I’m Starting My Week by Buying More Shares of Nestlé

I put in and order on Saturday to buy a few more shares of Nestlé SA on Monday for my family’s personal accounts. I spent much of the weekend reading the company’s 125th anniversary biography and studying the original balance sheets and income statements of the firms that went into forming one of the world’s most profitable holding companies.

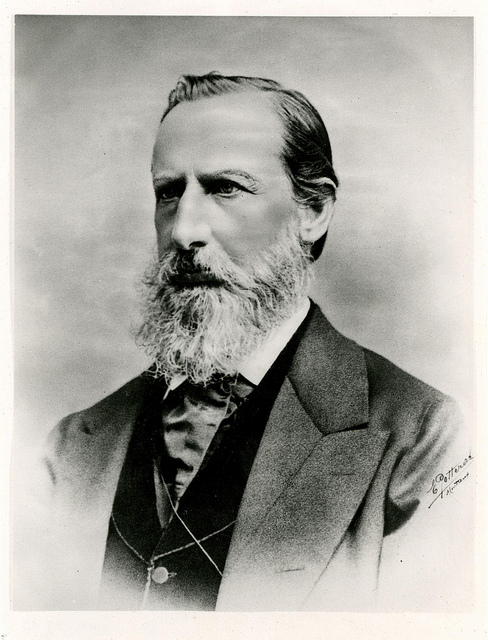

I still think it’s amazing that Henri Nestlé started a business in his 50’s, and in seven years, grew it to the point he sold it in the late 19th century for 1,000,000 Swiss francs; a staggering sum in those days. The new owners grew it to 10x its size in another seven years or so before it was acquired by an equally impressive company, the Anglo Swiss Condensed Milk Company. Henri never invested in the firm after he left, not even owning a single share. Instead, he took his capital and retired with his wife. They never had children, so they spent their days doing whatever it was they wanted with no financial worries . He was not motivated so much by money or business, unlike people who bought his company, as he was a way to lower the infant mortality rate, which stood at 1 out of every 5 babies. His baby formula and cereal invention was really revolutionary.

The business is still run on a decentralized basis, with individual operating companies sitting under the parent holding company in Switzerland. It’s the same model followed by Berkshire Hathaway and Johnson & Johnson so that individual businesses are managed in the most intelligent way for their own markets.

I ran some spreadsheets and to give you an idea of how staggering the company’s historical dividend growth has been – the businesses they own can raise prices almost every year to offset inflation – I thought it would help to frame it in modern terms.

Let’s take the age of the world’s most famous investor, Warren Buffett. He is 82 years old at the moment. I am 30 years old. That is a 52 year age difference. Imagine, for a moment, that Nestlé were capable of maintaining its same dividend growth rate over the next 52 years that it has in the past, through recessions and depressions, global wars, inflation, deflation; you name it.

If the firm could achieve that (and there is no guarantee it can, this is simply to illustrate how impressive past performance has been), a single share bought today for CHF 64.50 in Switzerland would pay, over the next 52 years, aggregate pre-tax cash dividends of CHF 3,500.00. In the final year, the dividend would be CHF 333.60 and, if the yield were comparable to what it is today, the share price would be CHF 10,109.18. (Assuredly, the stock would have split many, many times so the actual exchange listing would be much lower, you’d just have a ton more shares.)

The job of the investor is to discount that back to the present, factor in inflation, taxes, and other reductions in purchasing power, and compare it to the cash outlay today to determine if the bargain is a favorable one. Do it right just a few times in a lifetime and things tend to work out extraordinarily well without a lot of subsequent effort.

Of the 15,000 publicly traded businesses in the United States and the 30,000+ around the world in the more developed markets, there are probably only 100 companies that I would ever consider for inclusion on the “permanent” list; shares that are bought and held forever. These are businesses that have almost non-assailable brand equity (and even that is no guarantee – Brut cologne was once one of the most prestigious fragrances sold in the world and now, only the good stuff is sold in France; in the United States, a cheap knockoff using the name is sold at Wal-Mart for a few bucks). They have a built-in resistance to inflation. They have the ability to raise prices almost every year. They have some sort of legal protection in the form of trademarks, patents, or copyrights. They have a strong balance sheet. They enjoy very high returns on non-leveraged equity. The products never, or rarely, change. They appeal to some basic human demand and aren’t likely to go in and out of fashion. They are not likely to turn into a basic commodity (e.g., what happened to pearls at the end of the 19th century).

