This is a great question about habits of successful people and families …

I read your post about energy savings and saw a comment from from someone named Melissa K. You had responded to a reader from overseas and shifted your language and units to their syntax, talking in square meters and degrees Celsius rather square feet and degrees Fahrenheit. She said, “You often talk about the knowledge that the affluent pass onto their children and this post is a great example. You pretty effortlessly switch dialects to fit your European audience. I recently was debating school English curricula and argued that we need an earlier emphasis on audience for kids.”

It seems obvious now that it is spelled out in front of me, which makes me want to ask. What other behaviors do you think differ from successful people and ordinary families? Not things like how a 401(k) works but behavioral patterns?

Leron P.

One of the big ones seems to be the ability to constantly be moving toward whatever it is they have purposed in their heart. You see this passed on to children of the successful more often than not, modeled after a lifetime of observing it. To be more specific about it:

- Clearly identifying what it is they want to achieve

- Taking specific, coordinated, planned, targeted action toward arriving at the end goal

- Spotting or creating opportunities that might not be apparent to help them get there more quickly

- Putting their own long-term interest ahead of their short-term wants, ego, or emotions

Successful people, to borrow a phrase, are like heat seeking missiles. It may sometimes seem like I am unfocused or going from thing to thing if you read the blog, but you cannot imagine the level of obsession I bring to a project when it gets my attention. There have been hints of it but I doubt many people realize how non-normative it is if they aren’t like that themselves or know someone who is. Almost everyone in my life who is successful in his or her field has some derivation on this theme (not all – there are a few who somehow woke up to find themselves in the executive suite but, generally, it’s true). Stumbling into success is possible but it seems to be the exception. Rather, most have been been perfecting, obsessing, and driving toward their particular end goal, in their particular field, and will put everything else aside to achieve it. If you haven’t seen the documentary film, Indie Game: The Movie, watch it. That’s what I mean. Martha Stewart was the same way with lifestyle improvement. Sam Walton was the same way with retail. Warren Buffett was the same way with investing. Tiger Woods was the same way with golf.

[mainbodyad]Even if you never become a household name, if you are obsessively focused on an area that offers high potential rewards, and you have the natural ability to leverage that focus (you’re not going to become the greatest basketball player of all time if you are 4’11” tall and have no hand-eye coordination), you can end up light years ahead of everyone else. A real estate investor in the middle of Iowa might very well amass an eight-figure property portfolio by the end of his or her lifetime simply because of 30, 40, 50+ years of studying values, waiting for opportunities, grabbing them when they manifest themselves, or crafting them out of thin air. He or she wakes up every day looking, searching, thinking up ways to collect more rents. Very few people do that. They wake up and just go on autopilot, getting closer to death without any real agenda. That’s fine if it makes you happy but it seems as if few people actively choose that life. Most appear to fall into it and don’t know how to escape. Successful people always make it a point to actively choose.

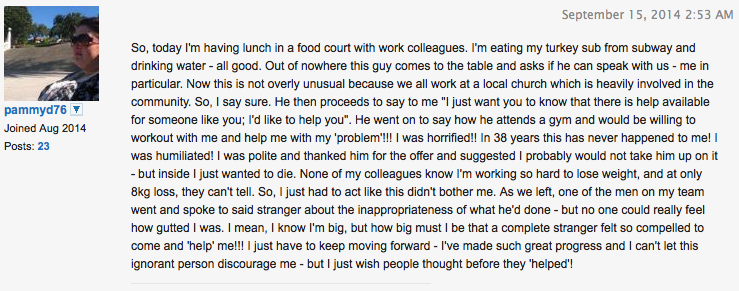

You can tell whether or not someone has this disposition almost immediately if you are in proximity to them. I’ll give you a real world example of someone who doesn’t to make the contrast starker. Earlier this morning, I came across a post on an online message board devoted to healthy living. The author of the post wrote about an experience that “horrified” her to the point “inside [she] just wanted to die.” Here is the story she left on one of the most popular public fitness forums in the world, in her own words:

This is a textbook example of how not to react or feel if you want to be successful in life. Should the man have approached her? Probably not. But were I the woman in this situation, my brain would have rapidly gone through a couple of checklists like this:

- Am I morbidly obese? Yes. Check.

- Do I want to lose weight? Yes. Check.

- Does this person seem genuinely helpful and concerned? Yes. Check.

If I take him up on his offer, what are the likely outcomes?

- I get closer to my goal in less time

- I look better, sooner than I otherwise would have, improving my social, athletic, and sexual capital; perhaps even financial capital given the studies showing more attractive people earn higher salaries and garner more promotions

- I remove the risk of early death and disease much more quickly, lowering my probability of a significantly negative outcome, saving me money down the line, and making life more enjoyable along the way

- I have access to someone more experienced in this area than I am, letting me extract their knowledge capital at no cost, benefiting from his past efforts. It’s the intellectual equivalent of collecting the dividends on someone else’s stock certificates.

