Vanguard Accused of Dodging Nearly $35 Billion in Taxes – Expense Ratios May Need to Quadruple According to Expert Report Submitted to IRS

Please note that as a result of the conversations and questions in the comment thread, I reorganized, rewrote, and significantly expanded this post on Sunday, December 6th, 2015 at 2:20 p.m. If you read it prior to this time, you may want to re-read it because it is a far different piece that gets into the specifics of transfer-pricing regulations and potential outcomes for existing investors in Vanguard for the sake of providing greater clarity to those who want to understand the mechanics of the tax dodge / abuse allegations.

From August 2008 to June 2013, David Danon was an associate attorney in the tax department at the Vanguard Group. According to a whistleblower lawsuit filed with the State of New York, which served as the basis for additional whistleblower actions filed with the State of Texas, the State of California, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Internal Revenue Service, Danon was silenced, and ultimately sent packing, after he persistently warned management that Vanguard was committing a massive tax dodge by using a combination of legal entities and improper pricing structure; an arrangement that went back 40 years. Danon claims that others who had raised similar concerns had also left the firm after facing a backlash for refusing to toe the line on what they believed was illegal behavior.

According to the whistleblower documents (you can read the complaint in PDF here), this alleged tax dodge is one of the key reasons that Vanguard can offer drastically below-average expense ratios. Aside from threatening the very existence of Vanguard’s business as it currently operates, it could also open the door to claims of on-going violation of anti-trust regulations meant to ensure fairness in the marketplace should competitors and regulators smell blood in the water.

Is any of it true? I have no idea. It’s definitely something to at least keep on your radar with major news outlets now reporting on it. For now, let’s look at what the accusations are given the information that has been released to the public so we can attempt to make sense of them.

To Understand the Accusations Against Vanguard, You Must Understand the Basics of Transfer-Pricing Tax Law

First, let’s step back and discuss what Vanguard is accused of doing.

In the United States, we operate using a hybrid form of regulated free market capitalism. We do this because laissez-faire capitalism doesn’t work unless you have certain reset mechanisms in place that keep things fair for consumers and competitors; that avoid monopolistic abuses; prohibit industry collusion; stop us from becoming a landed aristocracy in which, after a generation or three of successful individuals accumulating resources, it becomes impossible for others to enjoy upward mobility based on effort due to all of the levers of power and capital becoming concentrated in the hands of a few operators, investors, and/or their heirs that can then erect barriers to entry that make it practically impossible for upstarts to flourish.

There are all sorts of ways we achieve this as a civilization. For example, your local power company must, by definition, almost always be a monopoly because otherwise it wouldn’t be economical. Why build two multi-billion dollar power plants when only one will do? We, as a country, don’t want bankrupt facilities of that magnitude and danger being run on a shoestring budget so, instead, we established rate boards of citizens and specialists who guarantee the utility companies certain minimum profit levels in exchange for hitting service metrics. We establish gift taxes and estate tax limits and exemptions so those who didn’t earn their wealth can’t inherit ungodly amounts of power and influence without restraint. We denote certain transportation facilities and technological infrastructure as “common carrier”, taking away the ability of the operators to discriminate against customers. We establish civil rights laws and rulings that prohibit discrimination based upon certain personal characteristics.

Comparably, one of the protections we have in place is that a business must charge a fair price for its products or services. Here, there are two areas that often get confused:

- Consumer and Competitor Protections – Things such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) using its authority, including under laws such as the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act that arose during the Gilded Age when monopolies threatened to take over certain industries and undo many of the benefits of free market capitalism, to ban predatory or below-cost pricing (you can’t just charge whatever you want for a product or service, especially if the goal is to gain market share and drive competitors out of business), forbid manufacturers, distributors, and retailers from tying the sale of two products together under certain situations, restrict certain exclusive supply or purchase agreements, prevent mergers and acquisitions that could lead to effective control of an industry, and punish those who engage in so-called “Refusal to Deal” violations (e.g., if you own the town newspaper, you can’t refuse to carry ads for the town radio because they are a competitor).

