One of the additions I have been considering adding to the KRIP is The Clorox Company. However, it appears somewhat overvalued right now, offering a lower earnings yield and slower sales growth compared to the S&P 500 if you view the index itself as a single stock, which doesn’t bode well on a relative basis. That can be fixed by a reduction in market value of 10% to 20%; if you are patient long enough, you almost always get your price.

So I wait. In the meantime, I thought we could talk about the story, finances, returns on capital, dividend history, and simplicity of the Clorox business and how it combines to create one of the few near-perfect enterprises in the world (despite a scary period a couple of decades back when the then-management went on an acquisition spree that destroyed shareholder value and was ultimately reversed). It is the perfect sort of stock for the KRIP portfolio. It shows up to work, generates cash, distributes almost all of it in share repurchases and cash dividends, and goes unnoticed most of the time.

Had I wanted to run a corporation instead of own my own companies and invest, I would have gone to work at a company like Clorox, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, or Johnson & Johnson with an eye on the executive suite and been one of those guys who ended up collecting more in dividends from my shares of the firm than I earned in salary and bonus. I have a soft spot for these types of wealth generators that produce value from products that make life better for people and raise standards of living.

A Brief History of the Clorox Company Adapted from the Company’s 100 Year Celebration Literature

In 1913, five investors each contributed $100.00 in cash to a new enterprise they called the Electro-Alkaline Company. The original shareholders included Edward Hughes, a wood and charcoal salesman, Charles Husband, an accounting bookkeeper, William Hussey, a miner, Archibald Taft, a banker, and Rufus Myers, a lawyer. One year later, in 1914, 750 shares of stock were issued to raise $75,000 in start-up capital ($1,727,843 in 2012 terms). The purpose of the business was to create the first significant bleach factory in the United States to supply industrial and government concerns, such as municipal water plants, with a super-concentrated version of bleach (boasting 21% sodium hypochlorite). The flagship product was called Clorox, coming from a combination of ingredients chlorine and sodium hydroxide. Giant jugs were loaded on horse-drawn carriages and delivered throughout the San Francisco and Oakland areas.

Sales for the full fiscal year 1914 were $7,996 (that is $184,211 in 2012 terms). Unfortunately, the company struggled, despite making an excellent product, because it had no marketing expertise. On the verge of a catastrophic collapse that would have relegated the start-up to the history books, William and Annie Murray, a Scottish-American couple who owned a local grocery store, took action. They had invested much of their early savings in the company and couldn’t afford to see it fail. William was hired as the general manager of the firm, reorganized the production process, and worked with banks to arrange a more favorable capitalization structure for the balance sheet, while Annie began insisting on the creation of a less concentrated version of the bleach that could be sold to household consumers. She handed out 15 ounce samples at the grocery store and word of mouth soon spread about the benefits of cleaning with the amazing chemical mixture.

Sales for the full fiscal year 1914 were $7,996 (that is $184,211 in 2012 terms). Unfortunately, the company struggled, despite making an excellent product, because it had no marketing expertise. On the verge of a catastrophic collapse that would have relegated the start-up to the history books, William and Annie Murray, a Scottish-American couple who owned a local grocery store, took action. They had invested much of their early savings in the company and couldn’t afford to see it fail. William was hired as the general manager of the firm, reorganized the production process, and worked with banks to arrange a more favorable capitalization structure for the balance sheet, while Annie began insisting on the creation of a less concentrated version of the bleach that could be sold to household consumers. She handed out 15 ounce samples at the grocery store and word of mouth soon spread about the benefits of cleaning with the amazing chemical mixture.

In 1922, Electro-Alkaline Company changed its name to reflect the money maker, calling itself the Clorox Chemical Corporation. Then, in 1928, the business reorganized itself as a Delaware Corporation and went public on the San Francisco Stock Exchange by issuing 200,000 shares of common stock. The firm grew by printing instructions for bleach, still an unknown product at the time, in a wide range of languages so new American citizens from France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Russia, and elsewhere understood the appeal.

Unheard of at the time, Clorox was known as a liberal company that would even hire not only women, but single mothers, decades before the rest of the nation would even consider such actions acceptable. The Great Depression came and went without a single layoff. Later, during World War II, when supplies were unavailable due to shortages, Clorox competitors reduced the concentration of cleaning agent in their product. Clorox refused to compromise on quality and sold smaller packages, instead, making the name synonymous with quality.

Unheard of at the time, Clorox was known as a liberal company that would even hire not only women, but single mothers, decades before the rest of the nation would even consider such actions acceptable. The Great Depression came and went without a single layoff. Later, during World War II, when supplies were unavailable due to shortages, Clorox competitors reduced the concentration of cleaning agent in their product. Clorox refused to compromise on quality and sold smaller packages, instead, making the name synonymous with quality.

