Mail Bag: Do You Still Hold Index Funds in Your Charitable Foundation?

It’s been a long time, but here’s an update on the charitable foundation …

Mr. Kennon,

Unless I missed it, I believe it has been many years since you talked about your foundation (foundations?) and the passive investment approach you use for it/them. Do you still buy index funds? Has anything changed? I enjoy hearing about that part of your life and am thinking about setting up something similar.

Please don’t use my name if you answer this question.

[Redacted]

There have been no major changes other than a recent rebalancing between domestic and international holdings. The family foundation is structured as a charitable gift fund, allowing me to maintain privacy as they don’t require Form 990 disclosures. That means I can only select from a list of pre-approved investment pools and mutual funds. Under such restrictions, I opt for the dumb money approach, hoping only to capture the returns of both the domestic and international equity markets over the next 25 to 50 years. Even though I am of the opinion (but can’t guarantee) that it will grow at a lower rate than the main portfolios under my control, I consider the additional privacy worth the trade-off.

The result: Other than cash balances that occur when Aaron and I make new contributions to the foundation or reserves held by the underlying funds themselves, as of this afternoon, the foundation itself has only two securities:

- 50% of assets are invested in an international index fund

- 50% of assets are invested in a domestic total market index fund

As we’ve talked about in the past equity index funds don’t actually exist. You can’t own an index. It’s an abstract theoretical concept. Rather, they’re a way to formulaically acquire, and conceptually process, a given basket of stocks based on a predetermined set of rules; in this case, a less than perfect rule at that, market capitalization.

That means what the foundation really owns is a portfolio of 4,278 individual stocks (3,356 in the total market index fund and 922 in the international index fund) underlying the line items that show up on the statement. This portfolio of 4,278 stocks is run at a combined expense ratio of 0.09%. (To put that into perspective in terms of how the average investor might think, that means for every $1,000 in assets, the annual costs are only 90¢. There are a few smaller administrative costs on top of that but they’re also relatively insignificant.) The portfolio turnover of the underlying funds is 2% per annum, meaning the implied underlying holding period for each stock is 50 years.

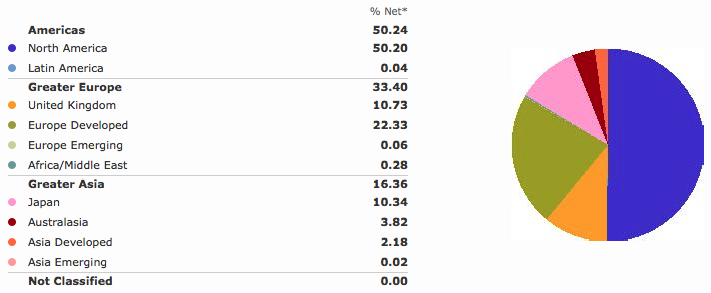

Geographically, the money is spread out across the world. The diversification is much greater than it would appear in the foundation reports when you consider that a lot of the big American blue chips are really multi-nationals generating most of their revenue and profit from outside of the United States. Asia Developed, for example, appears to be only 2.18% but the aggregate economic influence of that region, in reality, is probably ten times that much even in places you might not expect (e.g., YUM! Brands generates a lot of money from KFC franchises in China, yet is counted as an American business because it is headquartered here).

As is the case with market capitalization weighted index funds, the diversification isn’t nearly as widespread as one might be tempted to believe. Roughly 25.14% of foundation assets are invested in the top 50 companies:

- 1.35% of assets in Apple, Inc. (United States)

- 0.93% of assets in Royal Dutch Shell (both United Kingdom and The Netherlands)

- 0.90% of assets in Exxon Mobil Corporation (United States)

- 0.89% of assets in Nestle SA (Switzerland)

- 0.86% of assets in Microsoft Corporation (United States)

- 0.81% of assets in Novartis AG (Switzerland)

- 0.78% of assets in Roche Holding AG (Switzerland)

- 0.74% of assets in Google, Inc. (United States)

- 0.73% of assets in HSBC Holdings PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.67% of assets in Johnson & Johnson (United States)