- Tax Protections – These are rules governing the way profitability is calculated, and the formulas that must be used, in order to prevent a firm from cheating the civilization of the tax revenue it is rightfully owed; tax revenue that provides the military that protects its corporate assets, the infrastructure that makes it possible for workers to show up in the morning; benefits such as limited liability against employees, operators, and investors if things go south.

At the moment, Vanguard is being accused of violating the second part of those protections – the tax rules (if that turns out to be the case, it very well could open it up to claims of the first type of violation). Specifically, the whistleblower appears to be claiming that Vanguard has committed an on-going 40 year tax dodge involving something known as transfer-pricing.

It is an esoteric area of tax law that is vitally important now that we live in a world of multi-nationals. Transfer-pricing regulations benefit every citizen. These rules prevent a company such as Starbucks from setting up a foreign affiliate that owns the licensing rights to the Starbucks name then charging the U.S. operations licensing fees to the point it has no remaining profits to be taxed. This is accomplished by establishing minimum profitability guidelines and rules that must be followed when entering into transactions between controlled affiliates.

Typically, when dealing with a controlled affiliate, a firm must follow transfer-pricing rules such as those found in 26 CFR 1.482-5 – Comparable profits method. In essence, and grossly oversimplifying the calculation (there are a handful of approaches and variables that also can be used including the so-called “cost plus method” and “profit split method”), a company is required, by law, to charge its affiliates the closest comparable market rates excluding its own operations when setting its prices. In other words, it must deal with its own controlled affiliate based on a calculation that most closely approximates the prices it would have to pay if it were an arms-length, third-party transaction with an independent contractor. The accounting and auditing techniques to ensure this has been done properly includes tools such as the Berry ratio, which analyzes gross margin divided by operating expenses.

To give you an idea of the scope of transfer-pricing, a quick reference guide created by leading accounting firm PWC for tax year 2013/2014 covered almost 900 pages. Go take a look at it yourself in the source PDF. It governs everything from setting prices on affiliate loans to selling equipment from one subsidiary to another. Again, these rules help prevent someone with a pen and a lot of time from playing the game in a way that you and I have to pick up their costs while leveling the playing field in other ways. Without them, you could simply set up a firm in Ireland, have it “loan” all of the money you use in your domestic operation at an extraordinarily high interest rate, and then suck the effective profit out via interest on the loans, leaving the manufacturing business at break-even while enjoying the profits, earned in the United States, that have now been transferred overseas. (It is a very different thing from another area we have discussed in the past, which is legitimately earned foreign taxes, which have already been subject to taxation after being earned within that foreign jurisdiction, being unfairly targeted for taxation, again.)

Agree with it or disagree with it, those are the rules. While it may occasionally lead to some regulatory headache, it’s an otherwise rational approach to protect the integrity of the free markets by keeping certain firms from gaining unfair cost advantages and protecting the taxpayer from certain firms abusing the rules to lower or eliminate their tax bill, sticking everybody else with higher costs.

What Is Vanguard Accused of Doing?

Whatever internal documents Vanguard’s former tax attorney turned over as part of the whistleblower case purport to show that the mutual fund giant has 1.) failed to follow the required standards that must be used in transfer-pricing transactions for the calculation of taxable profit, and 2.) used multiple legal entities to artificially deflate its remaining earnings (tied to a $1.5 billion contingency reserve that has made headlines) in an effort to reduce effective would-be taxable profit further so it pays the government practically nothing. If true, this would result in the firm itself having an enormous, immoral market advantage as it would be mathematically impossible for it to set its fees at their current rates were they not committing tax abuse as well as allowing Vanguard investors to steal from the rest of society, sticking everybody else with a bill that they should have had to pay. These advantages, over long periods of time, would have been responsible for it taking over much of the industry. The whistleblower claims that employees who discovered the specifics of the alleged abuse, and brought it up to management, were silenced or laid off.

In essence – and, again, I’m going to need to oversimplify it here given the complexity of transfer-pricing rules – Vanguard is accused of point-blank refusing to follow the tax laws for the sake of lowering fees for its owners, who, if true, would now be enriched by the tax dodge. Under the tax law, it appears as if its affiliates should have been charging the mutual fund and index funds under its management market average rates. This would have caused substantial income tax to be owed on the money that was legitimately earned within the United States as well as forced it to compete more fairly with other asset management companies such as Fidelity and Schwab, which are presumably following the rules and being put at a disadvantage because of it.