- I add someone to my life that cares enough about others to break social protocol, risking backlash, meaning they are probably a decent person despite lacking tact

Final analysis? Score! This is amazing stroke of luck. Grab onto it. This is like a real world video game encounter giving me a chance to level up faster.

Instead, this woman felt “gutted” because the man who offered to help her said out loud what everyone else already knew: That she was morbidly obese. She let a wonderful opportunity pass, to her own detriment, because he made her feel uncomfortable despite his good intentions. She knows she’s fat. She is working on changing the fact she is fat because she doesn’t like it. Yet, she wants to delude herself, on some level, that everyone around her is ignorant of this fact by refusing to own it. If she did accept that everyone else is aware of it, she wouldn’t have been embarrassed any more than if he had pointed out her hair color, race, age, or nationality.

I, and most successful people I know, would have jumped up, given him a hug, said, “You know, I’ve already lost almost 18 pounds but this could accelerate my efforts. Your timing is perfect. Give me your contact information and let’s setup a time to meet and formulate a plan.” We’d have done the same if it were a business opportunity, a chance to learn some skill we wanted to learn, or any other beneficial offer.

Even more perverse, her reaction is to be discouraged and want to quit her weight loss journey. It’s very unusual for a person to isolate this sort of sub-optimability to one area of their psyche as mental constructs like this spill over into other areas and you very rarely see it in the children of the successful. It’s highly unlikely this poster, under her present mindset, will ever make it into the top 10% of income, ever do anything extraordinary with her life, or ever reach the top of her chosen field, even if she is just as smart or just as talented as those who are. She is her own worst enemy. Her weight, in this case, is merely a symptom of how she deals with things that cause her discomfort. It’s hard to get ahead in life if you act like this.

You Cannot Correct What You Will Not Acknowledge

You cannot correct what you will not acknowledge. Knowing something isn’t enough. You have to acknowledge it. Own it. Forget your pride, forget your ego, and do whatever it takes to improve yourself. Less successful people fall into this trap all the time. They won’t raise their hand during a lecture, asking a question, because they worry it will make them look dumb. Who cares? Sam Walton used to go to trade meetings and talk to everyone he could throughout the supply chain, extracting every bit of information because he owned the fact he knew nothing and was at a huge disadvantage to competitors. He was a learning machine. As a college student, Warren Buffett would take the train another city, pound on the doors of corporate headquarters, and spend the day asking questions of an executive to understand an industry upon which he didn’t, yet, have a grasp.

That is, successful people are willing to look stupid in the short-term to end up smarter in the long-term.

[mainbodyad]When you grow up in a household of successful people, this attitude gets subconsciously absorbed more often than not. Watch the grown children of successful people at college. If something goes wrong, they take action, often without parental involvement. They’re organizing study groups, talking to the professor after class, signing up for a tutor, or tracking down others who have taken the class before them to try and gain an advantage. You rarely see a self-identity crisis; “am I worth it?”, “am I stupid?”, “do I belong here?”. To them, the sub-par performance is nothing more than a problem to be fixed on the road to where they are inevitably going to end up – with a good job, a lucrative income, and maybe a vacation house for the summer. The children who grew up without having this inculcated in them end up hiding their failure, doubting they belong, and, in many cases, dropping out of school despite having nearly identical academic achievements. This is one of the challenges of upward mobility in the education (and, thus, income) system. On May 15, 2014, The New York Times magazine division published a fantastic essay about it, and what one Texas University is doing to try and solve it, that is worth reading.

Sometimes, acknowledging reality means accepting things that can’t change. I was reading an online account the other day of a scientist. He loves his son, but his son was simply not college material. His boy didn’t have the intellect and cognitive ability to make a career from his mind. The father was posting about how he had to fight with the counseling department at the high school – which refused to accept what was plainly obvious – to get his boy off a college path and focus on trade school, instead, where he could work with his hands, improve the world, and make a good living. Today, his son is doing well in his field, has no debt, makes twice the income his former classmates do despite them having a degree, and is working his way through community college, paying cash, so he’ll eventually have the piece of paper, anyway. The successful father saved his kid a decade of lost opportunity by acknowledging the facts and adapting his strategy to do the best possible with what was on the table. That’s your model. That’s how you want to teach your family to act.

The short version of all of this is, if you want to give your kids some of the advantages of successful families, teach them to become heat seeking missiles themselves by:

- Owning their mistakes and shortcomings, acknowledging in objective terms where they are behind the curve

- Seeing those mistakes and shortcomings as temporary failings that are not indicative of where they will end up in the future nor an inextricable part of who they are provided they are willing to change the behavior that caused them, or accepting that which cannot be changed and adapting the strategy to maximize the best possible outcome within those confined parameters

- Taking advantage of any and every opportunity that offers a good trade-off, consistent with their moral values

- Sacrificing their ego, pride, and short-term wants for their long-term objectives

Life gets a lot easier, and a lot more fun, when you have this disposition.