Over the past 200 years, real inflation-adjusted returns from stocks have crushed returns from bonds, which have crushed returns of gold.

I write a lot about investing in stock and investing in bonds over at Investing for Beginners at About.com, a division of The New York Times.

There is a reason I tend to be far more favorable to equity investments (stocks) than fixed income investments (bonds) when it comes to long-term investing and why much of my content is focused on the stock market. History has shown that owning businesses – which all a share of stock is; a piece of ownership in a business – generates the best long-term returns as long as you don’t overpay. Most investors don’t have the experience to pick individual stocks so low-cost index funds are a better choice, which I explained in my most recent article, Top 5 Reasons Index Funds Might Be a Better Choice for the Average Investor.

For the more advanced among you, I thought it might be useful to look at long-term inflation-adjusted compounding rates for stocks, bonds, and gold based upon the work of Dr. Jeremy Siegel and John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard.

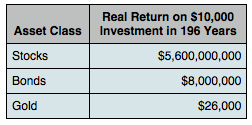

Inflation Adjusted Returns of Stocks, Bonds, and Gold

Going back nearly two hundred years, if you had invested $10,000, reinvested any dividends, interest, or other gains, and left the money alone, how much wealth would have today in real, inflation-adjusted terms based upon the asset class you selected?

The stock investor would have turned his $10,000 into $5.6 billion. The bond investor would have turned his $10,000 into $8 million, and the gold investor would have turned his $10,000 into $26,000. That is statistically significant.

[mainbodyad]For nearly two centuries, stocks have generated an average return of 7% in real, inflation-adjusted dollars. Historical returns show that stocks almost always adjust to inflation over the long-term. After all, if the dollar became worthless and the United States were forced to switch to a different currency – be it gold, silver, or sea shells – companies like Coca-Cola are still going to be generating large piles of excess surplus as people turn in some of their currency in exchange for the product or service the firm provides.

Bonds, on the other hand, have generated average real returns of 3.5% but these are far less uniform than stock returns. In fact, it isn’t unusual to have extended periods where bonds generate negative real returns, something that stocks just haven’t been prone to do. For example, during 1966 to 1981, bond returns on an inflation-adjusted basis were -4.2%. From 2000 through 2010, on the other hands, bonds exceeded the stock market returns (which wasn’t difficult to predict when you look at the incredibly low earnings yield on the S&P 500 relative to Treasury bond yields at the beginning of the decade; you can’t pay 50x earnings for an enormous company such as General Electric or Johnson & Johnson and expect to do well).

If Stocks Are Clearly a Better Long-Term Investment Than Bonds, What Is the Catch?

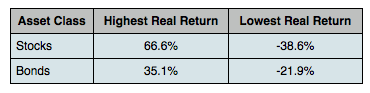

Both stocks and bonds fluctuate significantly. But stocks tend to fluctuate more than bonds, all else being equal. In the past 200 or so years, we can actually look at the highest and lowest real (inflation-adjusted) gains or losses generated by stocks and bonds in any given calendar year:

Depending Upon How You Define Risk, Stocks Can Be Less Risky Than Bonds

John Bogle, legendary founder of Vanguard, puts it this way in his book Common Sense on Mutual Funds:

The data make clear that, if risk is the chance of failing to earn a real return over the long term, bonds have carried a higher risk than stock.

If you consider risk to be short-term market fluctuations, then stocks are riskier than bonds. As periods grow longer, though, stocks begin to beat bonds more and more frequently until any period of outperformance from bonds becomes a statistical anomaly. If the stock market is fairly valued or under valued, it makes no sense for the average investor who is young and has a long-time horizon to be stuffing his or her portfolio with fixed income securities such as bonds.

A Final Word on Gold Investing as an Asset Class

[mainbodyad]Why has gold generated such pathetic inflation-adjusted returns over the long-run? Because gold has no intrinsic value. It isn’t a productive asset. When you own a share of stock, you own a piece of a business that produces goods and / or services to consumers. A good business generates a profit. Every year that passes, gold remains sitting in the vault, but the owner of a company such as Procter & Gamble or Colgate-Palmolive might have a giant pile of cash from the profit generated over that same year by selling dishwashing soap, laundry detergent, and toothpaste.

From a financial standpoint, gold has one purpose: Rank speculation. It can fluctuate wildly and generate huge opportunities for those who are paying attention to gamble – and that is what it is – on governmental fiscal policy. It can serve as a flight mechanism during times of total catastrophic national collapse, such as a Jewish family fleeing Germany during the second world war who wanted to be able to start over with some capital in a new country. But in terms of productive growth, gold is a dead asset that will eventually return to its baseline. It produces nothing. It creates nothing. The inflation-adjusted returns of the past 200 years reflect this reality.