Following the tax laws would not have been incompatible with Vanguard’s mission to provide lower-than-average costs because Vanguard is owned by its investors rather than outside stockholders. That means it could have opted to distribute some of those higher accounting earnings to investors in the form of dividends, somewhat akin (the legal, accounting, and tax parallels aren’t appropriate but from a practical economic standpoint, you’ll see the similarities) to a mutually owned insurance company paying a dividend to its policyholders or a co-op paying a dividend to its members. That is, if you held a lot of money in something like a Vanguard S&P 500 index fund, had Vanguard been ethically behaving in compliance with the law, your expense ratio might have been substantially higher but you would have been sent a big dividend check for your pro-rata share of the Vanguard profits in your capacity as an owner. It wouldn’t have been as large as the current proceeds received from the alleged tax abuse but it would have still been substantial.

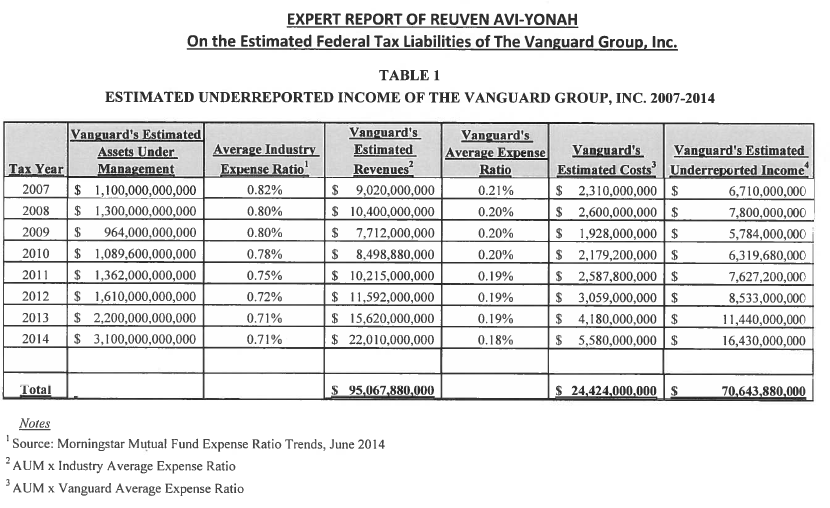

Expert Report on the Vanguard Tax Allegations for the Past 8 Years Alone Put Underreported Profits at Nearly $71 Billion with Taxpayers Shafted by Almost $35 Billion

To support his claim and estimate the potential tax dodge (remember that, in no small part due to the abuses, coverups, and frauds of the past quarter-century, Congress passed laws allowing whistleblowers to share in any recovered money, rewarding them for potentially ruining their career and social life as well as incentivizing them for bringing tax cheats to light), the former Vanguard tax attorney-turned-whistleblower went to a respected international tax expert, Dr. Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, the Irwin I. Cohn Professor of Law and Director of International Tax LLM Program at the University of Michigan, asking him to prepare a report for the IRS and SEC.

Before we get into the findings of the report, to give you an idea of the academic’s credentials, which demonstrates the reason his opinion carries so much weight in this field, here are some of the highlights from his University of Michigan biography page. He:

- Has served as a consultant to the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on tax competition

- Is a member of the steering group for OECD’s International Network for Tax Research.

- Is a trustee of the American Tax Policy Institute

- Is a member of the American Law Institute,

- Is a fellow of the American Bar Foundation

- Is a fellow of the American College of Tax Counsel,

- Is an international research fellow at Oxford University’s Centre for Business Taxation.

- Has taught at Harvard University (Law)

- Has taught at Boston College (history)

- Practiced law with Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy in New York; with Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz in New York; and with Ropes & Gray in Boston.

- After receiving his BA, summa cum laude, from Hebrew University, he earned three additional degrees from Harvard University: an AM in history, a PhD in history, and a JD, magna cum laude, from Harvard Law School.

