An Overview of How I Research Stocks

Some of you had asked me to explain how I research stocks – specifically, where I look for investment ideas, which data sets I use, and how I find potential holdings for the portfolios I manage for my household and businesses, including the only one discussed on this site, the KRIP portfolio, which is stuffed with high-quality dividend paying blue chip stocks. Before I got to my other work today, I wanted to sit down and take some time to give you a broad outline of the research process so you can better understand what it is I am often looking for when I take out the checkbook. I had touched on this before in how to find a list of stocks for your portfolio, but I’ll give you the full rundown here.

Before We Talk About How to Research Stocks, We Need To Get The Philosophy Right

First, you need to understand that I approach the process of researching stocks the same as I do when I look at any of the private businesses in which I hold an investment. Most of my success has been the result of owning companies that I started, or in which I was an original investor. In my case, almost all of these are structured as either a limited liability company or a limited partnership, most of which I never mention on the site. In fact, my 2011 Federal tax filings show $0 in wages or salaries (which is really just another way of saying “selling your time”). All of my money comes from business activities, investments, dividends, rents, and interest income. Personally, I also generate a considerable amount of money licensing my written content, which is a fun, albeit lucrative, hobby.

When you research stocks, you are really researching a business.

Often, we need a place to “inventory” these profits. For our purposes, we consider publicly traded stocks right alongside anything we could do ourselves. Why start a restaurant if McDonald’s is trading at an earnings yield equal to 3x the Treasury bond rate? (It’s not, by the way. I wish it were.) Why open a jewelry store if you can get Tiffany & Company at a dividend adjusted PEG ratio of less than 1.00? (Again, that’s not what the market is offering as of today.) When we research stocks, we have the mission of finding places to invest our capital so that it generates cash, compounds that capital, and accumulates ever-increasing streams of profit. This model is not unique to us. One of my favorite stories is of a man named Miller Gorrie, who built his entire fortune on the back of a block of IBM shares he accumulated early in life.

In fact, a “stock” is just a business. Nothing more. Nothing less. So even the concept of how to research stocks is a bit misguided. What you are really interested in is finding businesses in which you want to become an owner, at an attractive enough valuation that it offers you the promise of a good return even if results are mediocre, and run by a management team that treats your capital with respect. The goal behind evaluating a local car wash or shares of Johnson & Johnson is exactly the same to me. I am interested in creating risk-adjusted, inflation-adjusted, after-tax increases in real wealth, as measured by higher purchasing power. All else equal, I don’t particularly care if I own a local apartment building or if I buy shares of one of the Dow Jones Industrial Average components. For that matter, if bonds were offering a higher return, I’d be parked in bonds.

That means that when I research stocks, I am thinking of equities as one potential asset into which I can invest my capital. Going back to McDonald’s, if I were able to acquire the McDonald’s franchise in my hometown for an incredible bargain (an unlikely prospect since the McDonald’s Corporation would just buy back the business for its corporate portfolio), I’d liquidate stocks to do it. Every investment opportunity is competing for our dollars.

There have been periods where I bought almost no stocks, and other times when I do everything in my power to accumulate large positions that I want to hold indefinitely. Just last week, I sold off a block of Berkshire Hathaway shares, despite believing they are considerably undervalued, in order to fund my buyout of the other members in one of my private businesses. I expect Berkshire to do very well over the coming decade. There is no guarantee of it, but I think the data supports that probability. However, I think it is more than assured that I will generate a significantly higher compound annual growth rate by acquiring the membership units of my fellow investors, who are about to enjoy a very lucrative payday.

That means when you research stocks, you need to begin with the premise that your job is not, necessarily, to buy stocks. Your job is to grow your money and stocks are merely one possible mechanism through which you can achieve that objective.

The 5 Ways I Research Stocks

When it comes to actually researching stocks, there are typically five ways I come across new investment ideas, each of which I will address in-depth. This isn’t everything, but it covers the waterfront.

- Focused searches in specific industries at specific times

- Browsing research data sets and periodicals looking for anything interesting

- Running targeted screens for specific criteria

- General curiosity about the world, which leads to some interesting opportunities

- Disclosure documents

The big thing you need to understand is that you shouldn’t wait until you have cash to begin researching stocks. There is no way you can educate yourself in a day, or even a week, about certain industries or operations. You need to be constantly looking, storing ideas and models in the back of your mind so that you are ready to act when capital finds its way into your hands.

1. I Research Stocks By Looking at Specific Industries at Specific Times

From time to time, different industries or sectors of the economy will be out of favor or about to experience a large increase in profitability. Sometimes, investors are just bored with a particular type of enterprise. During the banking crisis, for example, my family knew that banks would have to exist, in some capacity, following the disaster. We studied a wide range of bank holding companies and determined that two likely to survive intact, and with much stronger competitive and capital positions, were U.S. Bancorp and Wells Fargo & Company. We bought, and kept buying, ownership. My personal family portfolio holds shares of both, and has for years.

In other words, as the banking sector was falling apart, we went shopping for banks to own. We began by researching stocks with the strongest Tier 1 capital ratios, then excluding those with large counter-party risks. This approach requires wisdom because it isn’t always a good idea – virtually all of the manufacturers of asbestos ended up going out of business or seeking bankruptcy protection – but done right, it can lead to significant wealth accumulation.

