Video Games May Seem More Expensive But They Aren’t – It’s All In Your Head

Like most things on this site, this isn’t really about video game prices at all. It is a lesson in economics and how to think about the world if you want to be successful.

I have been hearing a lot of grumbling lately from friends and fellow gamers about the cost of video games. The economist in me cringes when an otherwise rational person jumps into a diatribe on the state of video game pricing and the various console wars because it reminds me of those people who insist that gas is at an all-time high, even when the inflation-adjusted cost of traveling one mile is less than it was in the 1950s. Listening to it makes me realize how thoroughly our education system has failed at producing rational, informed citizens capable of competing in the information age where knowledge is power.

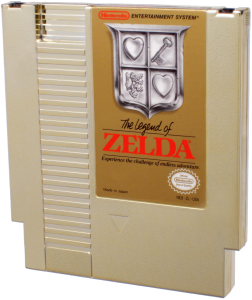

In 1986, The Legend of Zelda was released with a retail price of $49.99 plus tax, or $53.49 in the Kansas City area. To adjust that for inflation, the game would have to sell for $109 after tax today.

When it comes to video games, or any other form of media for that matter, what counts is the net cost per hour of entertainment delivered, adjusted by the subjective enjoyment of that entertainment for the person experiencing it. The sticker price for the game itself doesn’t matter. If you buy a game that costs $5 and delivers 10 hours of gameplay that you are crazy about and loved, your expense was around 50¢ per hour. If you buy a game that costs $100 and you get 200 hours of game play out of it that you loved, your cost was still just 50¢ per hour of being entertained.

Put more plainly, the $100 game cost the same amount as the $5 game because you aren’t buying a game, you are buying hours of entertainment. That is what you are paying for when you open your wallet. That is what the video game developer needs to deliver.

The Real Price of Video Games Has Plummeted Over the Past 30 Years

This basic economic truth aside, the inflation-adjusted sticker cost of video games has plummeted over the past three decades.

Think about the $4.99 games sold in the Apple store for iPad, iPhone, and iMacs. Today’s consumers can own (or license, rather) a title for the cost of a few rounds of quarters shoved in video arcades, which is how our grandparents had to play. In addition, there aren’t all these layers of middlemen (e.g., the bowling alley operators) keeping a cut of the profit. Instead, for every $1.00 sold, the platform distributors such as Apple keep 30¢ and the game creators keep 70¢.

If you can develop a successful application or game, it is entirely possible that a few months from now you’d have six-figures in cash sitting in your bank account. That kind of rapid payoff wasn’t nearly as accessible in the past. The industry certainly wasn’t as democratic as it is now, where an individual, a married couple, or a group of friends can code and launch an app that pays off their house after going viral.

As for traditional console games, consider this: When The Legend of Zelda was first released in 1986 on the Nintendo Entertainment System, it retailed for $49.99 plus tax. In the Kansas City area, you’d be looking at around $53.49 to take the game home from your local Toys ‘R Us at a time when President Reagan was in office, the Challenger space shuttle had blown up, and Chernobyl was melting down in Europe; the stock market was recovering, in the early phases of the biggest boom in recorded history, and young upstarts like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were already rich from their early days in the computer industry.

Adjusted for inflation, if The Legend of Zelda were released today, it would sell for $109 after tax at your local Walmart, Target, or GameStop.

To complain about a game of comparable scope selling for $60 today, complete with vastly superior graphics, sound, and gameplay immersion, is an economic fail. Even adding in $40 of downloadable content for expansions and full functionality in games like Dragon Age or Castlevania: Lords of Shadow still only gets you to $100, which is cheaper than the real cost of the original Nintendo Entertainment System games.

The question, then, is, “Why do video games seem more expensive?” Simple. When you were a kid, your parents were picking up the tab. Now, you have to buy them yourself. People are a lot more selective and protective of their own hard earned money than they are when they spend someone else’s cash.