Performing Beethoven’s 9th Symphony with the New York Philharmonic

One of the benefits of our relocation to the West Coast was going through boxes and containers dating back to early childhood, discovering things that we didn’t realize we had; toys from our nursery, birthday cards from elementary school, choral music from high school and college. This included migrating old computer archives before destroying the physical drives, resulting in large amounts of data we now need to organize and catalog over the coming years as a part-time personal project.

One of the caches we recently discovered came from our college days. Travel back in time with me, if you will, to 2003.

- 1 out of 4 Americans alive right now had not, yet, been born.

- The 1990s dot-com boom was still close enough to feel like it was somewhat recent. That same year, 2003, Yahoo was the dominant search engine with Google having a number two market share followed by MSN, AOL, AskJeeves, Overture, Infospace, Netscape, Altavista, and Lycos. In fact, Yahoo, Google, and MSN were almost neck-and-neck with a little more than 1/4th market share each. Technology companies had been imploding left and right, bankruptcy after bankruptcy. Much of the country was using dial-up Internet or, if they did have a higher speed option, DSL through the phone lines.

- It was a little less than 26 months after the September 11th attacks.

- Online video was little more than a gimmick. YouTube wouldn’t exist as we know it for another two years – if you wanted to see a video clip, you had to find a reference library that had it in its archives then watch it on film in the library.

- Facebook hadn’t been invented, either.

- The iPhone wouldn’t be released for another four years. If you wanted to take a photograph or video, you had to use giant recording equipment or lug around a camera. Most people still had the telephone numbers of their friends and family memorized. Pay phones were still a fairly frequent sight in cities, at airports, etc., so if you needed to make a call, you’d take change out of your pocket, insert a few coins, and dial. If you wanted directions to get somewhere, you had to buy a map or go to MapQuest.com then print the step-by-step instructions on paper, which you followed as you tried to drive.

- I had only been writing the Investing for Beginners site at About.com for three-and-a-half years, still fresh off the days from when I had to code my articles in an html text editor and upload them via FTP. (It would still be a year before I signed my book deal and did my two internships; a year-and-a-half before I read Poor Charlie’s Almanack for the first time; when we registered the domain that would come to host our sporting goods business, playing a large role in the following decade of our lives. During this period, I had only recently become the Student Body Treasurer and the Chairman of the Student Finance Board for the Student Body Government, concerning myself with approving expenditures for pizza parties and on-campus dances for various social clubs.)

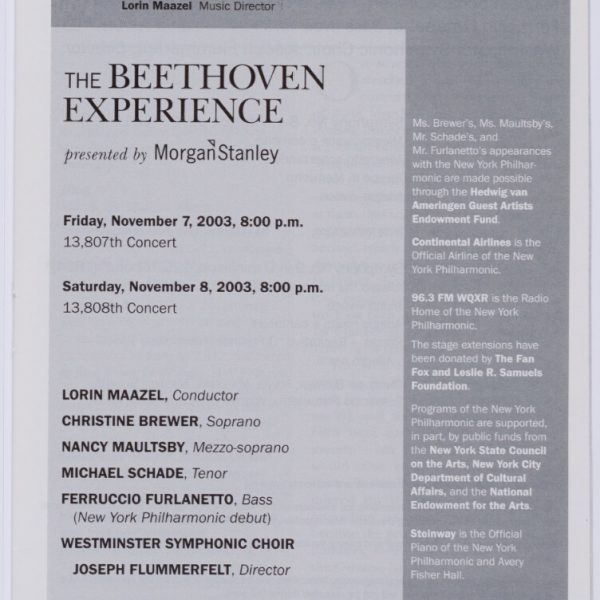

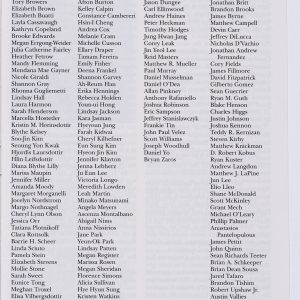

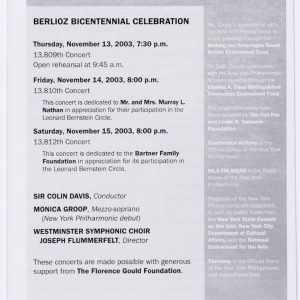

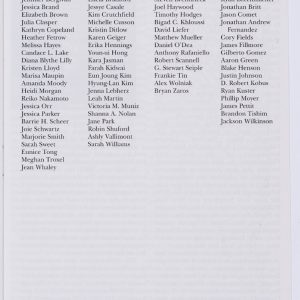

Aaron and I had just turned 21 years old. As part of the requirement for our degree program at music school, we had to participate in the Symphonic Choir. The conducting department this particular year needed to put together two separate performance groups for a series of concerts in New York City. This was as much art as science as they found it necessary to blend the specific types of voice for the specific repertoire to be sung. As it so happened, both performance groups were going to be singing with the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center. My assignment: The Beethoven Experience concerts, held Friday, November 7th through Saturday November 8th with Lorin Maazel conducting. Aaron’s assignment: the Berlioz Bicentennial Celebration, held Thursday, November 4th through Saturday, November 6th, with Sir Colin Davis conducting.

Somehow, someway, despite not being allowed to take photographs, and not having access to technology that would make it easy – hence the blurriness of the pictures (no quick focus or high megapixel images) – Aaron, knowing that this would someday be important to us and we’d want to remember it, managed to sneak a few photographs of one of the performances to which I was assigned, both of the moment prior to the choir and orchestra taking the stage after all of the musicians had been seated. I’m so glad he did.

