Tiffany & Co.’s Valuation

A Five-Year Re-Examination of the Nation’s Premier Jewelry Store

Almost five years ago, Tiffany & Company was glittering at time when much of the corporate world was still mired in misery from devastating losses and the implosion of Wall Street. Based on the annual report for the prior year, 2010, worldwide net sales had risen by 12% on a constant-exchange-rate basis, reaching $3,085,290,000. After-tax profits were up 39% from the year before, 2009, when the developed world had gone through the worst meltdown since the Great Depression, coming in at $368,403,000. The net profit margin reached 11.9%. The dividend had been raised 47% after the board of directors hiked the payout on two separate occasions. In addition $81 million was spent repurchasing 1.8 million shares at what is, in retrospect, a significantly discounted price of $43.83. Short and long-term debt as a percentage of stockholders’ equity declined to 32%, strengthening an already impressive balance sheet. Return on equity reached 18%. Return on average assets increased to 10%. The total store count rose to 233, an increase of 13 net new stores over 2009 (1 store was closed in Japan, 5 new stores were opened in the Americas, 2 new stores were opened in Europe, and 7 new stores were opened in Asia-Pacific.)

Management, in other words, had done a brilliant job navigating the economic crisis. Despite the volatility in the stock price, the business itself remained profitable even through the darkest nights of the maelstrom. Perhaps this was to be expected. After all, surviving recessions and depressions had been a part of Tiffany & Company’s cultural makeup going back to the earliest days of the firm when a then-25 year old Charles Louis Tiffany opened the doors to his store at 259 Broadway on September 18th, 1837. First day sales at his little emporium came to $4.95. Within six months, a catastrophic banking and real estate collapse occurred that led to the Panic of 1837, plunging the country headlong into a horrific recession that lasted six miserable years before finally abating in 1844. Decades, then centuries passed, the story repeating. There was the panic of 1873. The collapse of 1907. The decimation of 1929-1933. The 1973-1974 equity collapse. The period during which it was owned by Avon and damn near turned into a discount store. The 1987 implosion. The post-September 11th meltdown, and, most recently, the financial crisis of 2008-2009. Through it all, Tiffany & Co. stood, as solid as its now-legendary vault-like storefront, ringing up sales from blue boxes filled with diamonds and watches; selling sterling silver tea sets and gold charm bracelets; seducing with perfume and cut crystal vases, the brand equity reinforced by movies, television, magazines, and literature. Over the years, their master craftsmen have produced everything from fine china to stained-glass lamps that now sit in world-class museums and private collections. (Among my personal favorite: Tiffany & Company produced roughly 50, one-of-a-kind silver handguns back in 1880 to demonstrate American manufacturing superiority.)

Management, in other words, had done a brilliant job navigating the economic crisis. Despite the volatility in the stock price, the business itself remained profitable even through the darkest nights of the maelstrom. Perhaps this was to be expected. After all, surviving recessions and depressions had been a part of Tiffany & Company’s cultural makeup going back to the earliest days of the firm when a then-25 year old Charles Louis Tiffany opened the doors to his store at 259 Broadway on September 18th, 1837. First day sales at his little emporium came to $4.95. Within six months, a catastrophic banking and real estate collapse occurred that led to the Panic of 1837, plunging the country headlong into a horrific recession that lasted six miserable years before finally abating in 1844. Decades, then centuries passed, the story repeating. There was the panic of 1873. The collapse of 1907. The decimation of 1929-1933. The 1973-1974 equity collapse. The period during which it was owned by Avon and damn near turned into a discount store. The 1987 implosion. The post-September 11th meltdown, and, most recently, the financial crisis of 2008-2009. Through it all, Tiffany & Co. stood, as solid as its now-legendary vault-like storefront, ringing up sales from blue boxes filled with diamonds and watches; selling sterling silver tea sets and gold charm bracelets; seducing with perfume and cut crystal vases, the brand equity reinforced by movies, television, magazines, and literature. Over the years, their master craftsmen have produced everything from fine china to stained-glass lamps that now sit in world-class museums and private collections. (Among my personal favorite: Tiffany & Company produced roughly 50, one-of-a-kind silver handguns back in 1880 to demonstrate American manufacturing superiority.)

By the time the end of the first quarter of 2011 approached, shares of Tiffany & Company were offering $2.87 in after-tax earnings, of which $1.16 was paid out as a cash dividend. Investors were willing to exchange their ownership of a single share for a price of $76.04. For the firm as a whole, it represented a market capitalization of $9.69 billion.

