Don’t Let Wall Street Analysts Do All Of Your Thinking For You

Generally speaking, it’s a very bad idea to rely on Wall Street analysts to make decisions for you when it comes to your investment portfolio. Often, people who work on Wall Street display a strong bias toward overoptimism when it comes to future results, while neglecting the stable, boring companies at fair prices. (It is somewhat amusing that we tend to be in a period where this has been reversed – it’s the boring, dividend paying companies that have been driven up to prices too high to justify as income investors, starved for yield, chase anything that provides some cash flow.)

There is an element of human nature, but I tend to believe a lot of it comes down to the incentive system in place at most financial institutions. I’ll paraphrase one famous investment author, who wisely asked, “What do you think would happen if the textile analyst came into the meeting for an entire year and said, ‘There are no textile companies worth buying? My recommendation is you do nothing.'” Before long, they would be out of work, even though they were doing the right thing for the firm.

Let me back up for a minute and explain what made me think about this. I haven’t been around much this week because I’m working on finalizing our tax filings for 2012 (the partnership returns are due by September 16th, and my personal returns by mid-October). The accounting firm had settled nearly everything, so I had to go through them, check the numbers, and sign off on the returns before they were shipped off to the Federal, state, and local governments. Then, I turned my attention to the technology project I’m working on, as a sub-set of the minimalism project. I’m going through 12+ years of digital archives, destroying what is no longer valuable and organizing, tagging, and sorting the rest into the new server. This has been an on-going thing I’ve been working on for some time and have mentioned. This morning, I came across some of my old investment notes and files from 2005.

Back then, I was shortly out of college, armed with a six-figure household income and no job, focusing on my first e-commerce site with Aaron (a letterman jacket company), and spending my days reading as many 10Ks as I could to provide a foundation of knowledge that I thought might be helpful in my own businesses and later in life, when I went to buy other peoples’ businesses in entirety. I was obsessed with a handful of corporations, which I’ve talked about many times in the past so there is no use rehashing the discussion here, except to illustrate this over-reliance on analysts. Instead, I want to remind you that often, your best ideas are not going to be applauded at the time they are made. I spent the entirety of this period buying as much AutoZone, Direct General, Yankee Candle, and Berkshire Hathaway as I could because I could look at the accounting and tell that I was getting more value than I paid for at the current market prices. The “popular” stocks that everyone was chasing just wouldn’t work in my calculations, no matter how many times I ran the numbers.