These are companies like Brown-Forman, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Hershey, Clorox, and Procter & Gamble. They are extremely rare. When you find one trading at near its intrinsic value, it’s often a much better buy than a secondary or tertiary firm selling at a substantial discount due, in part, to the leveraging effect of deferred taxes. You go back and pull the dividend record for 25 or 50 years and see that the increase over time has far exceeded the rate of inflation.

Most of the time, the 100 firms on my list are recognized for their quality and trade too high to get a fair deal. (I’ve never seen Hershey’s affordable once in my entire adult life.) When they are in range, though, I think the best course of action for someone who has no credit card debt, plenty of savings, and a diversified income stream, is to write a few large checks and then stick them in a bank vault for a generation or two. You check the annual report every year and, as long as things are still humming along nicely, you keep holding. Short of a catastrophic event that I cannot foresee at present, I expect to leave the Nestlé shares I’ve been buying to my grandchildren someday. In the meantime, I get to spend the cash the firm sends me every year on furniture, video games, travel, clothing, or reinvestment, depending on what I want to do at the time.

Anglo Swiss Condensed Milk Company Headquarters

And what if Nestle someday fails? I can’t imagine that happening soon, but if it did, it’s only a matter of time before the dividend rebate effect results in me having extracted my entire initial purchase price from the investment. Not that I wouldn’t be upset, but if the unthinkable happens, and I don’t see it coming, at the very least we’re only talking about house money at that point. My original principal would have long been recaptured and redeployed.

I’ll stop posting about Nestlé now. I would think many of you are not interested anymore (though if that were the case, you wouldn’t have clicked on this post in the first place, I suppose). It’s hard … if you understand international accounting standards and go through the finances yourself, you want to take out a megaphone and start yelling about finding a firm that has economics that place it in the top 1% of all businesses to have ever existed.

I’m still hoping to get over to Europe sometime in the next six months to a year, but don’t know if I can fit it into the schedule. I’d love to tour the main campus.

Update: Several years ago, I placed this post, along with thousands of others, in the private archives. The site had grown beyond the family and friends for whom it was originally intended into a thriving, niche community of like-minded people who were interested in a wide range of topics, including investing and mental models. I decided, after multiple requests, to release selected posts from those private archives if they had some sort of educational, academic, and/or entertainment value. On 05/22/2019, I released this post from the private archives. This special project, which you can follow from this page, has been interesting as I revisited my thought processes about a specific company or industry, sometimes decades later. In this case, reading about how we approached the analysis of a real-world business was helpful to many of you and the information contained herein is now so old there is no chance a reasonable person might mistake it for current market commentary.

One major change that has occurred in the years since this post was originally published: Aaron and I relocated to Newport Beach, California in order to have children through gestational surrogacy. Within a window of a couple of years around that relocation, we also sold our operating businesses and launched a fiduciary global asset management firm called Kennon-Green & Co.®, through which we manage money for other wealthy individuals and families. That means we are now financial advisors (or, rather asset managers operating under a investment advisory model as we are the ones making the capital allocation decisions rather than outsourcing those to fund managers or third-parties), which was not the case at the time this was written. Accordingly, let me reiterate something that should be perfectly clear: this post was not intended to be, and should not be construed as, investment advice. Also, for the sake of full disclosure, I’ll state outright that Aaron and I still own shares of Nestlé personally. We express no opinion as to whether or not you should buy it. Any company can do poorly or even go bankrupt. There are no guarantees Nestlé will generate a profit or make money for shareholders. We may buy or sell Nestlé for ourselves or for private clients of our firm in the future and have no obligation to update this post or any other historical writing. You should talk to your own qualified, professional advisors about what is right for your unique circumstances, goals, objectives, and risk tolerance.

Stated candidly, this post is a historical anachronism from many years ago that arose because we weren’t in the asset management business but, rather, were private investors. In the future, things like this will not be posted on my personal blog but, instead, if they are written, released through Kennon-Green & Co., including letters to the firm’s private clients.