Despite my respect for the Tiffany & Company brand and my recognition that management was extraordinarily talented, I felt it was far too excessive for what you were getting in exchange. I wrote a post explaining my disagreement with the valuation in light of the other opportunities that were available at the time (consider that Wells Fargo & Company was still cheap; a far better bargain for long-term investors, as was Berkshire Hathaway). In essence, accepting what amounted to a 3.77% look-through earnings yield before any dividend taxes that would be owed if 100% of those earnings were distributed to owners required everything to go right. There was little to no margin of safety. Why should an investor commit new funds under those conditions? It was not a time to be opening your wallet.

Do you remember what I’ve taught you about an asset that becomes overvalued? Ultimately, regardless of what the price does in the short-term, intrinsic value acts like gravity, dragging everything around it into orbit. It’s a major part of the phenomenon known as “reverting to the mean” in equity prices. This means that the overvalued asset has two probable outcomes over the long-run:

- The asset treads water until the underlying earning power catches up to it

- The asset collapses in price, falling to a more reasonable ratio relative to earning power

Here we are, five years later, and Tiffany & Company shares have demonstrated the former. The high stock has bounced all over the place but ultimately held steady while the net profits per share kept growing. Bit by bit, year after year, the overvaluation burned off. Now, you have this interesting situation where, in early January of 2016, the shares are trading at within pennies of the price they were five years ago ($76.12 vs $76.04 in early January when I began writing this post*). Only, each share of ownership represents so much more than it did. Instead of 233 stores, you’re getting 305. Instead of $17.50 in book value, you’re getting $22.25. Instead of $2.87 in after-tax earnings, you’re getting $3.83. Instead of $1.16 in cash dividends, you’re getting $1.60.

And all of that was achieved despite an incredibly painful, high-profile, bitter fight with the Swatch Group that ended in a nearly $300 million after-tax charge to earnings, wiping out almost an entire year of profits. The ruling was reversed on appeal but none of the money has, yet, been returned to the firm. (The situation is complex. If allegations are to be believed, the watchmaking powerhouse with which Tiffany & Company entered a 20-year agreement showed up with products that Tiffany’s management felt were not worthy of the brand name. The jeweler supposedly refused to market and support the sale of the watches, believing that its reputation was more important; that it should mean something if you spend four or five figures on a timepiece with their famous logo engraved on it and they weren’t going to do anything to cheapen the image people have of Tiffany & Company in their mind. As a result, it was found in breach of the agreement with a nearly $500 million pre-tax price tag. Tiffany took the hit and hired Nicola Andreatta, a “third-generation Swiss watch maker” to build an in-house luxury watch business from next to nothing, which you can read about in Fortune. They do not mess around with brand equity, which is one of the reasons the company is so appealing from an ownership perspective; they know the real source of return on capital; the thing that allows them to charge higher prices in addition to higher quality merchandise: Perception.)

And all of that was achieved despite an incredibly painful, high-profile, bitter fight with the Swatch Group that ended in a nearly $300 million after-tax charge to earnings, wiping out almost an entire year of profits. The ruling was reversed on appeal but none of the money has, yet, been returned to the firm. (The situation is complex. If allegations are to be believed, the watchmaking powerhouse with which Tiffany & Company entered a 20-year agreement showed up with products that Tiffany’s management felt were not worthy of the brand name. The jeweler supposedly refused to market and support the sale of the watches, believing that its reputation was more important; that it should mean something if you spend four or five figures on a timepiece with their famous logo engraved on it and they weren’t going to do anything to cheapen the image people have of Tiffany & Company in their mind. As a result, it was found in breach of the agreement with a nearly $500 million pre-tax price tag. Tiffany took the hit and hired Nicola Andreatta, a “third-generation Swiss watch maker” to build an in-house luxury watch business from next to nothing, which you can read about in Fortune. They do not mess around with brand equity, which is one of the reasons the company is so appealing from an ownership perspective; they know the real source of return on capital; the thing that allows them to charge higher prices in addition to higher quality merchandise: Perception.)

