Walter Schloss Value Investing Strategy

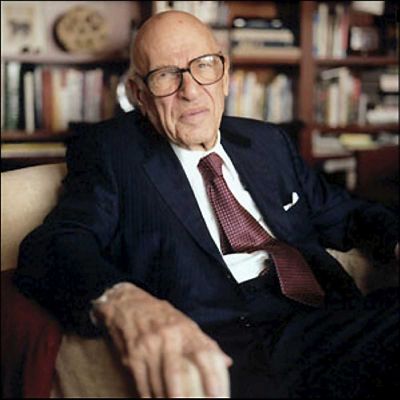

Walter Schloss, a legendary value investor who learned directly from Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, never graduated from college and was hired as a runner on Wall Street in 1934, at the age of 18. Schloss enrolled in the New York Stock Exchange Institute, where he took courses from Benjamin Graham on how to value businesses, find value stocks, and manage money.

Using the lessons he learned there, Schloss launched his own value investing fund in 1955, with a starting balance of $100,000, eventually growing to manage money for as many as 92 investors.

For more than 50 years, he earned a 15.3% compounded annual rate of return, turning a $10,000 initial investment into $12,344,268, far outstripping the 10% return offered by the S&P 500 during the same period, which would have resulted in only $1,173,909.

Putting Together a Walter Schloss Value Investing Portfolio

Unlike most professional money managers, Walter Schloss remained faithful to his value investing principles, refusing to deviate from the same formula he learned from Benjamin Graham, even in spite of his friendship with and exposure to Warren Buffett.

Working from a small desk in the offices of Tweedy, Browne & Company, the brokerage firm that handled both Graham’s trades and bought Warren Buffett his shares of Berkshire Hathaway, Schloss sought to acquire as many companies trading at a 1/3 net working capital as possible. Schloss believed that he would come out ahead due to the benefits of widespread diversification, even though many of the companies he owned were considered unattractive by most of Wall Street due to some underlying problem in the business or with a key supplier.

Working from a small desk in the offices of Tweedy, Browne & Company, the brokerage firm that handled both Graham’s trades and bought Warren Buffett his shares of Berkshire Hathaway, Schloss sought to acquire as many companies trading at a 1/3 net working capital as possible. Schloss believed that he would come out ahead due to the benefits of widespread diversification, even though many of the companies he owned were considered unattractive by most of Wall Street due to some underlying problem in the business or with a key supplier.

Walter Schloss relied on very little more than a copy of the Value Line Investment Survey. As was often the case with most value investing funds, he didn’t charge a management fee but instead took 25% of profits, ensuring he only made money when his partners did. He never hired any employees and worked alone. By the time he wrapped up his partnership, annual profits had reached $19,000,000 with expenses of only $11,000!

Here are some of the things Walter Schloss looked for in a value investing portfolio:

- Companies backed by real assets with little or no debt, providing a source of value if the company liquidates or gets sold

- A discount to book value of at least 20%, preferably more, with the book value consisting of cash, fixed assets, and other tangibles

- A good dividend yield. This shows the company’s earnings were real (you can’t fake cash that’s paid out to stockholders)

- Managements that own a substantial amount of the company’s stock so that their interests are aligned with the other shareholders

- Honest management that doesn’t overpay itself. Even if a company is good, if management is dodgy, don’t invest.

- If you can’t find good value investing positions, park your money in cash.

- Consider buying after a dividend cut if you think the business will survive. It will almost always sell off more than it should, providing patient value investors an opportunity to get unbeatable prices.

Walter Schloss also made some other value investing trades that were not without risk. He shorted Yahoo and Amazon before the dot-com crash, according to Fortune magazine, and made a tremendous amount of money for his partners.

Walter Schloss On Why Value Investing Works

Walter Schloss was not, by his own admission, a terribly intelligent man compared to the average genius working at a hedge fund. Yet, he managed to crush their performance without a stressful life, working only from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. five days a week. This was due, in his estimation, to the success of a value investing strategy that allowed him to impose discipline on his buy and sell decisions, turning investing into a science rather than an art. Combined with his self-control in keeping expenses tightly regulated, spending virtually no money on frivolities or waste, and compounding will do the heavy lifting.