For another two decades, the firm continued humming along, churning out huge profits for shareholders with a small workforce of only 300 to 400 employees. Then, in 1957, Procter & Gamble bought the company, renaming it The Clorox Company and making it a wholly owned subsidiary.

[mainbodyad]An antitrust suit was filed and, years later, the United States Supreme Court handed down a ruling supporting the Federal Trade Commission that forced Procter & Gamble to divest the business. In 1968, the firm began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the name P&G had given it, The Clorox Company.

For the next fifty years, various brands were added to the stable. Dividends rose most years, profits continued to climb, share count was reduced due to buybacks, and stockholders made a tremendous amount of money from the stable, boring, brilliantly awesome business of selling bleach to American, and now global, families. Those who reinvested their dividends did even better. It would have been entirely possible to become a multi-millionaire off an investment in the storied bleach maker.

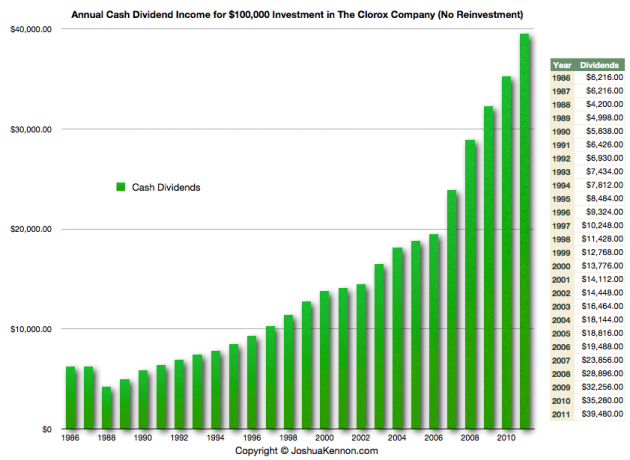

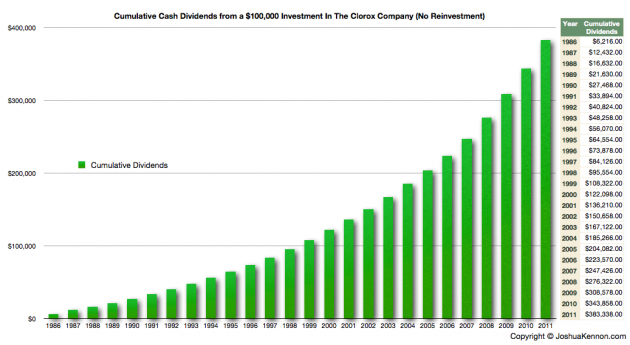

A 26 Year Look at The Clorox Company Investment Returns

Imagine it is 1986. The year is somewhat arbitrary in that it is the furthest back I could go without doing a lot of digging. You have $100,000 sitting in the bank. You aren’t sure what to do with it. You decide to acquire 2,100 shares of The Clorox Company, take the stock certificates, and put them in a vault. The cash dividend checks are mailed to your home, where you promptly open them, put them in the bank, and spend the money. You decide to ignore the stock market, not caring about the fluctuations, and focusing solely on the profit the business generates, and how much profit it sends you in the mail. As long as the figures are going up at a rate higher than inflation, you figure everything should work out fine.

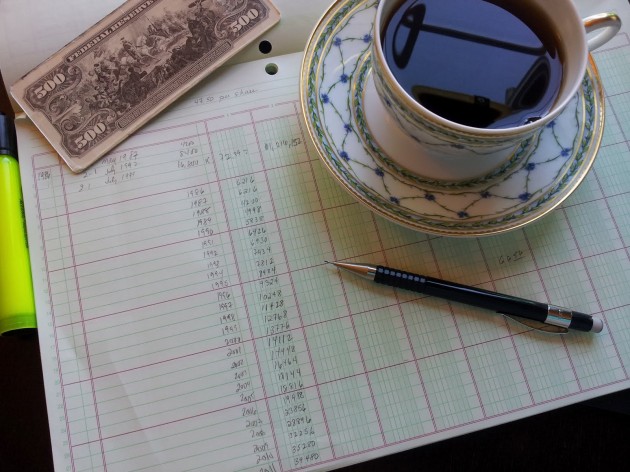

How much money would you have, assuming you did not reinvest any those dividends? I broke out a hand spreadsheet, a mechanical pencil, and a list of historical dividend distributions to find the answer.

I went back and calculated the historical dividends for a $100,000 in The Clorox Company from 1986-2011

In the first year, 1986, you would have collected $6,216 in cash dividends. By the final year, in 2011, you would be receiving checks for $39,480 in cash dividends.

