Thanksgiving Dinner at Fleming’s in Newport Beach

Happy Thanksgiving to all of you! I hope you and your family had a wonderful holiday!

This year was a bit different for us. Aaron and I made a decision awhile ago that we were going to do something we haven’t done since we were college students in our early twenties: skip making Thanksgiving dinner dishes from scratch and, instead, go out to a restaurant. It felt strange since we cook so much but it was the right call and an easy decision for two reasons. First, my mornings and evenings have been consumed with putting the final touches on the templates that we are about to roll out for private client statements at Kennon-Green & Co. – not only checking the statement logic structure itself so it displays what we want it to display where we want it to display it, but the commentary that will go along with it describing why we believe certain reports are important and what we think private clients should be looking for in them – and second, his mom is coming to visit us for a week so both he and I want to get as much as we can on our task list done so we can actually leave our desks (at least for the duration of her visit until it’s back to normal) at the end of the work day. Our time is too valuable right now and cooking ourselves would have required almost two full days of preparation and cleanup.

Several of the restaurants in Newport Beach were offering Thanksgiving dinner menus. We ultimately settled on Fleming’s steakhouse because it looked the most traditional, it was only a few blocks away from our new place so we could get back to work after we had eaten, and whenever we would go to the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meetings in Omaha, it was always our preferred steakhouse so we have fond memories of it. As expected, it was great. For our starter course, we had a few Artisan bread rolls and chopped salads made of walnuts, tomato, cucumber, root vegetables, parmesan, and honey-lime vinaigrette. For my main course, I had a mixed herb-roasted turkey breast (dark meat) with savory turkey gravy, fresh cranberry, and an orange and cinnamon sauce. It came with housemade sage and brioche bread stuffing and green beans and onions on the side. Aaron’s meal was identical with the exception of the meat. He ordered the sliced beef tenderloin with cabernet demi glace. They also brought us two dishes for us to share as additional sides – a butter-mashed sweet potato and a Yukon gold mashed potato. For dessert, we both opted for a pumpkin cheesecake with pumpkin spice and gingersnap crust. I had a cup of black coffee with mine.

The whole thing was only $117.00 for the food + $9.07 in tax + the tip we left. That was a huge bargain considering what we would have spent in ingredients and the opportunity cost of our time had we opted to cook at home as per our usual routine.

Access to these kinds of regular dining options is still strange to me. I mean, those of you who have been around awhile might remember a few years ago when I made a butternut squash soup with cinnamon sugar croutons. Yesterday evening, we wanted to grab something quick to eat and ended up going into a local grocery store. They had butternut squash soup for sale for, I can’t remember, maybe $6.99 for an 8 ounce bowl? It was good, too. Like, maybe 85% as good as the homemade-from-scratch version. (The biggest difference seemed to be that they added some sort of chili pepper to the soup itself, giving it this nice after burn. I prefer the richer, creamier, more traditional version but it was a nice take on it. I could see how someone would like that version.) Not to mention, the meat and fish section at the grocery stores is out of this world compared to what I was used to in the Midwest.