It’s a familiar story for owners of the fine jeweler. Consider what a $10,000 investment in the Tiffany & Company IPO would be worth now with dividends reinvested according to the data Tiffany provides on its investor relations calculator.

| DATE | REASON | FACTOR | SHARES | PRICE | VALUE | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 5, 1987 | Initial Investment | 434 | 23.00 | $9,982.00 | 0.00% | |

| Jun 14, 1988 | Dividend | 0.004 | 434 | 37.00 | $16,088.77 | 61.18% |

| Sep 14, 1988 | Dividend | 0.004 | 434 | 37.00 | $16,090.58 | 61.20% |

| Dec 14, 1988 | Dividend | 0.004 | 434 | 40.63 | $17,671.01 | 77.03% |

| Mar 14, 1989 | Dividend | 0.004 | 434 | 41.50 | $18,051.21 | 80.84% |

| Jun 14, 1989 | Dividend | 0.006 | 435 | 56.87 | $24,739.39 | 147.84% |

| Jul 17, 1989 | Dividend | 0.500 | 660 | 42.50 | $28,058.57 | 181.09% |

| Sep 14, 1989 | Dividend | 0.006 | 660 | 54.38 | $35,905.89 | 259.71% |

| Dec 14, 1989 | Dividend | 0.006 | 660 | 47.00 | $31,037.17 | 210.93% |

| Mar 14, 1990 | Dividend | 0.006 | 660 | 42.63 | $28,155.50 | 182.06% |

| Jun 14, 1990 | Dividend | 0.009 | 660 | 45.50 | $30,056.81 | 201.11% |

| Sep 14, 1990 | Dividend | 0.009 | 660 | 33.13 | $21,891.10 | 119.31% |

| Dec 14, 1990 | Dividend | 0.009 | 660 | 39.50 | $26,105.95 | 161.53% |

| Mar 14, 1991 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 46.75 | $30,903.33 | 209.59% |

| Jun 14, 1991 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 54.25 | $35,866.87 | 259.32% |

| Sep 16, 1991 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 50.25 | $33,228.09 | 232.88% |

| Dec 16, 1991 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 46.00 | $30,423.54 | 204.78% |

| Mar 16, 1992 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 48.25 | $31,917.43 | 219.75% |

| Jun 15, 1992 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 32.75 | $21,669.95 | 117.09% |

| Sep 15, 1992 | Dividend | 0.009 | 661 | 27.88 | $18,453.37 | 84.87% |

| Dec 14, 1992 | Dividend | 0.009 | 662 | 27.75 | $18,373.12 | 84.06% |

| Mar 15, 1993 | Dividend | 0.009 | 662 | 28.13 | $18,630.51 | 86.64% |

| Jun 14, 1993 | Dividend | 0.009 | 662 | 28.50 | $18,881.36 | 89.15% |

| Sep 14, 1993 | Dividend | 0.009 | 662 | 28.88 | $19,138.90 | 91.73% |

| Dec 14, 1993 | Dividend | 0.009 | 662 | 34.00 | $22,537.75 | 125.78% |

| Mar 15, 1994 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 31.75 | $21,052.08 | 110.90% |

| Jun 14, 1994 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 35.50 | $23,544.35 | 135.87% |

| Sep 14, 1994 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 37.38 | $24,797.01 | 148.42% |

| Dec 14, 1994 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 40.25 | $26,706.70 | 167.55% |

| Mar 15, 1995 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 30.88 | $20,495.32 | 105.32% |

