conflict, personal financial management and bankruptcy, the difference between law and morality, the nature of proper restitution for an action honorable men would condemn but for which legislative statute has no answer, honor, family, domestic happiness, particularly in marriage, prejudice and bigotry, pride, religious fanaticism, and much, much more. Many times, I would be enraptured in the midst of a drama with one character or another and realize that Eliot was simply illustrating, in parable form, a lesson I’ve written about over the decades.

A person who reads this book, and who is familiar with the power of mental models and the historical context in which it exists, can extract enormous value from it. Even someone who had no interest in literature proper, but solely wanted to improve his or her understanding of people and the world, could benefit. What are businesses except complex systems meant to source, develop, and distribute goods and services to end consumers while generating a reasonable risk-adjusted return on capital to owners? Every step along that chain – vendors, suppliers, employees, customers – is dominated by people. People are influenced by a wide range of motivations, hopes, dreams, biases … better understanding people, and how they make decisions, can be one of the strongest competitive advantages imaginable. Figure out what people want; their motivations. Figure out what they fear. Figure out what gives them hope. Then, try to help them and make their life better. If you do that – if you approach it from the perspective of serving others and wanting what is best for them – you can go further than most people could ever hope. I don’t care if you own a small tire shop or are a high-powered attorney in New York City or Los Angeles.

In my reading of Middlemarch, several things stood out to me.

There is an intense debate surrounding a character who opts to avoid the standard professional practice at that time of doctors earning their living by selling pharmaceuticals rather than charging for their services. This causes him to be hated by other physicians and they believe that through his attempt to behave better, and avoid the inextricable conflict of interest in such a practice, he is disparaging their own medical practices. Those who have read Poor Charlie’s Almanack might immediately recognize how this relates, both directly and indirectly, to concepts such as the Serpico mental model; how corruption, once it becomes widespread within an institution, geographic area, or profession seeks its own preservation as people come to depend on the ill-gotten gains.

There are models of different types of marriages and how being yoked to someone who overspends can destroy even the best plans of the hardest working people. The single most important decision most people will make in their lives is who they marry (or if they get married at all); finding someone who shares the same goals and objectives as you, who wants the same lifestyle and priorities, then putting him or her above everyone else as you order your lives together pursuing those shared dreams.

There are arguments about the appropriate level of capital expenditures for maintaining the real estate that is leased to tenant farmers, revealing various approaches that still arise in business relationships to this day.

In fact, the core issues arising throughout the pages of the text are complexities that humans are still dealing with today. Conditions have changed, human nature has not. For example, many in the town are distrustful of outsiders and immigrants, refusing to reconcile their own feelings with their professed religious beliefs as evidenced by this conversation between Selinda Plymdale and Harriet Bulstrode:

[Mrs Plymdale speaking] ‘…I should say I was not fond of strangers coming into a town.’

‘I don’t know, Selinda,’ said Mrs Bulstrode, with a little emphasis in her turn. ‘Mr Bulstrode was a stranger here at one time. Abraham and Moses were strangers in the land, and we are told to entertain strangers. And especially,’ she added, after a slight pause, ‘when they are unexceptionable.’

‘I was not speaking in a religious sense, Harriet. I spoke as a mother.’

Of course, the reader is supposed to question: how can there be a difference? If moral imperatives can be set aside like a jacket that needs to be removed when the temperature gets a little too warm, they aren’t principles, they are philosophical drag; costumes with which to adorn yourself to make yourself feel better about the type of person you are.

Middlemarch Helped Me in Thinking About the Line Between Showing Grace and Being a Doormat

On many topics, I’ve watched this same hypocrisy play out around me over the past few years with a sense of wonder, horror, and grief. Between the years of 2015 and 2019, it’s caused me an unspeakable amount of suffering to realize that many of the people whom I formerly believed were on some level good are, in fact, morally bankrupt, intellectually lazy, and have near zero integrity; Pharisees who are convinced they will hear, “Well done, thy good and faithful servant,” despite living in a way that makes “Depart from me for I never knew you,” more appropriate. What’s worse, the people who are guilty of it have absolutely no sense of self-reflection whatsoever and are blind to their own wickedness and depravity. They are like the casual bigot who in past generations said, “I support civil rights” because they didn’t feel hatred in their heart toward disadvantaged groups yet they still maintained their golf memberships at social clubs prohibiting black, Jewish, or Hispanic members, or bought homes in white-only neighborhoods, essentially enabling those who did and thus making them accomplices.