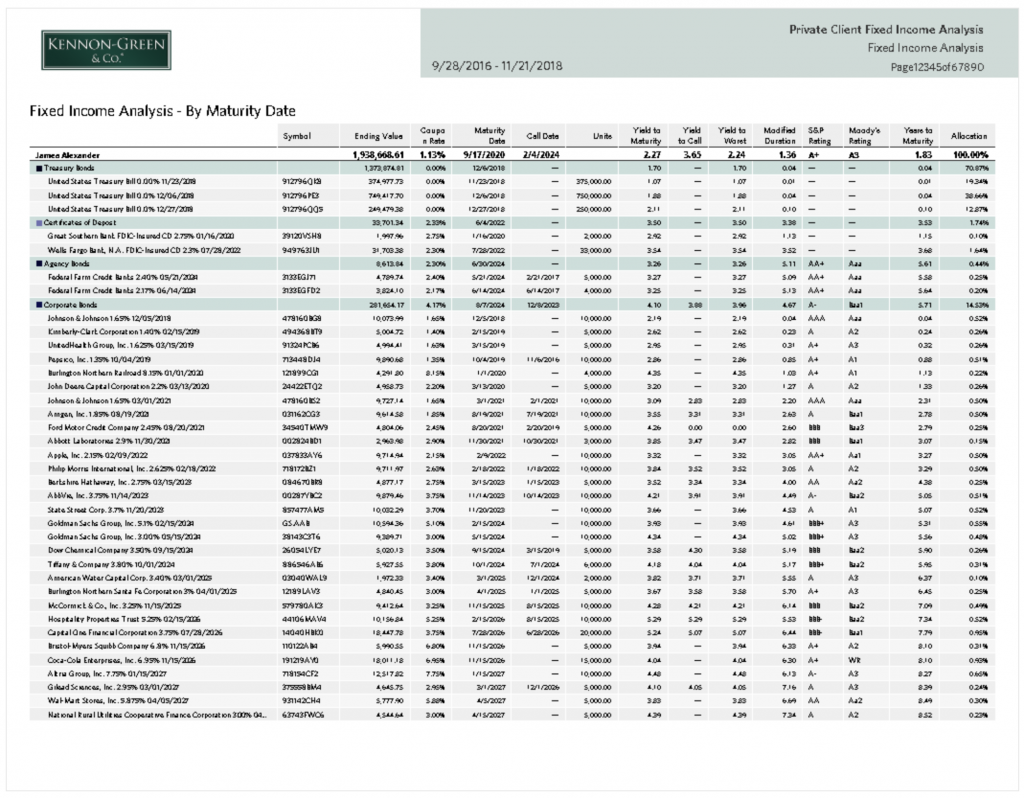

Anyway, I’m going to get back to work but I wanted to wish you all a Happy Thanksgiving! My night is going to be filled with trying to write an explanation for a fixed income analysis report. Fixed income is one of those strange areas that people who don’t deal with it regularly can get caught up on how the reported accounting differs from economic reality, particularly when glancing at a cash income projection report. For example, during periods in which interest rates are rising, the coupon yield on fixed-income securities bought in the secondary market are going to be lower, perhaps even much lower, than the yield-to-maturity or yield-to-call. This means that both historical income, and projected future income, will be lower than the actual total return on the bond by the time maturity arrives as a result of the portion of return that is collected through that discount to par reaching par value by maturity. This same phenomenon is present when a person seeks to generate higher returns on surplus cash by purchasing short-term U.S. Treasury bills, which are issued at a discount to their maturity value. These assets, which are considered the safest asset in the world as they are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Government with all of its taxing and military power, have a 0.00% coupon yield and appear as if they generate no projected income on the reports. On the flip side, when interest rates have declined, and we purchase fixed-income securities in the secondary market at premiums to par value, the coupon yield will exceed, sometimes materially, the yield-to-maturity or yield-to-call. This will require the bond premium over par to be written off over time, reducing the value of the bond, to offset the higher coupon rate. Relatedly, the projected income shown on the reports will be higher than the real, economic income the owner is entitled to enjoy.