| Jun 16, 1995 | Dividend | 0.009 | 663 | 35.50 | $23,567.46 | 136.10% |

| Sep 18, 1995 | Dividend | 0.009 | 664 | 42.75 | $28,386.35 | 184.38% |

| Dec 18, 1995 | Dividend | 0.009 | 664 | 51.25 | $34,036.23 | 240.98% |

| Mar 18, 1996 | Dividend | 0.009 | 664 | 53.75 | $35,702.34 | 257.67% |

| Jun 26, 1996 | Dividend | 0.013 | 664 | 69.38 | $46,092.55 | 361.76% |

| Jul 24, 1996 | Stock Split | 1,328 | 32.00 | $42,518.35 | 325.95% | |

| Sep 18, 1996 | Dividend | 0.013 | 1,329 | 39.50 | $52,500.20 | 425.95% |

| Dec 18, 1996 | Dividend | 0.013 | 1,329 | 34.00 | $45,206.66 | 352.88% |

| Mar 18, 1997 | Dividend | 0.013 | 1,330 | 41.00 | $54,530.54 | 446.29% |

| Jun 18, 1997 | Dividend | 0.018 | 1,330 | 47.63 | $63,371.80 | 534.86% |

| Sep 17, 1997 | Dividend | 0.018 | 1,331 | 46.19 | $61,479.16 | 515.90% |

| Dec 18, 1997 | Dividend | 0.018 | 1,331 | 37.06 | $49,350.37 | 394.39% |

| Mar 18, 1998 | Dividend | 0.018 | 1,332 | 49.19 | $65,526.40 | 556.45% |

| Jun 17, 1998 | Dividend | 0.023 | 1,332 | 42.63 | $56,817.74 | 469.20% |

| Sep 17, 1998 | Dividend | 0.023 | 1,333 | 36.81 | $49,090.77 | 391.79% |

| Dec 17, 1998 | Dividend | 0.023 | 1,334 | 41.44 | $55,295.47 | 453.95% |

| Mar 18, 1999 | Dividend | 0.023 | 1,334 | 72.00 | $96,103.23 | 862.77% |

| Jun 21, 1999 | Dividend | 0.120 | 1,337 | 88.38 | $118,166.99 | 1,083.80% |

| Jun 21, 1999 | Dividend | 0.030 | 1,337 | 88.38 | $118,166.99 | 1,083.80% |

| Jul 22, 1999 | Stock Split | 2,674 | 50.88 | $136,056.49 | 1,263.02% | |

| Sep 16, 1999 | Dividend | 0.030 | 2,675 | 60.88 | $162,877.39 | 1,531.71% |

| Dec 16, 1999 | Dividend | 0.030 | 2,676 | 81.69 | $218,632.40 | 2,090.27% |

| Mar 16, 2000 | Dividend | 0.030 | 2,677 | 79.56 | $213,012.02 | 2,033.96% |

| Jun 16, 2000 | Dividend | 0.040 | 2,679 | 62.06 | $166,265.04 | 1,565.65% |

| Jul 21, 2000 | Stock Split | 5,358 | 36.44 | $195,252.91 | 1,856.05% | |

| Sep 18, 2000 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,363 | 39.63 | $212,559.94 | 2,029.43% |

| Dec 18, 2000 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,370 | 30.63 | $164,502.01 | 1,547.99% |

| Mar 16, 2001 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,378 | 28.69 | $154,297.83 | 1,445.76% |

| Jun 18, 2001 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,384 | 33.53 | $180,542.99 | 1,708.69% |

| Sep 18, 2001 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,394 | 22.25 | $120,020.97 | 1,102.37% |

| Dec 18, 2001 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,401 | 28.00 | $151,253.40 | 1,415.26% |

| Mar 18, 2002 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,407 | 37.01 | $200,140.66 | 1,905.02% |

| Jun 18, 2002 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,413 | 37.01 | $200,356.96 | 1,907.18% |

| Sep 18, 2002 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,422 | 25.00 | $135,556.29 | 1,258.01% |

| Dec 18, 2002 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,430 | 25.06 | $136,098.52 | 1,263.44% |