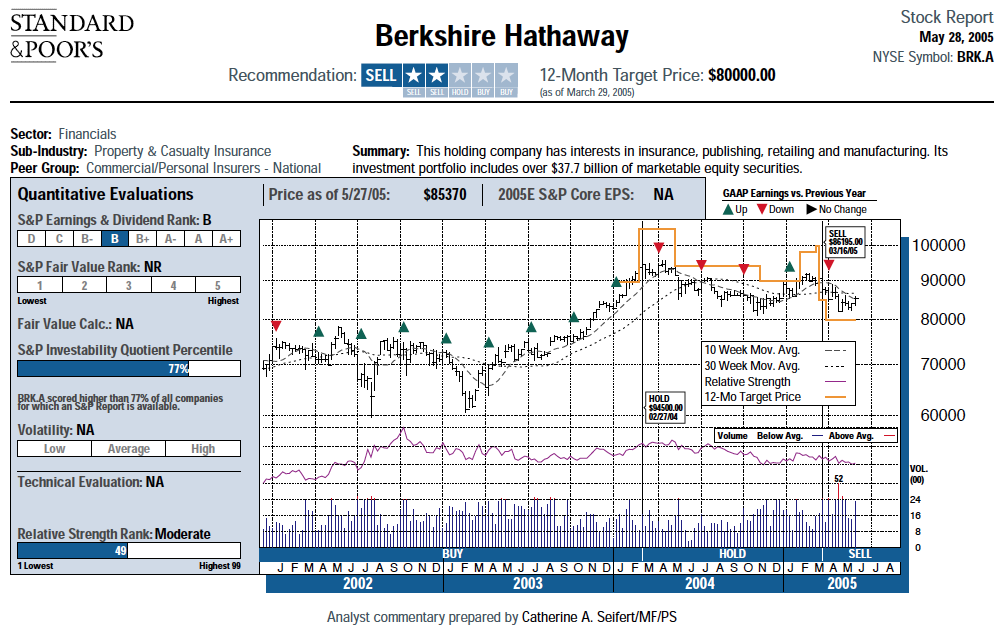

Consider Berkshire Hathaway. It was one of the largest, most profitable, most diversified, well-run conglomerates on the entire planet. It had two of the most famous investors at its helm, and was trading at a reasonable price based on the current holdings, with no consideration given to the money that would inevitably be generated as the billions of dollars in profit were kicked up to headquarters and redeployed into more businesses. The Class A shares were selling for $85,370 at the time, making the now-split-adjusted Class B shares the equivalent of $56.91. Was it a steal? No. But it was fair. It was what you had a right to expect from such a lumbering behemoth. You exchanged a good price for an ownership stake in a collection of assets that promised to drown you in cash year after year, and which you got to ignore the rest of the time.

Yet, Standard and Poor’s thought it was boring. They believed the company was too highly valued, offered no compelling opportunities, and was just sort of … there. S&P’s analyst did something very rare among the people who write about securities and issued a “Sell” rating on the stock. This means, effectively, that they were telling even those with large deferred tax float tied up in their low cost basis shares that it was time to jump ship.

The price to earnings ratio on Berkshire Hathaway appeared to be 21.9 times S&P’s estimated core earnings. But it wasn’t, had they calculated core earnings correctly. A quick analysis of the valuation method I prefer makes evident the reason: True, owner earnings were substantially higher than what the income statement alone would indicate, a fact that was obfuscated by a myriad of factors including the use of the cost accounting method for tens of billions of dollars in equity stakes in other, highly profitable firms, large insurance operations with conservative accounting policies, and long-term subsidiaries carried at a fraction of their current market value on the balance sheet. That means the true valuation multiple was substantially lower than would first appear to be the case picking up the newspaper or browsing through stock quotes.

In 2005, S&P was recommending investors sell their ownership stake in Berkshire Hathaway because it appeared that short-term sales were going to decline. The Class A shares were then at $85,370 each, making the now-split-adjusted Class B shares $56.91.

This notion that a long-term investor without a need for liquidity should sell his or her stake was, frankly, idiotic. Anyone could read the annual report. Anyone could see that the firm was much more likely to be earning substantially more 5 or 10 years in the future. Anyone could see the price was approximately reasonable, trading at around intrinsic value. The difference came from temperament. Getting rich over time wasn’t good enough – it never is when there is easy money around, and it was not difficult to get your hands on funds in those days.

Not only did I not listen to S&P’s analyst, I decided that she was dead wrong and bought shares, all of which still happily sit in the joint brokerage account my husband and I use for our legacy positions. Today, the Class A and Class B shares trade for $167,565.00 and $111.86, respectively. While this isn’t shoot-the-lights-out performance, over the past 8 years, it’s been a port in the maelstrom as the entire world faced a global recession that was the worst thing since the Great Depression, half of Wall Street seemed to disappear, unemployment reached the double-digits (and remains there for some sub-demographics of society), record numbers of Americans lost their homes to foreclosure, and the stock market collapsed by 50% then recovered several years later. Meanwhile, you at least doubled your money as you didn’t have to worry about the nightmare everyone else was facing.

