A Look at Laugh-O-Gram Films, the Business Walt Disney Bankrupted

In the past week, we’ve talked about the phenomenal success of an investor who bought shares of Walt Disney Productions (now called The Walt Disney Company), a decision that would have turned a 1,000 share position costing $13,880 into somewhere between $26,672,640 and $40,000,000 between 1957 and 2013. We even looked inside the secret family holding company, WED Enterprises, Walt Disney used to build his own family’s wealth and retain power. Most people don’t know that before those two firms, there was another that changed the direction of Walt Disney’s life. It did not enjoy a fairy tale ending but it did lay the foundation for the things that came much later.

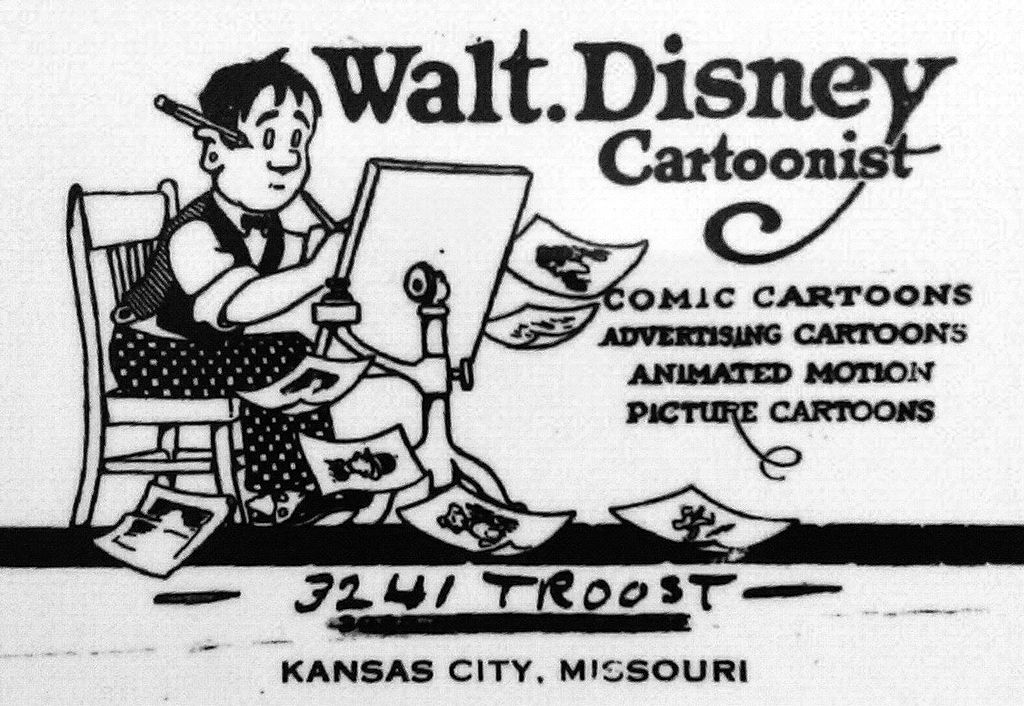

At 20 years old, Walt Disney decided to fill out the forms with the Missouri Secretary of State to launch a new company. He called it Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc. The articles of association were signed on May 18th, and the State of Missouri issued a certificate of incorporation on May 23rd, 1921. Disney had no real money, but he figured the best way to start was to raise cash from other people so he could focus on what he loved.

At 20 years old, Walt Disney decided to fill out the forms with the Missouri Secretary of State to launch a new company. He called it Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc. The articles of association were signed on May 18th, and the State of Missouri issued a certificate of incorporation on May 23rd, 1921. Disney had no real money, but he figured the best way to start was to raise cash from other people so he could focus on what he loved.

Walt had Laugh-O-Gram Films issue 300 shares of stock at $50 each, resulting in a $15,000 initial capitalization. In inflation adjusted dollars, that is $203,000 today. Disney contributed equipment, cash, and intellectual assets to keep 70 of these shares for himself, with the other 230 shares going to friends, employees, and outside investors, the most prominent of whom was a surgeon named Thomas Pendergast.

Thomas Pendergast came from the hometown in which I was raised, St. Joseph, Missouri, which was also home to the Tootle-Lemon Bank. Pendergast moved to Kansas City, became a well known investor, and counted among his patients President Harry Truman. Thomas began his involvement with young Disney’s new enterprise by purchasing $2,500 worth of shares in Laugh-O-Gram, which is around $33,860 in inflation-adjusted terms. He later served as an emergency lifeline for loans and other working capital needs when the ship began to sink. This was a man who had powerful connections, liked helping out young upstarts, and built a collection of businesses and stocks that made him one of the richest people in the Midwest, all while continuing his day job as a doctor.

(An interesting aside: A few years after the period we are discussing, Pendergast constructed a mansion at 5650 Ward Parkway, which happens to be on the market right now for just shy of $4,000,000.)

Walt, in his capacity as President of Laugh-O-Gram, had the firm rent an office at 1127 East 31st Street, in Kansas City, Missouri. He hired employees and began his very first animation studio, brimmed full of excitement and expectation at the fortune and fame that he was certain lay just around the corner. He had suffered setbacks in the past – a camera and a Model T he owned had been repossessed due to non-payment, and a fruit manufacturer in which his father had invested nearly all of his childhood savings had gone bankrupt – but he knew it was going to work out this time.

The Laugh-O-Gram building in Kansas City in August of 2010, taken by Iknowthegoods and made available under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. It is located at 1127 East 31st Street.

Shortly after incorporation, the manager he hired signed a contract with the Pictorial Clubs, Inc., a distributor for schools and churches, that was horribly structured. Laugh-O-Grams promised six animated shorts, delivered no later than January 1st, 1924. For this, Disney was to receive $11,000, but only $100 was due at the time of signing, so Laugh-O-Grams had to take on all of the expense and working capital of the project; funding that it didn’t have. Almost immediately after the ink dried on the contract, Pictorial Clubs went bankrupt, and the people who seized its assets demanded that Laugh-O-Grams keep up with its end of the bargain by delivering the films that could not possibly be finished. Along with a few other mistakes, it was less than two years until Disney found himself evicted from, or sneaking out of, at least three offices in the middle of the night, being chased down by processors for the courts for non-payment of bills, starving as he was unable to afford food and had tapped out all his available sources of credit, and alone, as his family moved away from Kansas City for Oregon or California.

The debts mounted, the employees resigned as their paychecks kept bouncing, and twenty four months later, Disney was standing in Union Station, crying, watching trains leave the city hoping he could get on one. He was a high school dropout, in his early twenties, had no income, no assets, had ruined his reputation among the investors in the region, had no family and few friends surrounding him, bankrupt, with a few shabby articles of clothing, one pair of shoes, and no money to eat.

Disney went door-to-door, raising money for a ticket as a photographer, offering to take pictures of children and families. He finally got his hands on enough cash, boarded the train, and moved to Hollywood with nothing; an absolute failure at this point.

Ten years later, he sent money back to the creditors, repaying the amounts that he owed even though they had been discharged in bankruptcy.

One famous story goes that during those late nights when he was all alone, sleeping on the couch at the office because he couldn’t afford rent, there were tame mice that was always scrounging around the wastepaper basket. He put them in wire cages at his desk, and grew close to one of them that he kept on his drawing board. It was that mouse, which he sat free when he left for California, that served as the inspiration for Mickey Mouse. Of course, given Disney’s history, it was almost certainly made up as he knew part of the magic was in the telling of the fable.

If you want to read more about how it all happened, check out Neal Gabler’s book Walt Disney: The Triumph of The American Imagination.