Nestlé Dividend Day 2016

Whether you own the shares directly in Switzerland and collect Swiss Francs or indirectly through the American Depository Receipts and collect U.S. dollars, the once-a-year dividend has now been paid by Nestlé to its shareholders with both dates having now past (or, in the case of the latter, arrived). For fiscal year 2015, the board continued its long tradition of dividend hikes and increased the per share rate to 2.25 CHF, up from 2.20 CHF the year prior, representing an increase of 2.27%; a shining achievement for a company so large in a nation where the central bank has imposed negative interest rates on commercial banks and for a business that, last year, was considered such a safe haven that its bonds actually were selling at negative yields as investors flocked to them, which I mentioned in passing on the post about the folly of investing in 50 to 100 year bonds, considering them a better alternative than cash. (Remember, you have to measure nominal changes in currency relative to inflation. Purchasing power is what counts.)

For American holders of the Nestlé ADR who deal with the currency translation complexities, it looks as if the post-translation dividend worked out to $2.3198 per share, out of which you then had to pay a $0.025 per share currency translation and administration fee to Citibank and a $0.348 dividend withholding tax to the Swiss Government (assuming you did your job and made sure your broker filed the correct paperwork entitling you to the benefits of the U.S.-Swiss tax treaty so the 35% rate wasn’t withheld. Every year, I get messages from a handful of people asking why their dividend taxes were more than double what they should have paid. Unless you’re planning on flying to Switzerland to reclaim the funds, make sure to take care of these details).

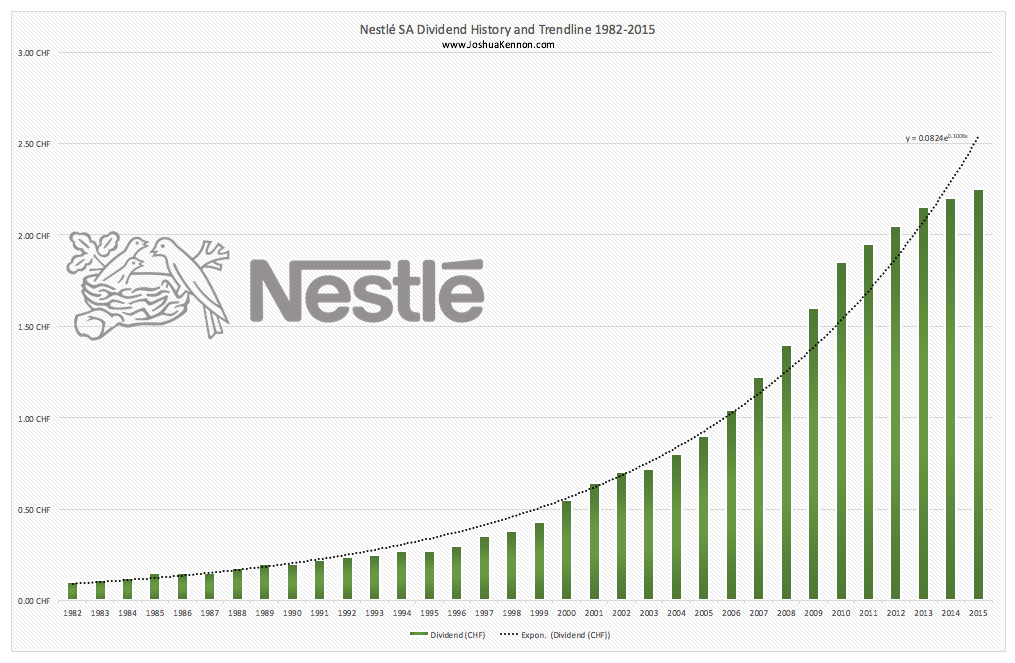

For the decade ended, the dividend increased from 1.04 CHF to 2.25 CHF, representing a 116.3% increase on a per share basis over the initial dividend and assuming no dividend reinvestment on the part of the owner. That approximates a compound annual growth rate in the dividend of 8% per annum through one of the worst economic decades in generations, inclusive of the near total collapse of the global economy between 2008 and 2009. Just as beautifully, during this same decade, Nestlé substantially shrunk its overall shares outstanding while maintaining its sterling balance sheet. Look at the period right before the world fell off a cliff in 2008. The total shares outstanding were roughly 3,615,600,000. Today, that figure is around 3,085,000,000. Despite those rising dividend payments, each share now represents an additional 14.7% ownership in the firm compared to what it did in the year President Obama was elected to office. That prudent use of capital should continue paying off for long-term owners for decades, even generations, in the future.