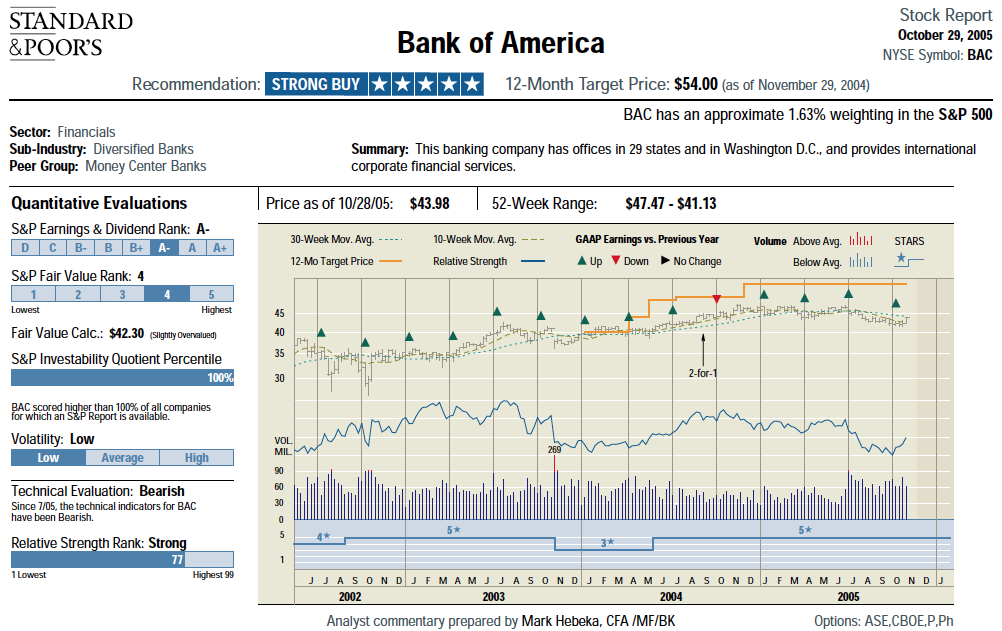

What was S&P telling you to buy back in 2005? Not just buy, but “Strong Buy”? Bank of America. The bank appeared to be selling for 10.2 times core earnings – or less than half of what Berkshire Hathaway was. Once again, it was an illusion. Bank accounting rules are notorious in that they cause a bank to look safest when the danger is highest (when the economy is doing its best and then starts to slow, reserves are at an all-time low; when the economy is doing its worst and then starts to recover, reserves are at an all-time high). Meanwhile, everyone was talking about how easy debt had made home prices rise far above the median household income in many metro markets, charge-offs were far below historical averages, and there were television and shows devoted to flipping houses. It was no secret, to anyone who had any sort of knowledge of financial history, that there was a credit bubble. The handwringing about it went on for years before it suddenly burst. This was not something that snuck up on anyone who was paying attention.

At the same time, S&P was recommending a “strong buy” for Bank of America, at a time when the economy was at a high (bank earnings are notoriously cyclical), there were some incredibly questionable things going on in the accounting, in my opinion, and the valuation was not that compelling looking 5 to 10 years out in the future.