Unfortunately, we don’t have any of his performance or even of most of the performances we were in over the years, though the program in which Aaron performed is also available through online archives at The New York Philharmonic …

Maybe we’ll discover more as we continue to catalog the vast troves of data we saved. We’d really like to find the Brahm’s Requiem we did together on November 8, 2004, this time with the Dresden Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center. That was, hands down, probably my favorite performance during this period of our lives.

We look back on these years with fondness. When we were underclassmen, I remember going to the main rehearsal hall, the Playhouse, to watch Riccardo Muti prepare the juniors and seniors for a performance of Verdi’s Requiem. Our professors were accomplished performers and academics themselves. Going to the piano department recitals was a joy. In the vocal department, several of our professors were performers at the Metropolitan Opera so attending their on-campus recitals felt in a lot of ways like a private concert. In December of 2017, we visited for Christmas … we were so busy with the asset management firm, I didn’t have time to blog about it but maybe I’ll dig up those pictures and post them.

Many times, you’ll hear successful men and women talk about how certain experiences gave them an advantage they didn’t expect. I know people who credit their success to the years they spent playing a specific sport – practicing, training, improving while competing, and even failing, in front of others, sometimes as an individual, sometimes as a member of a team. I know others who credit their success to their first job at McDonald’s when they were a teenager – being forced to learn a system, handle multiple things at once, deal with angry customers, pay attention to details, and stand on their feet for hours even when they would rather be doing something else. I know quite a few people who credit playing poker to changing how they viewed the world, thinking about things probabilistically and learning to act with calculated efficiency even if it meant losing in the short-term.

For us, our years spent studying and performing music, specifically choral and classical music, played a huge role in endowing us with certain advantages that might not seem readily apparent.

It taught us that willpower is a muscle. You can make it stronger or weaker depending on whether you exercise or neglect it.

It taught us that discipline is a skill. You have to learn to manage yourself, and others; specifically your time and resources.

Studying and performing music was akin to an intense training regiment. It forced us to spend hour after hour, day after day, week after week, month after month improving, perfecting, and getting to the point of effortless fluency even when our schedules were packed or there were other things we would have rather been doing. We weren’t just learning Beethoven and Brahms, hymns, carols, and opera, we were learning how to manage ourselves. It taught us to put protective barriers around our time – if you had to practice, you had to practice, even if it meant telling other people you weren’t available for social engagements – as well as to respect the time of others.

It taught us to objectively measure ourselves as much as possible; a technique we still employ when evaluating our results both personally and professionally. This was a natural outgrowth of recording ourselves each week, including lessons with our voice teacher, so we could step outside of our own bodies and hear ourselves as the audience heard us, analyzing our performance as close to an impartial by-stander as we could. It taught us to separate ego for the sake of growing and becoming more masterful at our craft. It taught us to handle criticism, both one-on-one and from a crowd – musicians are routinely forced to perform in studio groups, performance classes in front of the entire student body of their peers, and/or juries of faculty members, who can hold you back for a year if you weren’t making sufficient progress, subjecting themselves to withering criticism and learning to separate the critique from their own ego; a concept that should sound familiar by now. That experience also had the added bonus of acclimating the performer to being in front of an audience. (Right now, you could put a microphone in my hand and ask me to go out on stage in front of thousands of people to talk about anything that interests me and I could do it with little to no warning. It’s just not that big of a deal. It’s familiar. Standing there in front of a sea of faces looking at you as blinding, hot lights shine directly on you from the rafters … I’ve done it so many times, it takes about as much mental effort as ordering a cup of coffee at Starbucks.)

It taught us to love the mastery of something for the sake of doing it well, even if no one was listening; for the joy it could bring you due to a job well done.

It taught us the importance, and value, of having healthy emotional outlets for creativity and self-expression. (There are few things in life more wonderful than sitting down to a piano on a quiet winter night as the snow falls outside, playing Christmas music gently to yourself.)

Your life can be materially enriched by picking a discipline and engaging in it. It could be art – learning to draw, paint, or sculpt. It could be music. It could be sports. It could be woodworking. It could be creative writing. It could be learning a new language. It could be cooking or baking. It could be sculpture. It could be making perfume. It could be sewing. It could be comedy or improv. It could be ice skating. It could be gardening. Excellence often comes from being able to wake up one day and decide – even if you don’t feel like it – that you are going to throw yourself into something, fully willing to fail miserably while you learn the ropes, not caring how you look or about criticism from others. You must have the courage to fail, realizing that failure is not a permanent state, but merely a temporary condition as long as you are alive.

Aside from being happier in the long-run, you may be shocked at how your mind builds connections. Diversifying your neural pathways can sometimes lead to powerful insights. Consider the pictures included in this post. Around this period, I had become obsessed with the DuPont Return on Equity analysis. In the same way certain song structures had a specific form – a sonata, for example – all business in a free market system with free players was essentially conducted through the framework, or song structure, of the variables in that calculation. In the way a Haydn and Mozart symphony might differ, but still adhere to the same basic structure, entrepreneurs like Sam Walton, Walt Disney, and Warren Buffett were simply “playing” or “composing” their own variations on the DuPont ROE formula differently. It was the key to everything. In the end, all cash flow and profit came down to what was happening to those variables. Those were the levers management had at its disposal to generate wealth. It was the Rosetta stone; the holy grail. It provided the framework which launched me years, even decades, ahead of where I otherwise might have been. It is the technical basis that underlies virtuosity. This is one of the reasons I remind you that “it’s all connected” fairly frequently. Life does not exist in self-contained academic disciplines that do not intersect. Universities are structured that way, the universe is not.