- Has published more than 150 books and articles, including Advanced Introduction to International Tax (Elgar, 2015), Global Perspectives on Income Taxation Law (Oxford University Press, 2011), and International Tax as International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

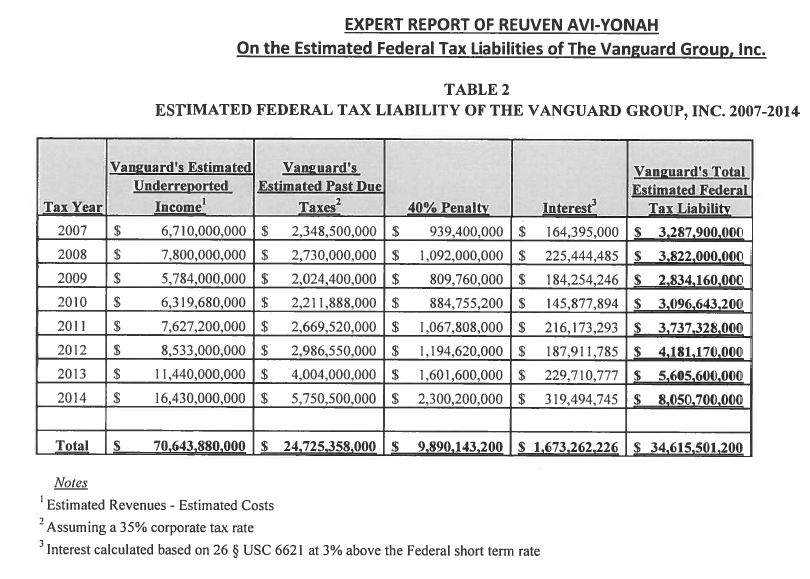

The report is damning. (In case you want to read it for yourself, I have made a PDF version available to download here for your convenience.) Dr. Avi-Yonah conservatively estimates that Vanguard owes nearly $35 billion in back taxes, penalties, and interest for the past eight years alone (I could be mistaken – I need to check a regulation before stating this to be fact – but I believe the report limits the total tax bill to this period because the statute of limitations had run out on the alleged violations that might have occurred in the previous 30+ years so there was no point in going back further as it was inconsequential to the issue of what would be owed today were Vanguard held accountable).

In fact, in his opinion, the transfer-pricing tax violations are so evident to him that he pulls no punches and outright, unequivocally states, “If the IRS were to pursue this matter, it will prevail in court” (emphasis added).

Specifically, Dr. Avi-Yonah’s calculations indicate that, at a very minimum, Vanguard should be charging expense ratios of 0.71% to 0.82% on its internal fund management arrangements under the transfer pricing rules. (Whether you are agree with or disagree with the transfer pricing tax regulations is inconsequential on this point. There are rules for the calculations and Vanguard is being accused of simply refusing to abide by them because it doesn’t feel like it. That isn’t how the rule of law works. You can’t walk into an electronics store, steal a television off the wall, and then go home and brag about how it was moral because of all the money you saved your family members.)

Even still, the IRS might find that the 0.71% to 0.82% is a conservative estimate because the rules require the use of industry-wide expense ratios which have been driven down, in no small part, due to the need to compete with Vanguard’s artificially compressed price structure made possible by the alleged tax abuse. In other words, if Vanguard hadn’t been supposedly cheating in the first place, expense ratios wouldn’t have been that low and would need to be increased. Nevertheless, even with the conservative estimate, between 2007 and 2014, Dr. Avi-Yonah calculates for the SEC and IRS that Vanguard underreported its profit by a jaw-dropping $70,643,880,000. With past due penalties and interest, this represents an unpaid tax liability of $34,615,501,200.

Startled by the enormity of the charges, journalists who have been looking into the case have been seeking comment from other experts. One reporter, Joseph N. DiStefano, took the findings to another tax specialist, Robert Willens, whom he called “a prominent New York business tax attorney”. (That’s an understatement. Willens has been named one of the one hundred most influential CPAs in the country, serves as an adjunct professor of finance and economics at Benjamin Graham’s alma mater, Columbia University, was the chairman of the committee on revision of corporate tax laws for the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, has published several tomes on corporate taxation, and remains a sought after specialist for complex tax situations in corporate America.)