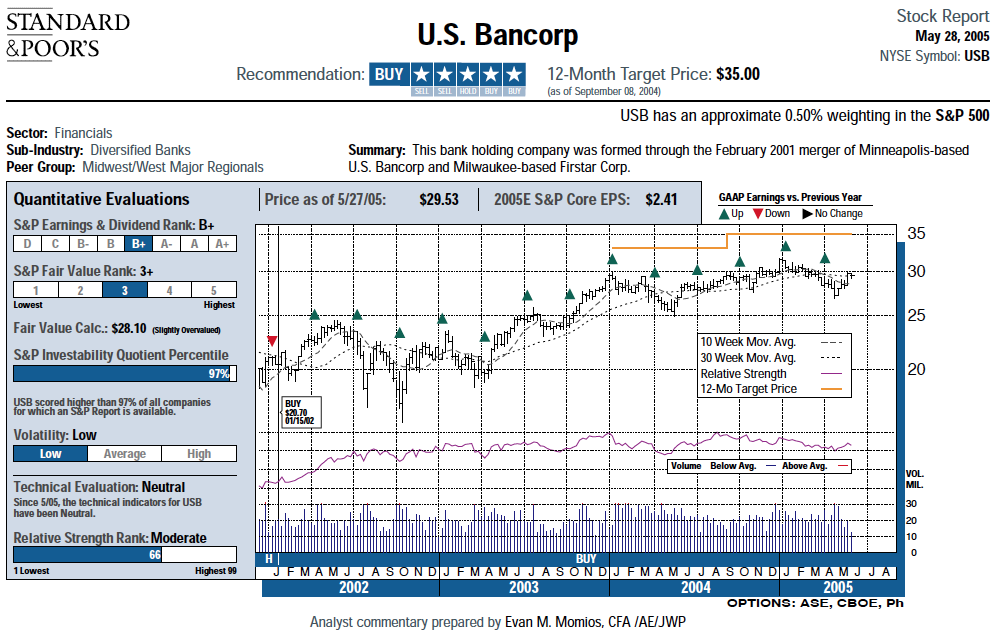

I did buy a bank during this period – U.S. Bancorp (a few years later, during the crisis, I also bought shares of Wells Fargo for dirt cheap once it had gotten its hands on Wachovia). S&P rated U.S. Bancorp lower than Bank of America back in 2005, at only a “Buy”, because U.S. Bancorp looked more expensive at 12.2x core S&P earnings, and a 4.1% dividend yield. Again, this was a case of appearances being deceiving. Was U.S. Bancorp valued more highly than Bank of America? Yes, slightly. But not when you got to the “risk-adjusted” park I’m constantly harping on when I write about this stuff.

My reasoning for preferring it, and picking up some shares that still sit in one of my personal IRAs to this day, came down to the reality behind the financial numbers on the spreadsheet. Despite somewhat similar surface-looking figures, the difference in corporate culture between the two banks was enormous. U.S. Bancorp was boring. It liked being boring. The CEO collected more from his dividends on the common stock he had built up over his career than he did in salary, which told me this was a place that had its priorities right. The entire focus was on plain vanilla lending and fee-based products such as credit cards. The success was measured by how much of that could be returned to owners in the form of dividend income, and how much excess capital the bank had above and beyond what regulators considered safe. I knew, from the people around me and my own experience, that you could walk into a bank and get free money almost anywhere, but U.S. Bancorp still wanted to see two years of tax returns, verify your assets, and run you through the hoops to make sure you actually had the goods. It was like the smart girl at the prom; she may not be the most glamorous at the moment, but you know she’s going to just get better and better with age. A few decades later, people will look at her, with her high performing career, comfortable income, nice car, and great wardrobe and wonder how it happened. By the time they come to appreciate her, it’s too late.

U.S. Bancorp was treated as an also-ran among the major banks, ignored compared to many of its larger, and more glamorous, competitors.

Bank of America, or its management, rather, had an inferiority complex. They wanted to be respected on Wall Street. It wasn’t good enough to make billions of dollars from old-fashioned banking. They made things far too complex, the accounting was much too obfuscated, and they didn’t have nearly a strong enough cultural obsession with returning surplus earnings to owners as should be the case for a large bank that can’t put the cash to good use.

Here, again, I concluded that the S&P analyst was wrong. I didn’t want Bank of America. I didn’t care that it looked cheap. I didn’t care that the dividend yield was 4.5%. The entire thing gave me the same creepy feeling you get when you see swamp water – you can’t be certain what is below the surface. The best course of action is to avoid swimming in places where you might turn out to be lunch.

Bank of America was a disaster for its owners. Your $43.98 stock is now trading at $14.36, so you lost $29.62 along the way. Some of this was made up for by $7.45 in cash dividends, which served as a sort of rebate on your purchase price. Thus, your net loss turned out to be $22.17 per share, or 50.4%. You have waited patiently for 8 years and your reward was to lose half of your money, plus the remaining half is going to buy you less due to nearly a decade of inflation.

While the core bank does have some share of the blame, it ended up coming down to management’s obsession with breaking into the New York investment business that ultimately spelled doom in the long-run. The former CEO stepped in to acquire Merrill Lynch instead of sticking to its core banking function, paying nearly full price instead of pennies on the dollars, which he could have gotten had he waited a few days. (Ironically, this mistake probably ended up saving the entire global financial system as it prevented the destruction of yet another major investment bank following Lehman Brothers).

Over that same period, the “boring” U.S. Bancorp, which also went through the worst banking crisis in generations, has increased your wealth by just shy of 50%, coming in the form of $6.94 in capital gains and $7.75 in cash dividends, totaling $14.69 in profit on the original cost of $29.53 as of the report date from S&P’s analyst. (My personal holdings did a bit better because I paid roughly 10% lower than the price published at the time the S&P analyst released his report.)