With the newest data points, this means I can update my long-term Nestlé records. To give you an idea of how it has done since I’ve been alive, if you bought shares around the time I was born back in the early 1980s, you would have collected 0.10 CHF shortly thereafter (I was born in the latter part of the year so you wouldn’t have had to wait much to get that initial, base payout and it therefore doesn’t represent a compounding period). Following the dividend increases over the subsequent 33 years that came after that base rate, your dividend would have grown to the present 2.25 CHF, representing a 2,150% increase over the base rate on a per share basis, assuming no dividend reinvestment on the part of the owner. That approximates a compound annual growth rate in the dividend of 9.9% per annum. This was achieved over a period of war and peace, inflation and deflation, and stock market booms and busts.

It is the fascinating mathematical paradox we discussed in an older post I wrote about Nestlé … that it never looked like the best investment to buy in any particular year but it almost always ended up being one of the best investments you could buy over long periods of time. It has been a money printing machine. It doesn’t even make the radar of a lot of people due to the fact it is traded in Zurich. Those who do notice it often by-pass it because it looks so boring on paper; a quintessential “get rich slowly” stock. It remains the sort of asset that only predominately wealthy families, pension funds, and highly passive international blue chip funds buy and hold. Yet, decade after decade, prices were increased with inflation, competitors were acquired, share count was reduced, dividends per share were increased and owners were showered in piles of money. When new businesses were acquired, the aforementioned sterling balance sheet allowed the firm to lower the overall cost of capital, its purchasing power allowed it to achieve economies of scales that could hardly be matched, and its deep bench of managerial talent allowed it to spread best practices among subsidiaries.

It is proof, yet again, of a saying from global wealth management: “When the going gets tough, the tough buy Nestlé.” It is almost impossible for a member of Western Civilization to go a meaningful length of time without somehow, directly or indirectly, putting money in Nestlé’s pocket. From baby food to frozen pizza, tea to coffee, pasta to confectionery treats, chocolate to cereal, the often overlooked global blue chip has a diversified stream of earnings that allow it survive under nearly any economic or reasonably probable political conditions. Were you to shatter it, many of the subsidiaries in and of themselves would instantly be among the world’s largest food and beverage companies.

One of the new focuses for the business going forward is food-and-beverage-as-a-delivery-mechanism-for-pharmaceuticals. It will take years, if not decades, to materialize but according to The Wall Street Journal‘s story on April 12, 2016, the Swiss titan has been working on prescription medications that will be tailored to the genetic profile of customers. This is thanks to a research and development program internally that was given $500 million to develop medical foods for people with chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, and intestinal disorders. Imagine the profitability if they can do things like develop food that gives folks with Crohn’s Disease relief from their symptoms. They’re striking strategic deals with pharmaceutical companies to develop “amino acid-based products to treat muscle loss”. It’s in anticipation of an aging global population; to go where the money is and create products people don’t even realize they need or demand, yet.

Part of my love for Nestlé is what it reveals about human nature. If you’re a typical American shareholder, you probably own the ADR. You can’t trade options on it. You can’t borrow against it on margin. You have to pay cash for it, in full, and then receive a single, annual dividend payout like you might at a private family business. The stock price sometimes goes sideways for years as people neglect it and the intrinsic value grows internally along with the payouts. Its accounting is conservative. Its returns on capital are far higher than they appear at first glance if you’re just doing quick calculations imported from a finance portal. If you’re 20 or 30 years old, and have a reasonable chance at a 50+ year run in front of you, I’d argue that any halfway intelligent person would consider buying some from time to time, locking it away, and almost never selling it; holding it no as a sort of economic oak tree meant to be left for old age or future generations. Present known factors considered, the numbers seem to indicate that it offers a high probability of satisfactory returns over the next 25 years.