DiStefano recounted Willens comments as, “”It seems like a pretty clear-cut case,” “I know Vanguard says they have meritorious defenses and special circumstances that might excuse them. But the principle in law is that they have to deal with their funds at arm’s length,” and the funds must pay Vanguard’s management company fees as if they were paying an independent contractor, not a special low price”. Willens went on to say that he doesn’t think the IRS will be inclined to use its power to put Vanguard out of business, but instead, seek a settlement that would cause Vanguard’s expense ratios to “absolutely” rise. [Source]

What Does This Mean for Vanguard’s Investors?

It appears to me that Vanguard’s response to the allegations was to declare war on the whistleblower. From what I can tell, it sent its lawyers to court and all but said that what they were doing wouldn’t have been uncovered if their tax-attorney-turned-whistleblower hadn’t been so disgusted by the alleged abuse that he broke the attorney-client privilege. (In other words, had he been a tax accountant, who isn’t bound by confidentiality rules, it could proceed to trial but because he was a tax attorney, he wasn’t allowed to speak about the things he learned.) Using this technicality, Vanguard got his lawsuit thrown out of court, avoiding having to go to trial; a trial which would have been high-profile and involved watching its internal documents on full display for the world to scrutinize. However, the judge made a point of saying “she wasn’t ruling on the merits of Danon’s allegations and that her actions didn’t affect the state’s ability to pursue them”. He is appealing. [Source].

Unfortunately for Vanguard, the New York outcome doesn’t do them any good with the potential SEC and IRS investigations, either or both of which could have far-reaching ramifications for the firm as well as the financial markets. It also doesn’t do them any good in the other states. Texas paid Danon $117,000 as a confidential informant after Vanguard agreed recently to pay millions of dollars in back taxes as part of some other situation that has not been fully disclosed. The California case is still pending.

Broadly speaking, I think there are five potential outcomes entirely aside from the issue of back taxes that may or may not be owed:

- No Wrong-Doing Is Discovered and the Status Quo Remains: Vanguard might be found to have done nothing wrong by any of the regulators and courts that have it under its microscope. I strongly hope this is the case because I have so much admiration for John Bogle and what he has done. At the moment, however, the reaction of the firm, and the findings of an expert who is among the best in the world at his discipline as well as other esteemed tax specialists who have looked at the documents, does not give me a lot of optimism.

- A New Type of Non-Profit Exemption Is Created: Vanguard might be able to use its influence and power to get what I consider to be a moral exception written into the law to make it comparable to a mutually owned insurance company such as State Farm or Liberty Mutual (the two largest property and casualty underwriters in the United States). To do this, it would need to add a 30th exemption to the 501(c) statutes that covered asset management operations. It would begin charging reasonable expense ratios to its funds but then it would start paying a dividend to Vanguard investors (who are also the owners) for their share of the pro-rata (now higher and taxed) earnings. The dividend could come in the form of cash or, if it wanted, additional shares of the underlying index funds or mutual funds depending on how it was structured. Vanguard keeps its low-cost advantage despite some absolute rise in costs, Vanguard investors begin enjoying regular dividends from their ownership stake the same way mutually owned insurance companies do, and there is no more immoral or unethical behavior happening as is alleged in the whistleblower claims.

- Politicians Are Bought and Unfair Advantages Remain: Vanguard might be able to use its influence and power to get what I consider to be an immoral exception written into the law to protect its own interest the same way the sugar lobby (and one family down in Florida, particularly) has been able to artificially control cane sugar due to buying politicians and regulators. The investors of Vanguard will continue to benefit from expense ratios that they now know come from cheating their fellow citizens.

- Demutualization and Vanguard Investors (Potentially) Getting Rich: Vanguard decides to demutualize like the waive seen at the end of the 20th century when some of the biggest insurance companies became joint stock corporations and sponsored IPOs. Shares would be allocated to existing Vanguard investors based on a formula that included their relative percentage of assets under management. It would still be possible to keep the place a low-cost operator like Amazon, CostCo, or Wal-Mart due to the corporate culture explicitly stating, perhaps in some sort of Credo akin to the one used by Johnson & Johnson, that their objective is for [x]% of assets under management to be in the bottom [x]% of industry-wide fees. Long-term Vanguard investors who happened to be in before the demutualization might be paying a lot more but their added costs could be dwarfed by the shares they received in the IPO. It could be life altering for people who suddenly found themselves drowning in wealth they never expected. In other words, it very well might turn some long-term Vanguard investors into millionaires overnight.