This experience has caused me to accept that if a Hitler or Stalin were to ever rise, Munger was right: a substantial majority of the people around me won’t, actually, hold to their principles but, instead, adapt their world view to their base prejudices. I was naive to think otherwise. I actually believed in the lessons I was taught in Sunday school and civics class; how mankind is inherently endowed with dignity and intrinsic worth that must be respected. It turns out the people around me didn’t. They wanted a social club and palliative because, at their root, they were simply afraid. Afraid of anything different. Afraid of change. But most of all, afraid of death. To them, all of their cherished proclamations and scripture were little more than an existential Xanax blind to the needs of their fellow citizens and deaf to the cries demanding justice.

Still, the Finale of Middlemarch, and in particular, the two paragraphs at the end of the journey – which must be read after the completion of the entirety of the text or else you will cheat yourself of their impact and both the tragedy and beauty of them – are among the best passages I’ve ever encountered among the millions upon millions of words I’ve read because they provide an answer to that depressing fact. They will stay with me, echoing from time to time as I bring about my plans and choose a course of action. They cause me to recall the words of one of our mentors, a college professor, who once said in a commencement speech about doing good – and I’m paraphrasing the sentiment – “Now, let our work be as the Buddhist monk, forgotten”. The actions we take in life, when they positively influence others, are like a bell ringing out into the universe, the vibrations changing the course of things in ways we can never anticipate nor measure, and that may never be credited to us. It is still important to do them, even if we are utterly abandoned by history and esteem. Do good because it is good, not because you want the praise. Do good because it may help others who never knew you existed.

I also find myself reflecting on a conversion in Chapter 72; something that, when I first read it, stopped me on the spot because of how powerful it is. During a conversation over dinner, some of the more influential citizens of Middlemarch are discussing a character (whom I won’t mention for fear of spoiling the plot) who has, up until this point, behaved well towards them but whom, by association with another character and the unfortunate timing of an action about which he had no knowledge, has since fallen into scandal despite no direct evidence being found against him; the mere suspicion of guilt being enough to destroy his world, both socially and professionally. Dorothea, one of the main characters, refuses to accept that a potentially innocent man who had shown no signs of dishonesty – or even a guilty man who wished to repent – could be discarded so easily by his friends. The conversation:

‘Oh, how cruel!’ said Dorothea, clasping her hands. ‘And would you not like to be the one person who believed in that man’s innocence, if the rest of the world belied him? Besides, there is a man’s character beforehand to speak for him.’

‘But, my dear [Dorothea]’, said Mr Farebrother, smiling gently at her ardour, ‘character is not cut in marble – it is not something solid and unalterable. It is something living and changing, and may become diseased as our bodies do.’

‘Then it may be rescued and healed,’ said Dorothea.

This is not a woman who will throw her friends, or even enemies, away if she believes they are being treated unjustly. Righteousness is enough of an answer for its own sake. In the same conversation, she poses a question that I keep coming back to in my deepest, innermost thoughts: “What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult to each other?”

This had such an impact on me because it reflects a private dialogue with which I’ve struggled for the past few years.

On one hand, there is a part of my soul that sometimes tends towards Old Testament Judge. In my own life, I have standards that are so high for my personal conduct – an internal scorecard – that I can often be exacting in my measurement and evaluation of my fellow man. There is no great secret, no source of shame, that could ever be used against me in any business deal or personal relationship due to the fact that in my conduct with my fellow man, I’ve done everything, at all times, honestly and in a way that I would be comfortable having it appear on the front page of a newspaper if reported by a good reporter with integrity, who had noble intentions to communicate the facts as they occurred rather than to cast a positive or negative light on them. I don’t understand what is so difficult about doing the right thing or, if you realize you’ve done something wrong upon reflection, apologizing for it.

On the other hand, when I do try to be understanding, I don’t know where the line between showing grace, and being a doormat, is.