| Mar 18, 2003 | Dividend | 0.040 | 5,439 | 26.20 | $142,506.99 | 1,327.64% |

| Jun 18, 2003 | Dividend | 0.050 | 5,447 | 32.97 | $179,602.32 | 1,699.26% |

| Sep 18, 2003 | Dividend | 0.050 | 5,454 | 39.66 | $216,318.11 | 2,067.08% |

| Dec 17, 2003 | Dividend | 0.050 | 5,460 | 42.81 | $233,771.91 | 2,241.93% |

| Mar 17, 2004 | Dividend | 0.050 | 5,467 | 38.64 | $211,273.89 | 2,016.55% |

| Jun 17, 2004 | Dividend | 0.060 | 5,476 | 37.08 | $203,072.27 | 1,934.38% |

| Sep 16, 2004 | Dividend | 0.060 | 5,486 | 32.06 | $175,908.34 | 1,662.26% |

| Dec 16, 2004 | Dividend | 0.060 | 5,497 | 30.95 | $170,147.15 | 1,604.54% |

| Mar 17, 2005 | Dividend | 0.060 | 5,507 | 31.82 | $175,259.81 | 1,655.76% |

| Jun 16, 2005 | Dividend | 0.080 | 5,521 | 32.92 | $181,759.07 | 1,720.87% |

| Sep 16, 2005 | Dividend | 0.080 | 5,532 | 37.76 | $208,923.55 | 1,993.00% |

| Dec 16, 2005 | Dividend | 0.080 | 5,544 | 39.17 | $217,167.62 | 2,075.59% |

| Mar 16, 2006 | Dividend | 0.080 | 5,555 | 39.10 | $217,223.07 | 2,076.15% |

| Jun 16, 2006 | Dividend | 0.100 | 5,572 | 33.25 | $185,278.50 | 1,756.13% |

| Sep 18, 2006 | Dividend | 0.100 | 5,588 | 33.50 | $187,228.80 | 1,775.66% |

| Dec 18, 2006 | Dividend | 0.100 | 5,603 | 37.89 | $212,323.04 | 2,027.06% |

| Mar 16, 2007 | Dividend | 0.100 | 5,616 | 42.71 | $239,893.10 | 2,303.26% |

| Jun 18, 2007 | Dividend | 0.120 | 5,630 | 48.90 | $275,335.05 | 2,658.32% |

| Sep 18, 2007 | Dividend | 0.150 | 5,646 | 53.95 | $304,614.03 | 2,951.63% |

| Dec 18, 2007 | Dividend | 0.150 | 5,664 | 46.87 | $265,485.66 | 2,559.64% |

| Mar 18, 2008 | Dividend | 0.150 | 5,687 | 36.44 | $207,256.68 | 1,976.30% |

| Jun 18, 2008 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,708 | 46.34 | $264,530.95 | 2,550.08% |

| Sep 18, 2008 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,733 | 38.22 | $219,148.54 | 2,095.44% |

| Dec 18, 2008 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,773 | 24.72 | $142,716.04 | 1,329.73% |

| Mar 18, 2009 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,819 | 21.14 | $123,029.08 | 1,132.51% |

| Jun 18, 2009 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,858 | 25.73 | $150,730.99 | 1,410.03% |

| Sep 17, 2009 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,883 | 38.82 | $228,410.47 | 2,188.22% |