- Wipeout: The IRS or another regulator agency effectively puts Vanguard out of business. (While it could happen if there is a Teddy Roosevelt working in one of those agencies, I think it is extremely unlikely. There’s no reason to Arthur Anderson the thing.)

I don’t think #4 can happen while John Bogle is alive, even though he no longer runs the firm, because I get the impression his whole ego is wrapped up in the place to the detriment of his rationality, he’s written about his distaste for publicly traded asset management companies in the past, and he still represents an important figurehead decades after he was pushed out of top management due to his age in a high-profile rift. He has enough sway with Vanguard’s existing investors that he could present a major roadblock should he use the power of his pen to criticize any demutualization plan. Would he be successful? I don’t know. Waive enough money in front of people’s faces and they might take it. (If you were a long-time Vanguard investor and suddenly found out that by voting “yes”, you’d receive a block of stock in the upcoming IPO – maybe tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in free shares deposited into your brokerage account – would you refuse? Not many people would.)

Even if a demutualized Vanguard achieved the same ultimate mission, I think he’s become obsessed with form over function and couldn’t accept it. I can’t see him adapting like Charlie Munger when the Savings and Loan industry became too revolting for him, resigning in a very high profile way back in the 1980’s because it was no longer compatible with his analysis of the right way to behave. Munger will sacrifice his ego for the optimal. He’d tear down his favorite institution or idea if it was proven incapable of living up to his standards. He’d throw out his life’s work if he found a better strategy or construct. As good a man as Bogle appears to be, I’m not sure he can. I think he loves Vanguard in that special way only an entrepreneur will understand and part of that is the legal structure to which it has become wedded.

It’s Going To Be Interesting To See the Cognitive Gymnastics That Occur Throughout the Financial Industry on the Vanguard Allegations

In fact, I’m really interested to see Bogle’s reaction. I think he will swear, and perhaps even believe deep down in his heart, that Vanguard has done nothing wrong. Unless I’ve been totally duped all this time, I truly think he is a man of integrity who wouldn’t knowingly break the law. I’d almost have to conclude, absent other evidence, that he became so obsessed with his mission of low costs that he went down a wrong path to achieve it, succumbing to a temptation that even he warned against in one of his essays (“… recent years have shown us that when ambitious chief executives set aggressive financial objectives, they place the achievement of those objectives above all else – even above proper accounting principles and a sound balance sheet, even above their corporate character. Far too often, all means available – again, fair or foul – are harnessed to justify the ends. [snip] “Management by measurement” is easily taken too far.” See Don’t Count on It! The Perils of Numeracy: Peril #4: The Adverse Real-World Consequences of Counting, Sub-Section: Counting at the Firm Level).

There are some things in Bogle’s recent writings that have given me … pause … to the point that I’ve privately discussed with Aaron my belief that he may no longer be totally objective; not like he was in his earlier days, with his legacy now entirely wrapped up in the overly simplified message that fees are all that count even to the point of rejection of some of the justifications that behavioral economics indicates are relevant. For example, there was a passage in one of his recent books that I thought was more than a little intellectually dishonest; something that would have been unthinkable decades ago. I hate even mentioning it because of my enormous respect for the man – I think in many ways he embodies the concept of “a life well lived” where you contribute to the civilization and serve others – but I think he’s allowed his own “best loved idea”, to borrow a Mungarism as we were just discussing him, to influence his message in a way that is not always positive. This particular passage bothered me because Bogle is a brilliant, Princeton-educated economist who spent his lifetime in asset management where he demonstrated unimpeachable integrity. He was making a point using a particular mathematical relationship that he had have known was not indicative of economic reality due to changes in payout structure and tax laws, but that supported his message on cost. It bothered me so much, I can still remember where I was sitting when I read it. I could understand someone else making the error in good faith but there is little chance he could. It’s beneath him. He is too smart to have to resort to trickery to attempt to convince people of his thesis. In a lot of ways, I think Bogle was, and is, doing the equivalent of “The Lord’s Work” in capital markets so I hold him to a higher standard. Perhaps it’s not fair of me to do so.*