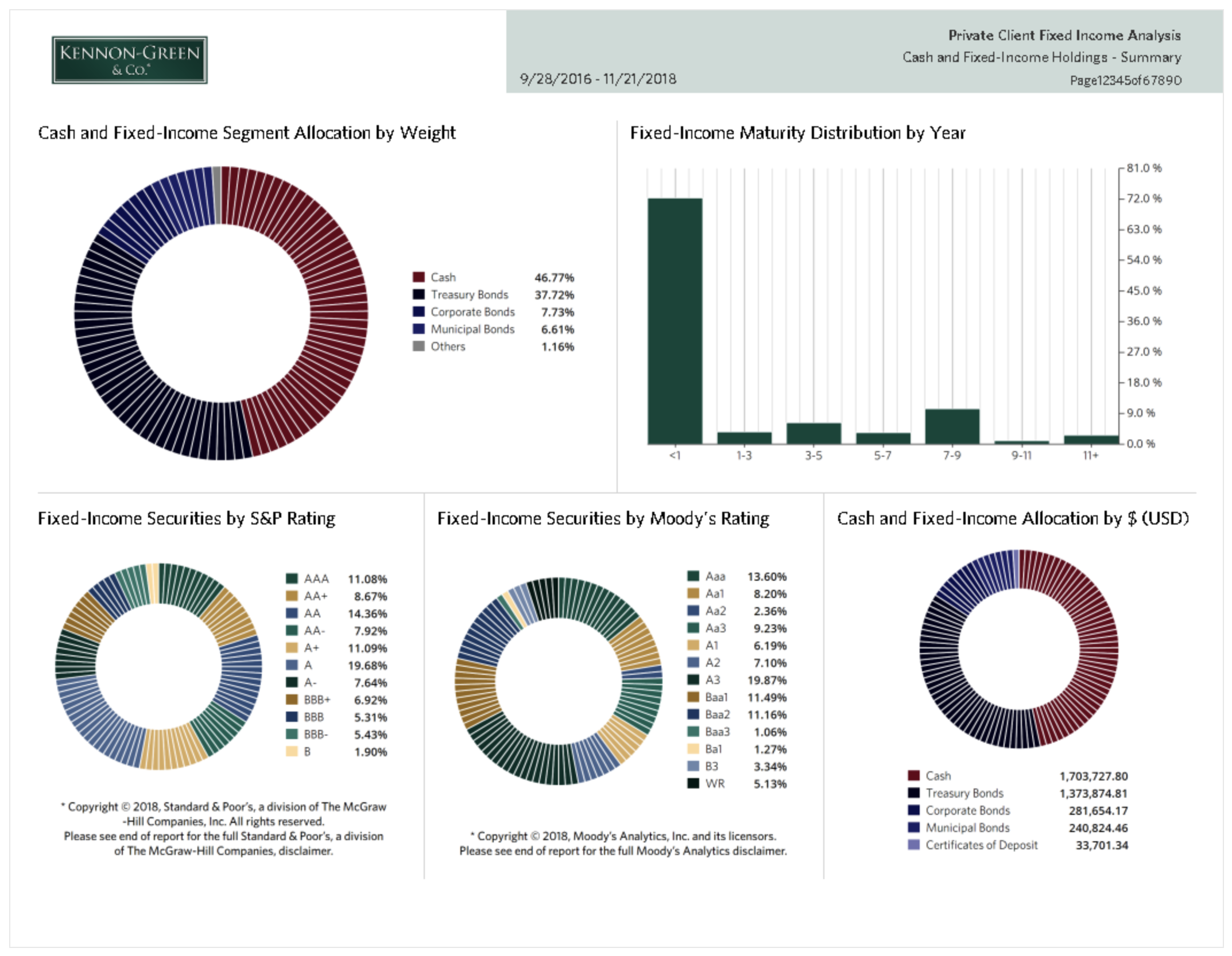

It’s … I have to write in a way that is accessible and doesn’t overwhelm people. All those years writing as the Investing for Beginners guide should come in handy. To get this kickstarted, though, I’ll probably use that description in the introduction, or something close to it, and another description near the fixed income analysis page itself. Or maybe, just to get these initial versions published and in clients’ hands, I’ll get the reports out in the coming days and weeks and then write a “Guide to Your Private Client Statement” book like some of the private banks have done. So many of these things I only have to do once then they scale tremendously but I don’t want to outsource this. I don’t want to just pick some off-the-shelf report that everybody else has, I want people to see the data the way we see it – the things we think matter when we are managing capital. The latter might be a better choice because I’d like to write guides that explain what concepts such as duration mean in the context of fixed-income investments (the short answer: it’s a measure of interest rate sensitivity). I want the S&P and Moody’s ratings. I want the CUSIP. I want multiple tables arranged by things like maturity date and/or portfolio weight. I want someone with a few million dollars in capital to have the same sorts of insight into their money as a large institution. That’s the goal. I might have to take the Microsoft approach and release Version 1.0 then keep hacking away at it, making it better and better with time. I’m not going to delay these, again. We are so close.