Over the full 26 year period, assuming no dividend reinvestment, The Clorox Company would have mailed you $383,338 in cash dividends on your $100,000. Plus, due to stock splits, you would now be sitting on 16,800 shares, not the 2,100 shares you started with in the beginning. The stock closed 2011 at $66.56 per share, giving your 16,800 shares a market value of $1,118,208.

Bottom line: Without reinvesting your dividends, 26 years ago, you wrote a check for $100,000. Your company, Clorox, mailed you $383,338 in cash dividends and your shares now have a market value of $1,118,208. Thus, you turned your $100,000 into $1,501,546 over a quarter of a century. Your compound annual growth rate was approximately 11.45%. How much of that you got to keep depends on whether you held your shares in a tax sheltered account or in a plain vanilla brokerage account, as well as your personal tax bracket.

[mainbodyad]For making a single decision, reading an annual report for an hour every year, and doing nothing but sitting back and collecting checks, that is one heck of a deal.

If the company could repeat that same performance over the next 25 years, your original $100,000 investment would have grown to $22,570,462 from a combination of cash dividends and share price appreciation. That is the power of compounding. That is the longest stretch of time most people can bank on achieving because 50+/- years is what I consider a single “investing lifetime” … that is, someone who starts at 25 years old would be 75 years old at the end of the program.

Most Investors In The Clorox Company Didn’t Enjoy Those Rich Returns Because They Sold Their Stock

Looking at turnover in Clorox shares, the firm, like most other publicly traded companies, doesn’t have very many stockholders who buy and hold for decades. Why didn’t investors enjoy these returns? Take a look at the stock chart for The Clorox Company over the time frame we’ve been discussing.

Looking at a 26-year stock chart of The Clorox Company, there are a lot of 30% to 50% drops during which time an investor would have seen the quoted value of their Clorox shares hit extraordinarily hard. In the end, it just didn’t matter. Only a fool sold his or her shares out of fear. The Clorox Company, makers of Clorox bleach, Glad trash bags, Tilex bathroom cleaner, Liquid-Plumr, Pine-Sol, S.O.S. scrubbing pads, K.C. Masterpiece sauces, Brita water filters, and Kingsford charcoal, minted money for its owners.

In the late 1990’s to early 2000’s, an investor in The Clorox Company would have watched roughly half of the value of the shares disappear right in front of them. But at the same time, profits and dividends were still rising. The investor who focused on cashing the checks and monitoring the results knocked it out of the park. The investor who panicked or got impatient missed out on significant wealth creation.

The Recipe for Good Investment Returns

This is one of the reasons that I think, psychologically, the average person is going to enjoy vastly superior results if he or she:

- Finds a great business with a strong competitive position and high returns on capital

- Makes a significant investment when the company is reasonably valued

- Puts the stock certificates in a vault or uses the direct registration system

- Dividend reinvestment plans are a real option for those who don’t want to value businesses frequently. A company like Clorox charges $0 to plow dividends back into additional shares in the business and only $5 if you want to write a check and mail it in to buy more shares with new out-of-pocket cash

- Collects cash dividends year after year

- Waits for opportunities to buy more shares when the valuation gets attractive, always ready to write another check

- Judges the “success” of the investment solely by his or her share of the underlying profits (total shares x earnings per share – the tax paid if distributed) and the cash dividends.

That recipe, over 20, 30, and 40+ years, can produce tremendous results, especially if there are at least 10 stocks in the portfolio. People don’t have the patience for it. A school teacher in Wisconsin could get obscenely rich by retirement doing nothing but running a few financial calculations and letting time to the work. This is one of the reasons I tell you that the first $100,000, or even $500,000, is the most important. I don’t care if you have to starve yourself and clip coupons to get your hands on your initial capital, you need money that generates money for you, preferably tax-free. It gets much easier after that because your assets start throwing off checks for $3,000 here and $25,000 there.

What does the future hold for Clorox shareholders? Who knows. There appears to be some risk of commoditization in the categories in which the firm does business. That is the risk part of investing. The next part is the price. The stock doesn’t look particularly cheap at present levels. For someone with a 25 to 50 year horizon, that may not matter as much. For example, if a friend of mine won the lottery and approached me to put together a portfolio of 30 stocks that paid dividends of more than 3% and would not be sold for 25 years, Clorox would be on the list because the premium to intrinsic value wouldn’t matter as much given that is relatively small relative to the time and income parameters. For my long-term holdings, it is one of those things that is on the shopping list but will only get bought when the price falls to a level at or below my calculation of fair value.