An $8,000,000 Investment Mistake of Omission

One of my favorite topics from mental model studies and investments are the tendency of people to focus on mistakes of commission rather than mistakes of omission. This area has received some press in recent years as a result of people like John Bogle and Warren Buffett talking about the opportunity cost of spending too much on investment expenses, or walking away from a good holding. Yesterday, Aaron and I went to Dick’s Sporting Goods to look at golf supplies and as we made our way back to the parking lot, I was struck by the thought that crosses my mind every single time I enter one of the stores: How my own family walked away from a staggering amount of wealth due to a very stupid mistake of omission that never should have happened. The last time I mentioned it was four years ago, in passing, in a post about finding investment ideas. A fuller explanation might be useful to you.

Nearly a quarter century ago, my grandmother owned a sporting goods retailer in Northwest Missouri with one of her six children. My case study file cabinets include decades worth of her handwritten financial statements, tax documents, and other records. They had started with a few thousand dollars and built it into a very good small business that, in inflation-adjusted terms, was delivering a decent amount in per annum in sales, which they had assembled from nothing, old-school style (the Internet wasn’t a thing then, so this was people coming in and paying cash to buy baseball bats and running shoes).

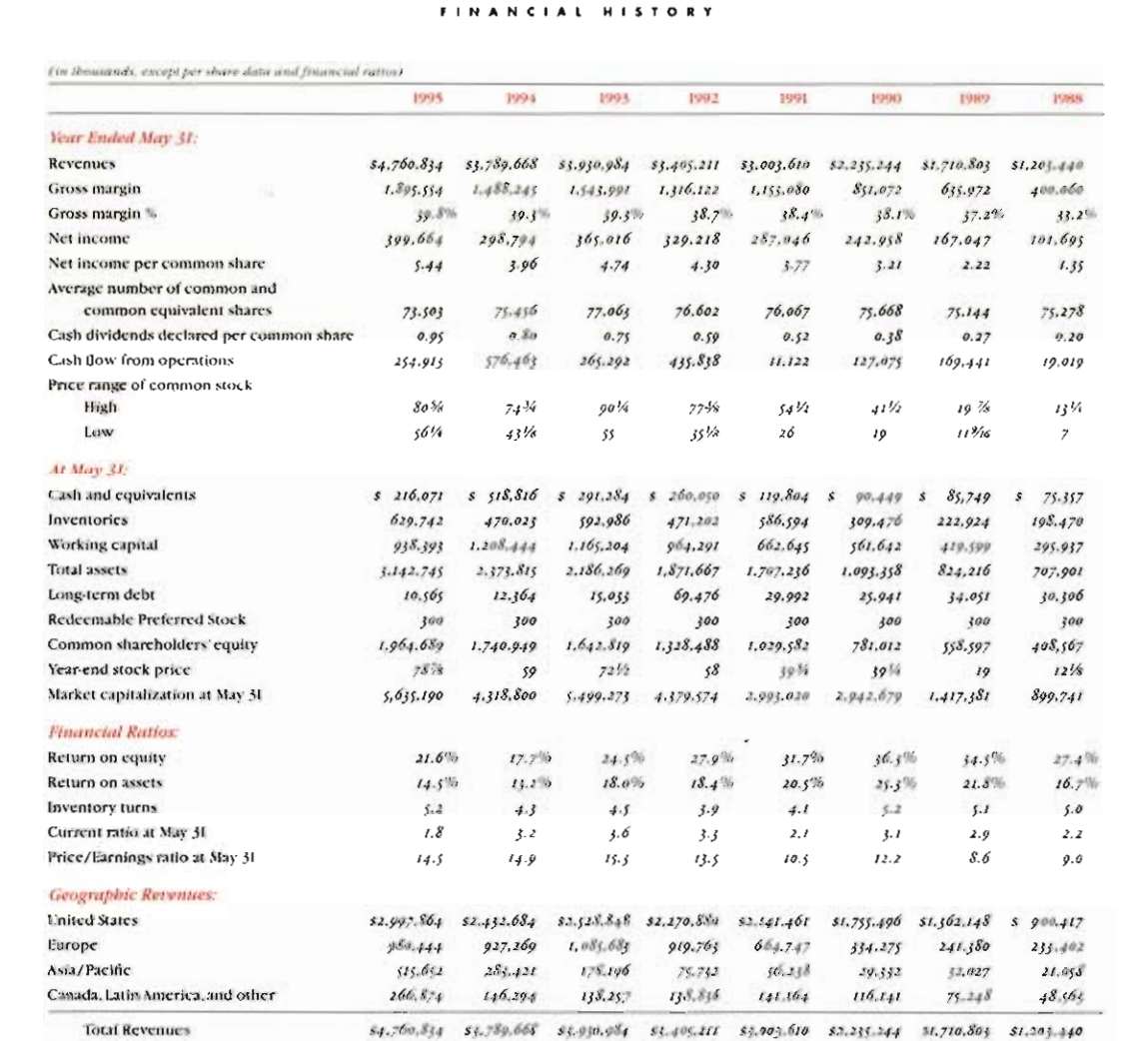

During these years, the store generated a large part of its profits from selling a handful of brands, one of which was Nike. They had observed its apotheosis into the global sporting goods empire, retelling the story of its founding with wonder and awe. They knew how profitable Nike had become. They expanded their Nike offerings as Nike moved from shoes to apparel to accessories. They stood around and talked about its obsession with stockholder profits to the point it was breaking the rules of the industry by engaging in verboten acts such as rapidly turning over road salesmen to avoid giving them raises (Nike operated under the assumption its brands didn’t need selling as they were in demand, so the sales staff was nothing more than physical bodies tasked with taking orders, which, to be fair, was accurate in their case). They marveled at its brand power, getting teenagers to drop hundreds of dollars without batting an eye. They knew season after season, year after year, the backlog grew as people began to trust Nike for all of their needs, be it football, track, golf, soccer, or tennis. Being entrepreneurs and having the ability to read financial statements, a single glance at the annual report would have shown them the double-digit returns on capital, dividend hikes, low debt load, and large insider equity stake. (Nike has its annual reports online going all the way back to its initial public offering. If you want to download this report for 1995, I’ve made it available in Adobe PDF here.)