In other words, $100,000 in Bank of America is now worth $49,600. The same $100,000 in U.S. Bancorp is now worth $149,746. The analysts were not factoring in the safety of the income and assets; focusing instead, on short-term profits and extrapolating that the past would always be like the future. Banking melt downs are among the most common and predictable events in history, so this was particularly unfortunate. I don’t think it is an accident that you didn’t see these same mistakes being made by many, if any, of the folks who lived through the Savings & Loan crisis of the late 1980’s and early 1990’s.

Sometimes, Analysts Ignore the Obvious Conclusions Despite Getting the Numbers Right

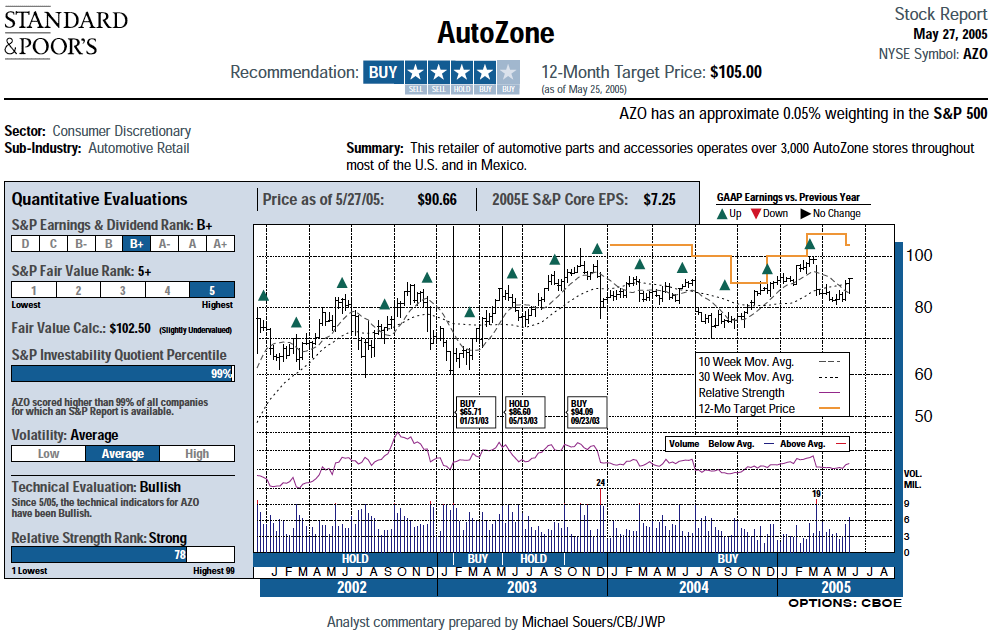

Back in May of 2005, shares of AutoZone were $90.66 each. Today, they are $417.53. This was the business that, during a very big chunk of my early career, was the only thing I talked about, the only thing I cared about, and the only thing I focused on buying. I first noticed it several years prior, when the outstanding shares began dropping like a rock and management drastically reduced the amount of working capital necessary to fund the business, which influenced the valuation formula I use. Here, the analyst got most of it right, but ignored the obvious conclusion.

The intrinsic value calculation performed by S&P assumed a terminal growth rate of 3%. The problem with this approach was that it is one of those numbers thrown around in business school without a lot of thought. It was the wrong number to use.

The firm was trading at 8.6x estimated core S&P earnings. I agreed with this assessment. Furthermore, the firm had taken to a policy of paying no dividends, and waiting for the shares to return at least 10% based on market price, at which point it would go into the market and buy back very large blocks of its own stock, destroying it to reduce the outstanding share count. You had this situation where average weighted shares outstanding had fallen from 152,090,000 in 1998 to 79,630,000 the prior fiscal year 2004. If the stock wasn’t cheap, it would sit on the cash and wait. When it was cheap, the company would buy back as much as possible.