- 0.61% of assets in Toyota Motor Corporation (Japan)

- 0.58% of assets in BHP Billiton (both United Kingdom and Australia)

- 0.57% of assets in General Electric (United States)

- 0.56% of assets in Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. (United States)

- 0.55% of assets in Wells Fargo & Company (United States)

- 0.52% of assets in Total SA (France)

- 0.51% of assets in BP PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.51% of assets in JPMorgan Chase & Co (United States)

- 0.51% of assets in Chevron (United States)

- 0.51% of assets in Sanofi (France)

- 0.50% of assets in Procter & Gamble (United States)

- 0.46% of assets in Verizon Communications (United States)

- 0.44% of assets in Bayer AG (Germany)

- 0.43% of assets in Banco Santander SA (Spain)

- 0.42% of assets in Pfizer (United States)

- 0.42% of assets in GlaxoSmithKline PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.41% of assets in AT&T (United States)

- 0.40% of assets in Bank of America (United States)

- 0.40% of assets in Commonwealth Bank of Australia (Australia)

- 0.40% of assets in British American Tobacco PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.39% of assets in International Business Machines (United States)

- 0.39% of assets in Intel Corporation (United States)

- 0.38% of assets in Merck & Co., Inc. (United States)

- 0.37% of assets in The Coca-Cola Company

- 0.36% of assets in Gilead Sciences Inc. (United States)

- 0.36% of assets in NOVO-NORDISK A S (Denmark)

- 0.36% of assets in Siemens AG (Germany)

- 0.35% of assets in Citigroup Inc. (United States)

- 0.35% of assets in Facebook Inc. (United States)

- 0.34% of assets in AstraZeneca PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.34% of assets in Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA (Belgium and Brazil)

- 0.33% of assets in Westpac Banking (Australia)

- 0.33% of assets in Vodafone Group PLC (United Kingdom)

- 0.32% of assets in Basf SE (Germany)

- 0.31% of assets in PepsiCo (United States)

- 0.31% of assets in Comcast Corporation (United States)

- 0.31% of assets in The Walt Disney Company (United States)

- 0.29% of assets in Philip Morris International, Inc. (United States)

- 0.29% of assets in Schlumberger NV (Belgium)

- 0.29% of assets in Cisco Systems, Inc. (The United States)

Even though some of the names on the list are not my idea of a good use of money, on the whole, it should work out better than most professionally managed pools.

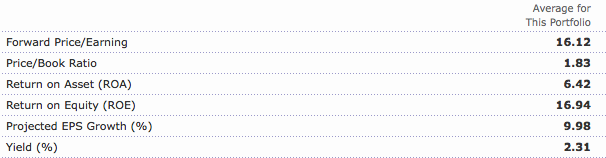

The particular mix of assets I selected for the portfolio based on this simple 50/50 domestic/international equity split results in a basket of stocks that, if we think of them as one, giant, single stock, has the following characteristics:

It is our intention to contribute far more to the foundation over the next 50 years than we distribute in grants, allowing a lot of money to build up tax-free for charitable causes. The volatility is much higher than a typical portfolio but the assets won’t be tapped in any meaningful way for decades so it is of no practical consequence to us. In fact, large losses would be hugely advantageous. If we woke up to a 1973-1974 world where stocks were down 50% or 75%, between the reinvested dividends and fresh charitable contributions, we’d be able to buy a lot more ownership. As we get up toward retirement age, I imagine we’ll start moving a greater percentage of assets to fixed income holdings, providing interest income that we can donate instead of touching the principal itself. If Aaron and I were to pass away before then, the foundation shatters into four sub-foundations, each of which has a trustee that will be given authority to distribute the money under their control as they see fit.