On the flip side, I think you’re going to see some competitors react with glee, perhaps even to the point of distastefulness, if the allegations turn out to be true. For some of these competitors, I have to say: You can’t really blame them. Imagine you were running your business ethically and honestly. You pay your taxes, follow the rules, and compete year after year, decade after decade. They keep beating you on cost but, it turns out, they’ve been lying on their tax return and don’t have this enormous tax bill you do because they are dishonest. Finally watching them get caught, and knowing that their prices are going to have to rise to give you some relief, is a very human reaction. As the experts who have looked at this have conceded, unless Vanguard is found totally innocent or buys its way into an exemption by bribing lawmakers, there is a not-insignificent probability that Vanguard’s expense ratios go up by 400% to around 0.80%. It’s still objectively very cheap and, if combined with either a newly implemented investor/owner dividend or a demutualization as previously discussed, would be far less painful that it sounds at first glance, but it provides more breathing room for Fidelity, Schwab, American Century, and the rest.

I’ve been asked about my thoughts, particularly, given that we are in the process of launching a global asset management company. (I think you are wise to ask these questions; that they are very intelligent because, at least on the surface, it appears that it could introduce a conflict of interest.) To be as blunt as I can about it, and risk offending a few people because I’m going to have to get into issues of socioeconomic status, I don’t think it has any meaningful effect on us either way. Ultimately, you’ll have to answer that for yourself but upon even a cursory examination, it’s a fundamentally different business, focusing on fundamentally different types of clients, providing a fundamentally different experience and menu. Vanguard could quite literally charge 0% per annum on its assets and it wouldn’t have any effect on the compensation system we plan to employ anymore than the availability of free trading at Loyal3 has any effect on what Julius Bär does. The people coming to us do not, and will not, care what Vanguard charges. Vanguard has built an enormous empire appealing to mom and pop investors with relatively small median account balances who have fairly straightforward financial needs. (The firm is somewhat tight-lipped on its entire client base but they do release information on defined contribution retirement plans, of which they are one of the biggest providers. To be specific, in 2014, according to Vanguard’s own numbers, the median participating balance for a retirement account held at the firm was $29,603 [Source PDF, page 5, printed], down from $31,396 in 2013 [Source PDF]. Still, it’s grown nicely since the market bottom in 2009 when the median Vanguard retirement account balance was only $23,140 [Source PDF, page 36, printed number]. Median, as you’ll recall, is the point at which half are above and half are below. In contrast, our expected minimum required account size, absent case-by-case exemptions, is set at $500,000 in investable assets.) The people coming to us, asking to have us invest their money alongside our own, are disproportionately highly successful, often financially sophisticated, individuals and their families. They are fully aware they can buy an index fund, they are fully aware of what the costs will be at the time the paperwork is signed, and in many cases, they have far different needs, objectives, and risks than a typical household, making cost but one variable in an overall decision they’ve reflected upon and made.

In actuality, I find what is happening at Vanguard more than a bit disheartening. It only adds to the ambivalence I’ve felt about it in recent years. In the decade-and-a-half since John Bogle left, there is an arrogance coming out of the firm, especially now that its market share has reached 20%, that could be its downfall. I mean, management forced beneficiary changes on 170,000 client accounts to make their own internal paperwork easier; beneficiary designations that supersede a person’s existing will / estate plans and effectively disinherited who knows how many people. (They now require you to have identical beneficiaries on all identical IRA types, which is an utterly idiotic policy that does nothing but serve their own best interest at the expense of the client.) Still, they’re so much better than many of their competitors, I find myself somewhat uncomfortable criticizing them. If you have, say, $25,000 in savings, you’re not going to find many better options out there if you’re satisfied with the limited range of choices they offer.

Footnotes

*I’ve been asked in the comments about the specifics of the passage. I may try to provide an updated link here in the future.