Reynolds Tobacco Company and Its Legendary Employee Stock Ownership Plan

Following up on the article I wrote about cigarette market share in the United States, I thought this was a great story about the legendary employee stock ownership culture at Reynolds Tobacco back in the first half of the 20th century. It comes from Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco, which you should buy. It explains how R.J. Reynolds almost forced his employees to buy stock in the company and even created a special class of dividend shares for them!

Free from the grip of Northern interlopers, Mr. RJ immediately moved to ensure that his company would never again fall into the hands of “the New York crowd.” He began force-feeding Reynolds stock to its employees. “You should have an interest in this company,” he told them as he arranged for bank loans to buy stock. Never mind that many workers didn’t want to go into hock; Mr. RJ said he knew what was best, and he did. As the value of Reynolds stock ballooned in the coming years, Winston-Salem came to be known as “the city of reluctant millionaires.”

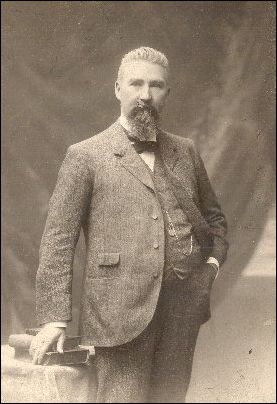

Image of Richard Joshua Reynolds, or R.J. Reynolds, founder of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company of Winston-Salem. Public Domain Image Taken Circa 1890.

Soon Mr. RJ went even further, creating a “Class A” stock – known locally as anticipation stock – designed to put all voting power in the hands of workers. It paid an extraordinarily rich dividend: 10 percent of all profits in excess of $2.2 million. Workers clamored for the new issue, and many used their salaries to buy all the Class A they could. The annual dividend payment became a kind of local holiday, a time local car dealers and luxury purveyors eagerly awaited. The story was told of a Winston-Salem tyke who received a horde of presents on Christmas morning, only to begin weeping uncontrollably. He said he’d had his heart set on Class A stock. From the early 1920s until the IRS disallowed the Class A in the 1950s, Reynolds employees controlled the majority of the company’s stock.

In return for its security, Reynolds took special care of its workers. The company loaned employees up to two-thirds the value of their property, operated lunchrooms at cost, and always had ice water on hand in the steamy tobacco factories. It provided day care for the children of women workers – one for the whites, of course, and one for the blacks. Reynolds even ran a supervised rooming house for country girls who came to Winston-Salem to work, and provided housing for another 180 families at cost.” – Page 45

“At a time when southern businesses were generally controlled by absentee Yankee owners, here was a company under local control raining cash on its community.” – Page 46

“Factory workers in overalls walked into stockbrokers’ offices with paper bags full of cash and “buy” orders for Reynolds Tobacco. A factory worker named Hobert Johnson was one of the company’s biggest shareholders for years, snapping up all the Class A stock he could afford every time some became available. Shares were handed down from one generation to the next, with an admonition: “Don’t you ever sell that Reynolds stock.” – Page 48

Part of this success, no doubt, came from the fact that “In 1960, 58 percent of all men and 36 percent of all women smoked.”