Building upon some of my earlier comments, I can say this with certainty: someday, if and when I do open up and write about my experiences over the past decade without reservation and in total candor, this will make a lot more sense. Suffice it to say, I still don’t have an answer. I fear I’ve fallen too far on the side of showing grace but if we are to err, isn’t that the direction we should prefer?

Middlemarch Demonstrates the Value of Liberal Arts Education

Reading Middlemarch made me once again think about the importance of work that lasts beyond yourself. Here I am, on the other side of the planet and nearly 150 years later from when this woman, George Eliot, wrote these words and, yet, she has changed things for me in the way a stone thrown into a pond irrevocably alters the future of that pond in ways that are immeasurable.

In other words, the value of a book like Middlemarch is not merely the enjoyment you get out of reading it. It’s really about the hours you spend, staring off into the distance, and reflecting upon – thinking about – how these things apply to your own life, your own relationships, your own community, your own moral and ethical values. There are several instances of property disposition through inheritance in the book that get to matters of justice. As someone who, present known factors considered and assuming Aaron and I have an ordinary life expectancy, will someday be responsible for the disposition of an enormously large estate, this isn’t merely academic to me. The decisions we make, as husband and husband, will change the course of lives and marriages, occupations and charities.

Going further, reading the book has made me realize something I hesitate to say – something I discussed with Aaron during a break from the office two days ago when we took a walk before returning to our desks. It is related to our past discussions of economic distributions, cultural capital, etc., and has to do with the almost insurmountable obstacles to reducing inequality in the United States now that we have moved into a more meritocracy-based knowledge economy. Like a horrifying spectre that I knew was there but didn’t want to turn to acknowledge, the thought kept entering my mind as I traversed chapter after chapter. That thought: this book is a perfect example of the class and wealth divide in present day America because if we were to hand a copy to every man and woman over the age of 18 years old, I would bet an enormous sum of money that 85 or more out of every 100 of our fellow citizens would not have the reading level to comprehend the text in a comfortable way that allowed the lessons to flow and be assimilated. Perhaps the number is even higher. To them, Middlemarch would not be an experience of joy and self-reflection, but of exhaustion and effort. Worse, many of the references would go completely over their head, losing their effectiveness. This is a failure as a civilization. The liberal arts should not be reserved merely for the rich or privileged.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not talking about liking Middlemarch. Plenty of brilliant people with high reading levels may not like Victorian literature due to the dense prose. Personally, I adore it because I could spend all day reading about hypothetical property dispositions and land rental return rates mixed in with love stories and community dramas unfolding. No, I’m talking about being able to read it. Physically able to pick up the book and it be as natural to understand as having a conversation with someone over a cup of coffee.

Let me give you an example.

For the past two thousand years, anyone with a classical education, or knowledge of history – which includes nearly all of the top elite members of society – is aware of one world-altering event that changed the course of human civilization. It’s as much a part of the invisible background of existing for those with advantages as reflexively using the subjunctive mood (which, hand-to-God, Middlemarch had a brief passage referencing it as the sign of the well-educated when, in Chapter 24, it described Mrs Garth as a housewife whose station in life might not have revealed the quality of her education) or investing in shares of stock. That event: Julius Caesar defied the order of the Roman Senate to disband his army at the end of his governorship and not cross the Rubicon river, which served as one of the northern boundaries of Italy. He did it anyway, supposedly uttering, “alea iacta est”, or “the die is cast” as his soldiers walked across the shallow waters, setting into motion the Roman Civil War, his eventual dictatorship, and the rise of Rome’s Imperial Era. Had that not occurred, probabilities dictate that none of us would be here right now – different people would have lived and died, different nations arisen … it was one of the major events in the story of mankind with reverberations that can never be undone and still circle the planet to this moment. If you want to learn more about it, here is a good introduction from National Geographic.

As a result, the phrase “crossing the Rubicon” has long been a short-hand way of acknowledging that a person is taking an action that, once done, marks the point of no return. It’s everywhere. It’s in newspaper articles, magazines, literature. It’s even in music. For example, Elton John and Leon Russell worked it into one of their songs:

Knowing what the Rubicon is, and why it matters, is a socioeconomic marker. It provides a clue to who you are; your background, your education, your reading habits. In isolation, it might not mean much but taken together, it is one of the numerous threads that form a complete tapestry in revealing where exactly one falls on the hierarchy of society. Even if you weren’t aware of it at, say, 20 or 30 years old, if you have managed to get yourself into a higher-earning profession or continued your acquisition of knowledge, you will by the time you are 40 or 50 or 70 because you’ll encounter it at several points. It’s hard to avoid.