Nike’s financial records were astounding, and confirmed everything they saw, and knew, as one of the biggest Nike retailers in the region. Here is a scan of the 1995 annual report, showing an 8-year history up until this point, long after the IPO days were over and the firm had already become one of the largest enterprises on the planet. And the price-to-earnings ratio was stupidly low! This amazing business, with 20%+ returns on capital, exponential growth, rising dividends, and expanding market share was trading at a 6.9% base earnings yield! By every objective measure, not only was it one of the best companies in business at the time, it was cheap with practically no debt.

Investment Knowledge Alone Isn’t Worth Anything If You Don’t Act On It

Throughout my entire childhood, marveling at Nike’s continued ascension was always there in the background, putting food on the table and profits in the pockets. Reselling Nike products helped pay for their houses, cars, clothes, and furniture. Yet, none of them ever took the logical step of becoming an owner despite endless chats about the firm. They had a front-row seat, and access to information 99% of the population didn’t have by virtue of their position in the supply chain, and they did nothing with it. Had they taken even a modest portion of their annual partnership earnings and bought a block of stock each year to put into a bank vault, they would be sitting on millions of dollars in surplus wealth, pumping out hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual dividends. It was the closest thing to a grand slam they are likely to get in their life, smack in the center of their circle of competence, and they let it sail by, slowly, throughout their entire working career until they ultimately sold the business without a single share on the books.

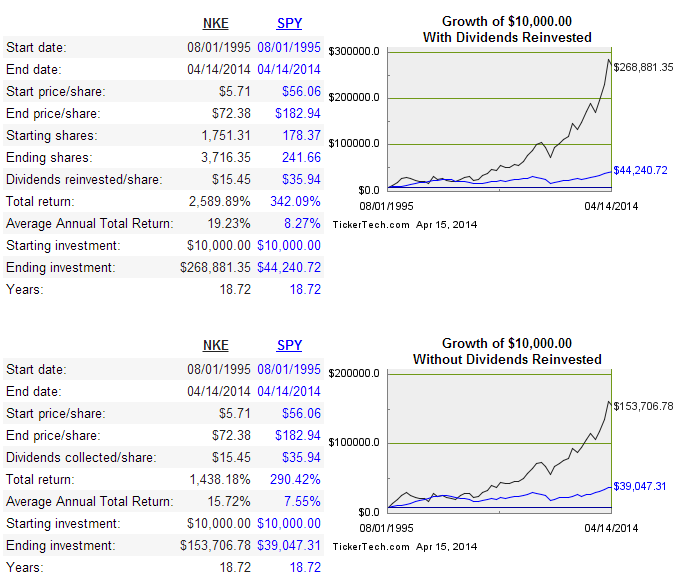

To put the opportunity cost of this failure to act into perspective, let’s look at some numbers. Let’s assume that they didn’t buy shares when the company first went public in 1980. Let’s assume they didn’t buy shares a decade later, after it had grown much larger and they were stocking the products in their retail store. Let’s, instead, assume they bought their first shares a full 15 years after Nike’s IPO, when it was already one of the largest sporting goods companies on the planet, it had a long history of financial data behind it, and the ship, as it were, appeared to have sailed. This is partially me being kind to them as if I calculated the performance from the earlier dates, the numbers would cause them to weep at the fortune they missed. It’s also partially for the sake of efficiency as Nike has a handy investment calculator that goes back to this period, saving me the time necessary to break out the spreadsheet and do a full case study.

Here is what a $10,000 investment would have done based on whether or not dividends were reinvested, compared to a comparable investment in the S&P 500.