Not only did you have a market leading retailer that was somewhat recessionary proof (it does better in bad economic conditions because people try to hang on to their cars longer, repairing and maintaining rather than replacing and discarding), and not only was it going to enjoy some low digit organic growth from store expansion and price increases year after year, but you had to factor in that the terminal growth rate was going to be much higher than otherwise expected because all of the earnings were getting put back into the firm in a sort of on-going buyout process where the selling stockholders were exiting what amounted to a public partnership, in spirit. The question came down to, “What is the earnings yield going to be on the average repurchase price?” as this couldn’t be projected with any degree of accuracy. However, if you were wrong, and the stock price rose too quickly, you could always sell, pocketing any profit. At the time, the shares had an earnings yield of nearly 12%, and it was expected earnings per share would keep increasing. Even better, there is a quirk in GAAP rules that require the weighted average shares outstanding to be used in the EPS figure, meaning that for a firm rapidly buying back their own stock, there is always a lagging effect causing the reported EPS to be lower than they will be in a future period with identical net profits. In the case of AutoZone, this was substantial.

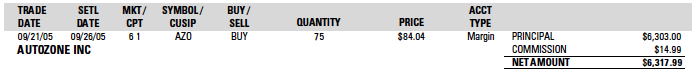

So you had this perfect enterprise, with a recession resistant business, a large network of stores, actual honest-to-God real estate backing the balance sheet, trading at 8x expected earnings, using all excess profit to repurchase shares at a 12% earnings yield, with reported profits understated as a result of the lagging effect of the accounting rules. There was no bad story here. There was no disaster, or poor management. It was just neglected. I had never seen anything like it, so I became almost religious in my zeal for doing whatever I could to pick up more ownership. I have piles of documents that show nothing but this kind of activity:

Shortly after my 23rd birthday, I bought myself another batch of shares as a sort of “gift to me” … At this price, I calculated a greater than 90% probability of compounding at 15% per annum for the next decade. I kept on buying like this through the end of October, every time I made a new deposit from my business profits and copyright royalties.

I kept buying, week after week, in trades just like this, with my lowest price coming in at $79.54 per share and my highest price $92.17 per share. I’m staring at spreadsheets right now that include my valuation for the auto parts retailer.

The analyst got all of this right. What was not accounted for in the report from S&P was the fact that the firm was likely to continue compounding at a very high rate due to this behavior for year after year, until someone finally caught onto what was happening. That means that, yes, the business might be trading at a slight discount to intrinsic value, but that intrinsic value per share was going to increase at a very rapid clip for the next 3-5 years, meaning it was like jumping onto a speeding car on the highway. Intrinsic value is not a stable figure. It’s often better to buy a company trading at a 10% discount to an intrinsic value expanding at 15% per annum than it is to buy a company trading at a 20% discount to an intrinsic value expanding at 3% per annum.

(Some of you will now jump to the conclusion that this is a tautology given that the intrinsic value figure should include the differentiation in growth and discount rates. I won’t say anything more, because I don’t want to talk too much about my process, especially after skimming the surface of it a few days ago. I will say that I believe, strongly, the investors who use a stable discount rate for all assets, rather than attempting to come up with asset-specific discount rates based on perceived risk, are likely to make fewer mistakes and come to more accurate conclusions. If an asset is dangerous enough to warrant a high discount rate, it shouldn’t be on your consideration list in the first place unless you are in a specialty field such as private equity or purchasing distressed debt on a diversified basis. You also know I have a preference for calculating the stable cash extraction value of an asset base over a given period of time. Those of you who are more mathematically dexterous will be able to work out some of the details, and implications, but I’m not going to discuss them any further. That is not the point of this post.)

The moral of all of this is: Read all the research you can. Pay attention to what the analysts say. But make your own decision in the end. You have to have the experience, judgment, and rationality to know when your conclusion is superior to that of someone else, and when you are out of your element. I stayed within a very narrow range of things I understood at the time, stuck with it, then expanded my circle of competence slowly.

You cannot outsource your thinking. You have to be responsible for making the decisions in your life. This is not just limited to investing. It should be that way in your choice of career, your choice of spouse, your choice of living location, your choice of friends. Be aware of what you are doing, why you are doing it, and willing to own mistakes when you miscalculate. Life is so much more enjoyable when you live it fully awake. If you have the structure right, the inevitable mistakes shouldn’t derail you. Truth be told, I actually look back sort of fondly on the lessons I learned from what I consider to be the one dumb thing I did in the past decade as, I imagine, the lessons will save me far more in the future. I will never again discount the transformative role technology in an industry that is undergoing rapid change and has high operating leverage in the form of fixed costs.