These socioeconomic markers develop for a reason. They are also a way in which power perpetuates itself as those with capital tend to want to be around others like themselves.

There is a passage that George Eliot works into Middlemarch that uses this event, and the powerful history surrounding it with all of its political and emotional implications. A certain character in the book, whose name I have redacted to avoid spoilers, has been so devastated by a misunderstanding that has occurred, and which has destroyed his chance at ever being happy with a specific woman whom he has loved deeply, that he considers fleeing. He had befriended the wife of a friend who, in her vanity and arrogance, assumed that he loved her and threw herself at him; something he found abhorrent not only because of his love for the aforementioned different woman but because he wouldn’t betray his friend in such a way, bringing disrepute upon himself. Honor matters to him. Self-respect matters to him. During the moments the unfaithful wife-of-a-friend throws herself at him, and he is responding, the woman he really loves walks into the room and sees it, destroying his reputation in her eyes and causing her to rush out in a panic. He is stunned. He screams at the unfaithful wife, cutting her with his words, because he is now caught in a trap that his honor won’t let him escape. On one hand, he can’t rush after the woman he loves and tell her the truth – that this wife-of-a-friend has thrown herself at him – thus ruining her reputation to save himself, because she (the woman he really loves) would consider it a less-than-noble act. On the other hand, he can’t stand the fact that she now believes him to be a dishonest adulterer in love with another woman.

He flees on a stage coach to a nearby town, Riverston. He was tempted to go further, disappearing without a trace to avoid facing either his friend (the husband) or the woman he loves. He collects himself. He decides that he must return to the town, say goodbye, and then quit Middlemarch forever. No happiness can be found for him in the place he wanted to call home. Eliot writes:

Thus he did nothing more decided than taking the Riverston coach. He came back again by it while it was still daylight, having made up his mind that he must go to [the home where all of this occurred to call on his friend, the husband] that evening. The Rubicon, we know, was a very insignificant stream to look at; its significance lay entirely in certain invisible conditions. [The man] felt as if he were forced to cross his small boundary ditch, and what he saw beyond it was not empire, but discontented subjection. (emphasis added)

Without an understanding of that historical allusion, this passage might slip under the radar but it’s an example of how much of a genius George Eliot was. She knew how to write, in a single sentence or two, a passage that tied in a broader understanding of events to have them carry far more weight than the word count alone could manage. Someone seeing this scene – a man riding a stage coach back to Middlemarch – would be forgiven for not understanding the implications of what were about to occur as it didn’t look impressive or out of the ordinary. Like the Rubicon, “its significance lay entirely in certain invisible conditions”. Once crossed, once this course of action taken, his life would never be the same. He was committing to something that would reverberate forever, unable to take it back should he desire.

For me, this is one of the reasons I can’t recommend the book to most people because it’s just going to end up a doorstop. That causes me emotional and intellectual pain because any time you encounter something that is useful, it’s natural to want to share it; to bring it into the lives of others and say, “Look! This thing can be a valuable tool!” but knowing that they might look at you and never be able to appreciate it or understand it because we, as a society, have failed in our commitment to education. Again, I would almost bet money you could sort public school districts into various distributions and the top, maybe, 1% to 10% are going to have a decent number of students who, by grade twelve will understand that reference. Most others won’t. The shared language and knowledge base isn’t there.

It makes me feel the same way I first did when a long-time friend of ours – someone Aaron and I have known since we were teenagers and who is now a school teacher – recounted the struggles of one of her friends. This friend-of-a-friend had gone to university intending to enter public education because she was passionate about teaching. She finally got her dream job as a Freshman literature at a high school in Missouri. Only, she quickly found herself crying during the evenings because she realized that most of the kids in the student body were so far below reading level that they were functionally illiterate; that she couldn’t share great literary works like this, and the impact they can have on lives, due to the fact her students were quite literally not capable of understanding it and should have been held back many, many grades. When she, rightly, began failing students, the administration admonished her, telling her she was going to hurt their funding by reducing their performance statistics (or some comparable incentive-driven nonsense, the details of which I can no longer recall). She spent the year simply surviving, in some cases resorting to picture books, before quitting the teaching profession altogether as she couldn’t stand the practice of “social promotion”.