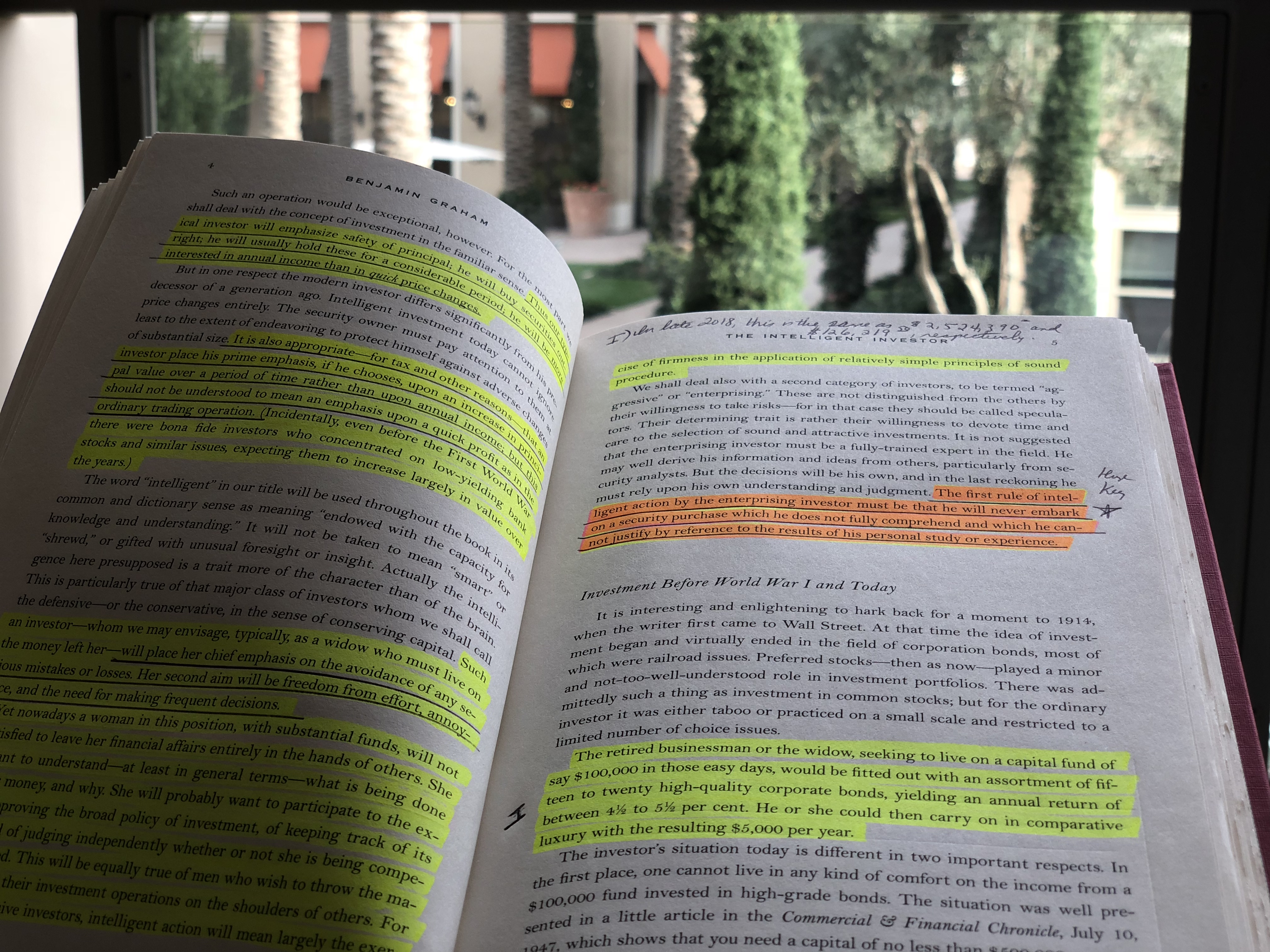

That is my life these days. To keep myself connected, and grounded, to the spirit of what I’m trying to do, I’ve been re-reading some of Benjamin Graham’s old works lately. While the mechanics of his operations have changed significantly in the nearly 70 years since the original Intelligent Investor was published in 1949, the philosophy is timeless. Time and time again, Graham looked at the effective substance of a thing over its surface form, eschewing investment “rules” that everybody else preached because he thought they fell apart under the scrutiny of logical analysis.

