The great thing about making decisions in life through the lens of decision trees and opportunity cost is that it allows you to focus on what you actually want. You tend to protect yourself against giving up what you really want for what you want right now. Everything in life has an opportunity cost. It doesn’t matter how young or old, rich or poor, successful or miserable you are. Opportunity cost is everywhere. At this particular moment, I am facing a situation that involves cars. It’s a perfect example of how those tools – decision trees and opportunity cost – can make choices easier, or at the very least, clearer.

Cars Are Terrible Financial Investments

First, I have a love-hate relationship with cars. The average American spends way too much on his or her car. I hate cars as a financial asset. It angers me that the standard American family has two vehicles, constituting the second largest asset on their balance sheet behind a primary residence. Cars lose value through depreciation. They require maintenance. They must be insured. They need fuel. Worse, they often require interest payments to a bank unless you write a check to cover the entire purchase price, which few families do. Thus, for a typical teenager, cars serve as a rite of passage into the indoctrination of the pay-as-you-go-easy-finance cult. Buying a car is like compounding in reverse. You end up poorer. The more you spend, the more you lose.

On the other hand, there is utility that can be gained from a vehicle. This is especially true if you are in a position to write a check for a car, have more than enough money set aside to grow for the future, and generally like automobiles. Years ago, the first car I bought myself was a Jaguar. I calculated exactly how many shares of stock I would be foregoing to pay for it and there has not been a single moment when I thought, “I wish I had invested the money, instead.” It’s been a great car. I’ve driven it throughout the United States, in all sorts of conditions, and very rarely been disappointed except for the fact that even the smallest repair seems to reach into the thousands of dollars. Likewise, Aaron loved his first luxury car, which was a brand new black Lexus. Even though both were enormously expensive in terms of future compounding given up, they were worth every penny.

Unfortunately, I find myself in the situation of now having to make a decision about cars. Mine needs some work. It is fairly extensive, which would require a decent sized check to fix. I could get it overhauled and still drive it another three to five years. That seems like too much hassle so I looked into getting something new. That way, I can just have the dealership take the existing car off my hands and get a trade-in credit for it. Plus, at this point, it is seven or eight years old and I wouldn’t be opposed to getting something with more bells and whistles as technology upgrades have now made significant advances.

Create a Baseline Against Which to Compare Your Options

To begin, I did some research and started with what I want, without consideration for the money involved. In terms of styling, the car I most like is the Mercedes M class of crossover vehicles. I calculated what it would take if I wrote a check for one, traded in the existing Jaguar, and drove it for 5 to 8 years, owning it outright. This is the baseline. This is the standard against which everything else is now compared.

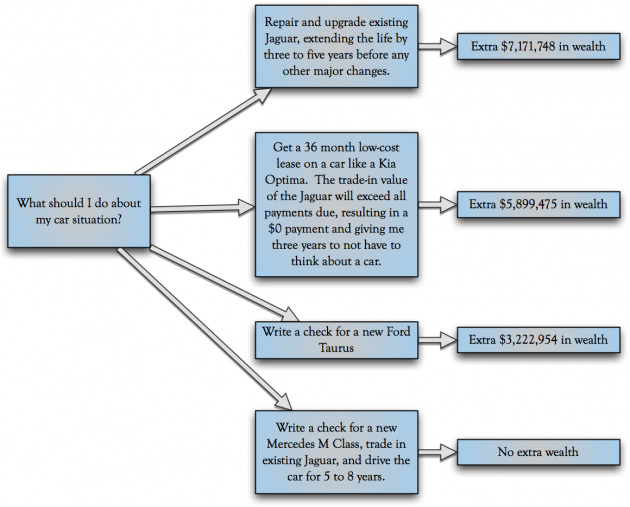

Then, I ran through a series of other scenarios. Here is a small sampling (click the image of the decision tree below to enlarge). The far right of the chart shows the extra net worth I would have by selecting that option instead of the base option, the Mercedes M class. For example, if I decided to write a check for a Ford Taurus, I would have an extra $3,222,954 by the time I reached my golden years by investing the difference between it and what I would have spent in the base scenario, assuming average rates of return and reinvestment of all dividends.

The reason this decision tree is so basic is because I have already taken some possibilities off the table. I could have even more money if I sold the Jaguar, bought a 20-year-old Neon, invested the difference, and ran around town with my bumper hanging off but that isn’t going to happen. Likewise, I love the Bentley Continentals but it would be idiotic for me to give up the kind of future compounding that would be required to own, insure, and maintain a care like that given my age. The two extremes thrown out left me with a decent range of options that seem reasonable to me.

Buying a Car Decision Tree. Consider that over a lifetime, you probably own half a dozen or more cars and it quickly becomes evident how big of an influence your driving habits have on your pocketbook.

To help improve my thinking, I sometimes frame the situation backwards. I use Benjamin Graham’s Mr. Market, asking myself, “If he walked in the door today, and said, ‘Joshua, I will pay you an extra $5,899,475 by retirement to drive a Kia Optima today rather than a Mercedes M crossover'”, would I accept those terms? What matters more to me, the nicer car or more money for myself, my family, my heirs, and my charitable foundation? It comes down to priorities. I can afford either scenario so what matters is what I value. What do I value more?

I know I harp on this a lot but there is no right or wrong answer. Whatever you (or in this case, I) decide to do is entirely about maximizing personal happiness. What, in other words, is going to bring me the most joy? The baseline scenario now or an extra $3.2 million, $5.899 million, or $7.17 million later?

Your Opportunity Cost Will Fluctuate Throughout Your Life

Over time, your calculus will change. Early in life, the opportunity cost of buying nice things was so high that, as many of you know, Aaron drove a 1993 Ford Escort that had hundreds of thousands of miles on it, no heating or air conditioning, and shook when he went above 65 miles per hour on the highway. Today, he wouldn’t consider that an option because 1.) he has less time to compound since he is a decade older, and 2.) he is much richer so the burden of buying a particular item is lower in an absolute, as well as relative, sense.

In my case, if I were 45 years old, this wouldn’t have even made it to the decision tree stage. I would have just bought the Mercedes M class because the future value of compounding wouldn’t have been worth the trade-off for me. The thing is, I am not 45 years old. I am 29 years old. This is why it is important you understand that opportunity cost is personal. If differs for every person. It will differ you at various times in your life.

Why do many people fail at their financial goals? They focus on the now. They say, “Sure, I can afford it easily” instead of, “Would I rather have [x]?”. That shift in your outlook can radically transform your life. Whether you are choosing a college, thinking about switching careers, starting a business, or buying a block of stock, always focus on the trade-offs; the opportunity cost of your decision.

To the extent matters can be controlled, your are the architect of your own financial destiny. When you buy a car, or even a television, you are making a multi-million dollar decision whether you realize it or not. The culmination of those decisions will help determine where you end up in life.

Footnote: I should point out that other factors come into play when buying a car, since that is the example we used in this discussion of opportunity cost and decision trees. If I were a young lawyer, financially successful, launching my own practice, I would buy an extremely nice car because of signaling theory. Potential clients who didn’t know me would most likely gauge my prowess by the way I dressed and the car I drove, making it easier to attract lucrative business. If I were running a scrap yard, I would purposely choose a beat down car or pickup truck to fit in with my clients so they didn’t think I was making too much money. That is another example of how opportunity cost could factor into your decision in ways that might be unexpected.