What about dollar cost averaging? How would that have changed the picture? Updating my own files, based on even the worst case assumptions, current market values, and tiny investments as a percentage of revenue – enough they wouldn’t have even noticed if they replaced only one part-time employee – from the time they began carrying Nike years prior to 1995 through the day they sold the sporting goods store, my extended family walked away from at least $8,000,000 in Nike shares over the years, up considerably from the last time I calculated this failure. Given where they were, what they knew, how involved their day-to-day lives came to be with the company, and their constant discussion of the enterprise, it’s an inexcusable oversight. That money should be in their bank vault at the moment, yet it’s not. It belongs to someone else. Eight million dollars that should have belonged to the sporting goods store. Gone. (I’d give you the complicated math but I’m not too keen on publishing the detailed financials, even though the company hasn’t existed for decades. Maybe in another twenty years I’ll use them as a teaching tool.)

And it wasn’t just Nike. That is what makes it so painful. They repeated this mistake with half-a-dozen other companies, squandering millions upon millions more in wealth that could have been theirs; that they had a huge advantage over the general public in spotting, and with which they were intimately engaged on a regular basis and that they had the skill set and experience to understand.

The Lessons from This Horrible Investment Mistake of Omission

Every situation has in it the seeds of wisdom. What can we learn from this investment catastrophe?

- Each of you, right now, has something in your life that is probably staring you right in the face. It’s an opportunity that could change your destiny, or if planted this year, could generate huge fruits in the future. You know you should do it. You have the information you need to do it. Yet, you haven’t acted on it. Why?

- You’re going to miss great investments. It cannot be helped. It’s the nature of the game. You don’t need to get them all. You don’t even need many. In fact, one above-average investment can change your family forever, while one bankrupt investment can easily be overcome if your portfolio is well structured. This is why I constantly harp on the Eastman Kodak case study, to drive home the math involved.

- Often, you look at a situation and think it’s too late to take advantage of an intelligent course of action. This is rarely true. Nike was already huge in 1995. However, the earnings were still marching upwards with a lot of area left in which the firm could grow, replicating its success.

- It often takes only a modest effort to lead to outsize results if you give it enough time to accrue to your benefit. The typical married couple, both of whom have bachelor’s degrees, will earn lifetime household income of $4,536,000. You have the dry powder to come up with capital if you really desire to build an investment portfolio. Unless you’re facing catastrophic health care costs, everything else is simply an excuse.

My family benefited from it because I vowed as a teenager I wouldn’t let my parents make the same mistake with their business. It’s taken 15+ years, but I’ve diversified them away from their manufacturing business as they’ve diligently put aside a portion of their monthly cash flow. They now collect dividends from almost fifty different companies, in multiple currencies, across a diversified range of economic sectors. They enjoy a constantly expanding stream of direct deposits from their share of earnings selling ice cream, cheeseburgers, light bulbs, oil, natural gas, jet fuel, shampoo, conditioner, soap, deodorant, toothpaste, baby powder, mouth wash, bleach, credit cards, chemicals, cleaning supplies, cereal, chocolate, pharmaceuticals, escalators, jet engines, gold, silver, iron ore, copper, uranium, salad dressing, peanuts, software, movies, video games, oatmeal, logistics, tea, railroads, insurance, furniture retailers, newspapers, specialty retailers, spices, jams, jelly, and peanut butter, cooking oil, construction, hair dye, lipstick, and shipping contracts.

I calculate the intrinsic value of their holdings every month or two, give them a shopping list of stocks I think they should consider acquiring or adding to their existing position, and let them pick what they want. Little by little, piece by piece, share by share, they’ve built something meaningful. They will continue to be a net purchaser of investments that throw off surplus dividends, interest, rents, and royalties every year for the rest of their lives. Just a few days ago, I was on the phone with my mom, who decided she wanted to buy more ownership in a British mining company. It fills this investor’s heart with joy to finally see the result of long-term planning; to finally be at the point where my parents collect Euros from an oil conglomerate in France and Swiss Francs from a confectionary empire in Switzerland.

Each of you has some sort of situational knowledge that gives you an advantage over nearly every analyst working on Wall Street. Take advantage of it. Otherwise, you’ll look back on the past two decades with the same regret at missed opportunity, knowing the perfect shot was lined up for you and you never swung. The world will be content to let you sit there as others collect your prize. Don’t let it happen. Do something intelligent. Action is required. The stakes are enormous, especially if you are young.

I still tease my grandma from time to time about her Nike mistake, but the interesting thing is, it’s not the one that upsets her. For decades, she talked about buying shares of Dollar General. She saw it when it was a tiny company, shopped in its stores, and knew the business itself had great economics. Year after year, when we would go to lunch, she would say, “I need to buy some stock in Dollar General.” Until one day, in 2007, it was bought out by a private equity group (it’s subsequently gone public again). To this day, she’s still never bought a single share of the firm.