The foundation itself is a wonderful tool to have for our own tax strategy needs. I haven’t made any contributions for awhile (I tend to contribute heavily during market crashes so the last big checks I wrote were back in the 2008-2009 period) but let’s say I wanted to make a large donation. If I had a big block of appreciated stock, I could sign over the securities and irrevocably gift them, taking a tax deduction for the entire amount and never having to pay the capital gains tax that would have been owed. Then, the money can be put to work in the two index funds, compounding tax-free decade after decade before it ultimately goes to whatever charitable purpose we decide to authorize. Or, if we were in a market crash and I had a position with a big unrealized loss, I could sell it, take the loss for the tax credits, donate the net cash to the foundation, write off that amount as a charitable gift, and use the proceeds to buy the index funds. After the wash sale period passed, I could repurchase the stock in my taxable accounts, still pocketing both the tax deduction and the tax credit, and when the market appreciated, all of that money is now in the foundation, where the dividends are capital gains are tax-free. Done correctly, it can add a decent amount to your net compounding rate over a lifetime with no additional risk or leverage. (And that matters – consider that over 50 years, a 3% advantage from low costs and an eye toward tax strategy results in triple to quadruple the wealth owning the exact same basket of securities.)

Personally, I’m thrilled with it, other than the fact it doesn’t offer a reasonably priced small-capitalization index fund, which definitely would have been in the asset mix (over longer periods of time, small capitalization stocks tend to generate a 1% to 2% advantage over larger capitalization stocks since they are growing from a smaller base, even though there can be periods of divergence lasting a decade or more – just look at the late 1990’s when the huge blue chips went into a bubble). In this case, it is somewhat mitigated by the fact the overall mix of this portfolio relative to the S&P 500 results in the average foundation holding having a market capitalization of half the broader index, which was purposeful. In any event, the charitable gift fund structure is a case of a financial product that actually makes the world better. We get what we want out of it, the sponsors generate a bit of extra fee income, and society benefits from the ultimate now-irreversable charitable distributions that must occur at some point in the future. That said, as we get older, I doubt it will be our primary gifting mechanism. If, God willing, we end up with dozens of grandchildren and maybe even great grandchildren, I’d most likely use things like charitable remainder trusts; e.g., our adult kids have a lifetime income beneficiary designation for a pool of assets that, when they die, goes to this or that 501(c)3 but provides them a private pension in the meantime.

Important Information: A lot has changed since this post was originally published many, many years ago. Among the biggest of these changes are that after 17 years, I resigned from my Investing for Beginners site. My husband, Aaron, and I, sold our operating businesses, launched a fiduciary global asset management firmed called Kennon-Green & Co.®, through which we manage wealth for other successful individuals and families including many physicians, attorneys, engineers, managers, executives, real estate developers, software developers, small business owners, and retirees, and moved from the Kansas City, Missouri area to Newport Beach, California in order to build our family by having children through gestational surrogacy.

This post reflects a work written as a personal hobby during a different period in our life when we were private investors and I had a large online following for my financial-related essays and articles. We were not actively engaged in the fiduciary asset management industry at that time. The posts may not reflect our current thinking or beliefs, conditions may have changed, and/or our analysis of a situation may be different. Any specific investment strategies, techniques, companies, securities, or investments mentioned are used solely as examples and neither they, nor any other writing on this blog, are intended as investment advice or tax advice. In both our personal and professional capacity, we may buy, sell, trade, or otherwise engage with any security at any time, including through the use of derivatives, on behalf of ourselves, our family members, and/or the private clients of our firm, without updating my past personal writings or disclosing the operation unless required by law and/or regulation. Investing can involve the risk of loss of principal, including total loss and bankruptcy. Every investor has his or her own unique considerations, circumstances, goals, objectives, and risk tolerances. You should discuss your investment strategy and/or business operations with your own qualified advisors, including your investment advisor, tax professional, such as a CPA, and/or attorney.

Please note that in order for me to feel comfortable maintaining some of the archives on this site, my personal blog, I reserve the right, but have no obligation, to edit any post, including updating graphics and images, reformatting, correcting or clarifying language, adding, deleting, or modifying examples, or otherwise reworking the content in a way that I feel more accurately gets to the heart of the concept I was trying to describe or the phenomenon I wanted to explore. No post, page, or comment on this site is guaranteed for accuracy and may contain errors as it was the nature of the personal, casual, and informal community in which it evolved during the years Aaron and I spent semi-retired in Missouri, expanding our online businesses and investing our personal capital.