| Dec 17, 2009 | Dividend | 0.170 | 5,907 | 42.41 | $250,533.69 | 2,409.85% |

| Mar 18, 2010 | Dividend | 0.200 | 5,932 | 47.58 | $282,256.54 | 2,727.66% |

| Jun 17, 2010 | Dividend | 0.250 | 5,966 | 43.79 | $261,256.37 | 2,517.27% |

| Sep 16, 2010 | Dividend | 0.250 | 5,999 | 44.42 | $266,506.55 | 2,569.87% |

| Dec 16, 2010 | Dividend | 0.250 | 6,022 | 64.61 | $389,140.36 | 3,798.42% |

| Mar 17, 2011 | Dividend | 0.250 | 6,049 | 56.67 | $342,824.17 | 3,334.42% |

| Jun 16, 2011 | Dividend | 0.290 | 6,073 | 72.71 | $441,612.22 | 4,324.09% |

| Sep 16, 2011 | Dividend | 0.290 | 6,097 | 75.00 | $457,282.13 | 4,481.07% |

| Dec 16, 2011 | Dividend | 0.290 | 6,125 | 62.61 | $383,507.28 | 3,741.99% |

| Mar 16, 2012 | Dividend | 0.290 | 6,151 | 68.03 | $418,482.95 | 4,092.38% |

| Jun 18, 2012 | Dividend | 0.320 | 6,188 | 53.75 | $332,608.75 | 3,232.09% |

| Sep 18, 2012 | Dividend | 0.320 | 6,218 | 64.08 | $398,511.69 | 3,892.30% |

| Dec 18, 2012 | Dividend | 0.320 | 6,252 | 59.87 | $374,319.89 | 3,649.95% |

| Mar 18, 2013 | Dividend | 0.320 | 6,281 | 68.83 | $432,340.41 | 4,231.20% |

| Jun 18, 2013 | Dividend | 0.340 | 6,309 | 76.59 | $483,218.77 | 4,740.90% |

| Sep 18, 2013 | Dividend | 0.340 | 6,335 | 80.29 | $508,707.78 | 4,996.25% |

| Dec 18, 2013 | Dividend | 0.340 | 6,359 | 91.47 | $581,697.12 | 5,727.46% |

| Mar 18, 2014 | Dividend | 0.340 | 6,382 | 92.67 | $591,490.64 | 5,825.57% |

| Jun 18, 2014 | Dividend | 0.380 | 6,407 | 99.90 | $640,063.47 | 6,312.18% |

| Sep 18, 2014 | Dividend | 0.380 | 6,431 | 99.99 | $643,074.78 | 6,342.34% |

| Dec 18, 2014 | Dividend | 0.380 | 6,454 | 103.62 | $668,864.66 | 6,600.71% |

| Mar 18, 2015 | Dividend | 0.380 | 6,483 | 85.45 | $554,030.62 | 5,450.30% |

| Jun 18, 2015 | Dividend | 0.400 | 6,511 | 93.15 | $606,548.45 | 5,976.42% |

| Sep 17, 2015 | Dividend | 0.400 | 6,543 | 80.61 | $527,498.55 | 5,184.50% |

| Dec 17, 2015 | Dividend | 0.400 | 6,579 | 73.23 | $481,822.58 | 4,726.91% |

| Dec 31, 2015 | Current Investment | 6,579 | 76.29 | $501,956.09 | 4,928.61% | |

That chart is demonstrative of a key concept I try to reiterate all the time: If you have a good business, with real profits, and you pay a reasonable price relative to those earnings, it eventually shows up in your net worth. Add diversification to make up for any “breakage” (e.g., you get bought out during a market collapse and thus lose the opportunity to participate in recovery) you realize how simple the whole thing is. It would have been a mistake to try and buy and sell Tiffany & Company rapidly, trading its shares as if they were cheap baubles. As the earnings kept marching toward the sun, you should have guarded them, refusing to part ways no matter what the stock market was doing at the time precisely as you would if you’d owned 100% of the place. There was a 5-year period in the late 1980s and early 1990s when the shares collapsed by 50%, the same way shares of The Hershey Company do from time to time. Trying to avoid this sort of thing is a fool’s errand. It’s a waste of energy if you managed to get the purchase price right.

An even more extreme illustration: Your shares were worth $213,012.02 in March of 2000 at the height of the dot-com bubble and, nine long years later, a mere $123,029.08 at the depth of the Great Recession. Nearly a decade of waiting had resulted in 42.2% losses. Of course, you could have mitigated these were you dollar cost averaging your way into more ownership over time, the highs and lows averaging each other out nicely to some degree, but that pain on paper was still very, very real. Let the magnitude sink in for a moment. Nine years for 42.2% losses on paper. The culprit: Extreme levels of overvaluation at the start of the period. On 1999 earnings of $1.95 per share, the stock was going for $79.56. It was an earnings yield of 2.45% compared to the 10-year Treasury yield of 6.26% that same day. In other words, for taking practically no risk and parking your money in the sovereign debt of the United States, you were guaranteed a base return of at 256% more money. With the valuation multiple already elevated to extremely high levels, Tiffany & Company would have had to grow to the moon in a short span of time to be fairly appraised at that price.

An even more extreme illustration: Your shares were worth $213,012.02 in March of 2000 at the height of the dot-com bubble and, nine long years later, a mere $123,029.08 at the depth of the Great Recession. Nearly a decade of waiting had resulted in 42.2% losses. Of course, you could have mitigated these were you dollar cost averaging your way into more ownership over time, the highs and lows averaging each other out nicely to some degree, but that pain on paper was still very, very real. Let the magnitude sink in for a moment. Nine years for 42.2% losses on paper. The culprit: Extreme levels of overvaluation at the start of the period. On 1999 earnings of $1.95 per share, the stock was going for $79.56. It was an earnings yield of 2.45% compared to the 10-year Treasury yield of 6.26% that same day. In other words, for taking practically no risk and parking your money in the sovereign debt of the United States, you were guaranteed a base return of at 256% more money. With the valuation multiple already elevated to extremely high levels, Tiffany & Company would have had to grow to the moon in a short span of time to be fairly appraised at that price.

Here we are, 29 years after that IPO and none of it mattered because mean reversion relative to intrinsic value cannot be escaped indefinitely. Despite those horrifically painful periods, you’ve compounded your money at an incredible 14.4%+ per annum; from a firm that everyone, their mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, great, great grandmother, and great, great great grandmother knows. Even better, the ending multiple relative to growth is sane. A strong argument can be made that the shares are much more reasonably valued for a long-term owner at today’s price, even if we were to go into a recession tomorrow. In our case, that’s not merely an academic opinion. Aaron and I, along with members of our family, have picked up shares for our own long-term portfolios recently, though I’d start to get really serious about it compared to everything else on my desk if it were to get down into the $50’s or lower. If you discover the shares at 50¢ on the dollar a few years from now, don’t cry for us. We’re almost assuredly still sitting on our equity and, all else equal, probably writing more checks.