While it is impossible to pick a favorite passage, I’m struck by how, so many years after I first read it, the five paragraphs between pages 40 and 42 (reference footnotes omitted) still ring true:

While it is impossible to pick a favorite passage, I’m struck by how, so many years after I first read it, the five paragraphs between pages 40 and 42 (reference footnotes omitted) still ring true:

As we see it, the investor-stockholder occupies a middle or compromise position between true ownership of part of a business and mere ownership of a stock certificate. He undoubtedly lacks some important powers of control which inhere in individual or partnership-group possession of the enterprise. But in this respect he is in a position no different from that of a minority holder of shares in a private business, when such holder is not part of the controlling group. But he also has what is in truth a tremendous advantage over such a minority holder, in that he can sell his own shares any time he wants to at their quoted market price.

But note one important fact: The true investor scarcely ever has to sell his shares, and at all other times he is free to disregard the current price quotation. He need pay attention to it and act upon it only to the extent that it suits his book, and no more. Thus the investor who permits himself to be stampeded or unduly worried by unjustified market declines in his holdings is perversely transforming his basic advantage into a basic disadvantage. That man would be better off if his stocks had no market quotation at all, for he would then be spared the mental anguish caused him by other persons’ mistakes of judgement.

Incidentally, a widespread situation of this kind actually existed during the dark days of the 1931-1933 depression. There was then a psychological advantage in owning business interests which had no quoted market value. For example, people who owned first mortgages on real estate which continued to pay interest were able to tell themselves that their investments had kept their full value, there being no market quotations to indicate otherwise. On the other hand, many listed corporation bonds of even better quality and greater underlying strength suffered severe shrinkages in their quoted markets, thus making their owners believe they were growing distinctly poorer. In reality the owners were better off with the listed securities, despite the low prices of these. For if they had wanted to, or were compelled to, they could at least have sold the issues – possibly to exchange them for even better bargains. Or they could just as logically have ignored the market’s action as temporary and basically meaningless. But it is self-deception to tell yourself that you have suffered no shrinkage in value merely because your securities have no quoted market at all.

Returning to the A. & P. stockholder in 1938, we assert that as long as he held on to his shares he suffered no loss in their price decline beyond his own judgment may have told him was occasioned by a shrinkage in their underlying or intrinsic value. If no such shrinkage had occurred, he had a right to expect that in due course the market quotation would return to its cost price or better – as in fact it did the following year. In this respect his position was the same as if he had owned an interest in a private business with no quoted market for its shares. For in that case, too, he might or might not have been justified in mentally lopping off part of the cost of his holdings because of the impact of the 1938 recession – depending on what had happened to his company.

Critics of the value approach to stock investment argue that listed common stocks cannot properly be regarded or appraised in the same way as an interest in a similar private enterprise, because the presence of an organized security market “injects into equity ownership the new and extremely important attribute of liquidity.” But what this liquidity really means is, first, that the investor has the benefit of the stock market’s daily and changing appraisal of his holdings, for whatever that appraisal may be worth, and, second, that the investor is able to increase or decrease his investment at the market’s daily figure – if he chooses. Thus the existence of a quoted market gives the investor certain options which he does not have if his security is unquoted. But it does not impose the current quotation on an investor who prefers to take his idea of value from some other source.

Those words are life changing to those who have the wisdom to understand what they mean. In them resides several of the secrets to achieving, and just as importantly, to maintaining, financial independence. Alone, they are not enough but they are pillars holding up a well-constructed fortress.