Thank God for my teachers. Thank God for the public library. Thank God for Reading Rainbow and Sesame Street.

What about the kids who don’t have that?

I don’t have a solution. The vocabulary and reading comprehension gap is already enormous between lower class children and the children of middle class and upper class families by the time they enter elementary school. To go back to an earlier sentiment, “the die is cast” at that point. Changes become more difficult. Attempted solutions, such as busing children in from poorer areas to more affluent areas, have been major failures historically. They don’t work. Even more than that, if you add too many lower class children to a good school district, there comes a point at which the families that made the district good in the first place pull out because they don’t want the problems those poorer children bring with them to harm their own kids. This is a structural issue. Education reform and income inequality cannot be tackled in any meaningful, lasting way without addressing the breakdown of the family household unit in the bottom portion of society. One of my frustrations is that a lot of people don’t want to go down this route for fear of hurting someone’s feelings and making them feel inferior so they do more lasting harm, opting for politeness at the expense of actually solving the issue.

Unfortunately, I see the same sort of misguided efforts now applied in the college and university arena; somehow trying to make them so accessible under the misguided notion that it is simply the piece of paper – the degree itself – that promises a better life. It doesn’t. A degree is like fiat currency. Alone, it has no value – it’s just paper and ink – but it can be enormously valuable due to the knowledge backing it. If a dictator demands a university give his son or daughter an engineering degree, the son of daughter does not magically have the ability to do actual engineering work. It’s the skills that count.

I’m wandering down different intellectual corridors now … but those of you who have read long works that stay with you after you’ve put the book down know this feeling. There is so much you are trying to sort through, to organize in your mind, and gain closure. I think the reason I enjoyed Middlemarch so much also comes down to the fact that a good portion of the plot revolves around wills, trusts, and inheritance law, real estate interests, private income, and the nature of human relationships in light of what Charlie Munger referred to as the Super Power of Incentive mental model; how even the most powerful of men and women can find themselves bending in ways they would find abhorrent had they not been seduced by their own self-interest, provided that seduction remains unspoken so they can plausibly deny it to their own conscience, thus evading analysis for fear of being found wanting. There were several examples of the horns and halo mental model. There were conflicts around love and marriage, which I’ve already mentioned – an area around which my own life experience causes me to feel immense compassion. In that regard, I, at one point, found myself caught up in plotting how to legally and ethically circumvent 19th century British property law – what solution would I have structured had I been their advisor? – convinced there must be some way to defeat a given instrument that threatened to stand in the way of a certain man and woman joining together for a lifetime of happiness as I found myself rooting for their union. I ultimately settled on a few general techniques that gave me several hours of enjoyment, working out the details in what might very well someday be useful exercises for our asset management firm should we encounter a modern-day problem that, while perhaps having different lyrics, at least rhymes or shares the same music.

The bottom line: If you have any interest in this sort of literary work, read Middlemarch. In my own case, as I mentioned earlier, my journey began on the evening of Wednesday, July 24th, 2019. It concluded two mornings ago, Tuesday, August 6th, 2019, at 8:24 a.m., Pacific time, when I completed the final pages sitting at the dining room table in Newport Beach, where I had been since around 5:45 a.m. A good chunk of that was read on airplanes flying back and forth across the United States the week we did the bourbon distillery tours. There is no “right way” to go about reading this book – some folks take six months to get through it, enjoying it in stops and starts – as you need to find your own pace and preference.

It’s also worth noting that sometimes you have to be in the right place and time for a book to speak to you. I’m not sure what lessons I would have gotten out of this at 18 years old had it been assigned reading; perhaps none, maybe even a dislike for it. What I know is that right now, at this time, and in this place, it had tremendous value, allowing me to reflect upon, and process, things that had been on my mind in recent years. That means that even if this book isn’t for you right now, it may be, someday. Keep it in the back of your mental file cabinet and revisit it in the future.

George Eliot wrote seven novels. It is now a goal of mine to read the other six in the coming years, maybe arranging them around holidays or business travel.