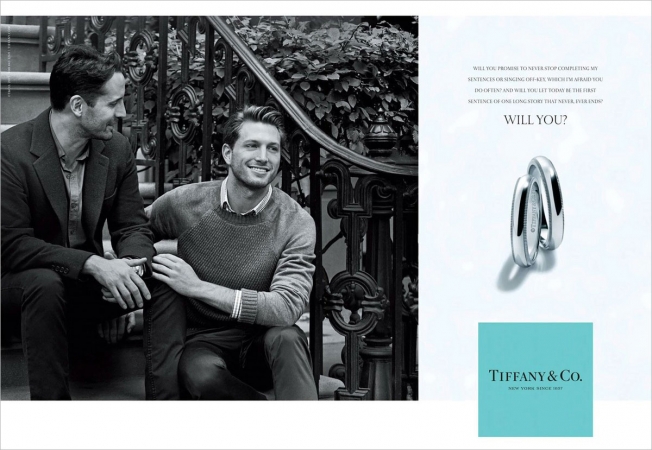

Tiffany & Company was one of the first jewelers in the United States to celebrate marriage equality, launching an advertising campaign around a real-life couple in its home market of New York City. If you go into the Kansas City boutique today, there’s a section featuring men’s rings with that couple’s picture prominently displayed next to them. It meant a lot to Aaron and me, both as shareholders and customers (our own wedding rings are from Tiffany).

Why am I telling you all of this? To remind you of something that doesn’t receive enough focus in universities, on the Internet, or during face-to-face conversations among investors: The price you pay ultimately matters a great deal more than almost any other variable (the return on capital employed by the underlying business being a close second – if you’re dealing with a top-shelf asset, a bit of overvaluation is probably not going to make much difference in the long-run). There is a price so high, if you pay it, you’re screwed. To a point (presently ignoring things like environmental liabilities or other exposures that could cause something to have a negative value, turning it into a liability), no matter how bad the asset is, there is a price so low that, if you pay it, you could have a good outcome. The moment you write the check and your transaction is recorded, the die is cast. There’s no going back because that is the relative point against which everything else will be measured. The same company, the same assets, the same employees, the same profits; different purchase price, wildly different outcomes result based on that purchase price. The old retail adage, “Well bought is well sold” is particularly appropriate. Make a list of the generational holdings you want to acquire and then watch them like a sniper lining up a target. It may take years, perhaps even a decade or more, but sooner or later, you very well may get your price.

Is Tiffany & Company a steal? No. But I wouldn’t think it a mathematically foolish suggestion that a 1% to 3% portfolio weighting, acquired at today’s prices, held with dividends reinvested and ignored for the next 25 years, has a higher-than average probability of a satisfactory outcome that would cause the owner to look back with a lot of joy and fondness on the decision. It’s a far different situation than four years ago when the earnings and growth projections didn’t justify the price. Once attained, extreme passivity seems the most intelligent course of action. While I can’t offer any guarantees, I’m willing to wager that if you get back to me in January of 2041, assuming we’re both still fortunate enough to be alive, you’ll see that I was right.

*Update: Sometimes, you really do get a burst of good luck seemingly out of nowhere. Within 72 hours of publishing this, fortune began smiling upon value investors as the Chinese implosion caused equity prices to tank. In the contagion, Tiffany & Company shares fell another ~10%, hitting a new 52-week low. I had two family members pick up shares earlier today (Friday, January 8th, 2016), both paying in the $60s. As I mentioned in this post, I keep hoping we see the $50s or lower (stranger things have happened; back during the 2009 period we discussed, there was an ephemeral moment when the shares hit the high teens) because it would cause me to seriously look at making a substantial commitment given what I’d be receiving relative to the core economic engine. Nevertheless, it’s foolish to put off what I consider a demonstrably fair long-term purchase today for the hope of an extremely favorable, less probable price tomorrow. When and if that cheaper price ever arrives, I’ll take advantage of it from cash flow and cash reserves. If it does materialize, whether or not I mention our activities on this blog, you can probably guess what I’ve been doing if you spot me walking around Kansas City humming “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend”.