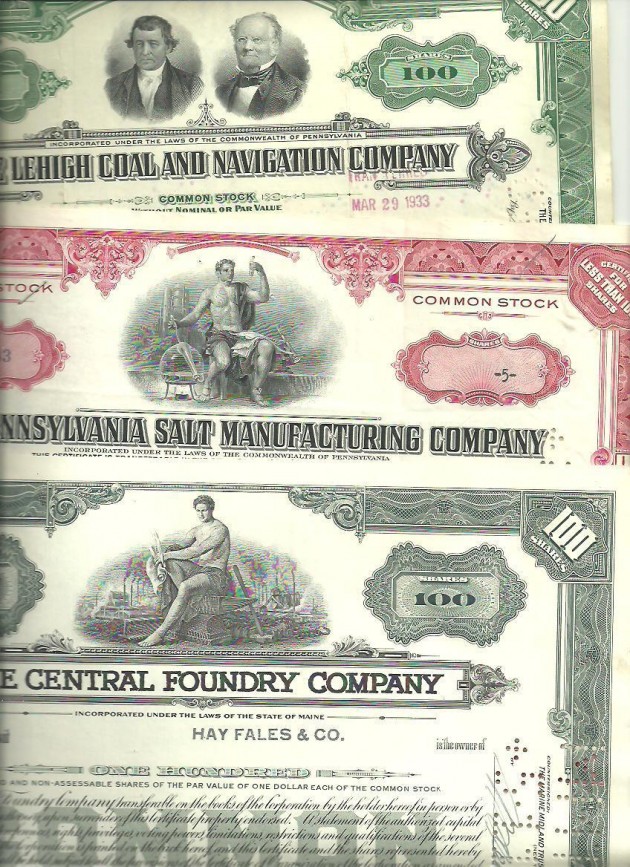

2. I Research Stocks By Browsing Various Publications and Data Sets

One of the great joys in my life is spending an afternoon, alone, completely uninterrupted, with a fresh cup of hot, black coffee, sitting on the upper deck of my home reading through publications such as the Value Line Investment Survey or the Value Line Small & Mid Cap. I almost always reorder the annual edition of the S&P 500 tear sheets. There have been times that I have published pictures of the process. Seeing what companies do, how they function, how they are structured, and how they evolved through history appeals to the inner detective, sociologist, and economist in me. You run into some really cool historical quirks, such as a royalty unit trust created by a railroad bankruptcy in the late 1880s that still produces income for its holders. I like stuff like that.

Whenever I find a company that fits the list of desirable traits – a historic record of raising dividends, earning high returns on capital with little or no debt, having a strong competitive advantage in the market place, a history of little to no share dilution, and room to grow – I add it to a list of companies that I want to own but am waiting on valuation. Sometimes, I’ll pick up a few thousand dollars worth of it and stick it in one of the family’s portfolios just to keep an eye on it.

Some of my favorite resources are the specific trade publications you find in one area of business activity. For example, there is no better way to research insurance companies than the A.M. Best manuals, which you can then use to find promising candidates, after which you would order copies of their regulatory filings with the statutory insurance regulators (not the SEC) because those are more stringent in accounting standards and give you a better idea of true intrinsic value and loss development. If I were looking at restaurants, I like reading QSR magazine, which is geared toward the quick service restaurant business. You can find promising upstarts there. I have trade publications that detail statistics for various newspapers. I have a massive, multi-thousand page book that breaks down the deposits, assets, and liabilities of the various bank holding companies in the United States. There are days I just open one and start reading.

Trade publications are your friend. They are useful because they are written by, and for, the people in the industry. I mean, if you wanted to research stocks in the timber industry and planned on making a significant financial investment, you probably want to be on the reading list of the Timer Trade Journal, which has been the source of knowledge for the business since 1873. The odds are good that you are going to know more about what is going on in timber, both the good and the bad, faster and more efficiently than you can discover through your broker or The Wall Street Journal (as great as that publication is).

You never know what is going to come in handy from the knowledge you accumulate this way.

3. I Research Stocks By Running Targeted Screens for Specific Criteria

Sometimes, I will research stocks by running screens looking for traits that have historically correlated with very good investment returns over long periods of time. For example, I might want to find companies that have dividend yields of more than the Treasury rate with payout ratios of less than 50% and returns on equity of more than 12% with little or no debt. I might want to find companies that have been radically improving asset turns over the past few years, or who have reduced liabilities significantly. I might want to find companies that have a history of raising their dividend by more than 15% over a decade, which might bode well for the health of the underlying business in terms of proving the cash is real. I might want to research stocks in which the executives are making large open market purchases with their own cash.

Then, I’ll put all of the results in a spreadsheet and work my way through the companies on the list, one-by-one. I’ve found some of my best performing stocks by doing this.

4. I Research Stocks By Having a General Curiosity About the World

You can’t believe how many companies you come across when you start paying attention to life. Generally speaking, if we walk into a room, a restaurant, a movie theater, or a conference, I can tell you who made, sold, or profited from the products you see. You should know that Coffee-Mate is a subsidiary of Nestle, that the bowl of Quaker Oats is going into PepsiCo’s coffers, that Lysol belongs to Reckitt Benckiser in the United Kingdom, or that Dial soap belongs to Henkel in Germany. Start picking up bottles and packages and looking at the fine print. Then, from there, figure out who makes the packages for the companies. Or who handles the logistics. Or who has the advertising account. In the words of Charlie Munger, all of life is “one interconnected damn mess”. It’s a web. Everything is connected to everything else.

An example would be the tour I took of the candy company in Denver. I actually noted the business names on the packages of raw ingredients and supplies so that I could research them, too. I look at the names on the machinery. Basically, an insatiable, never-ending curiosity is your ally. I love studying how things work and how they are put together to form cohesive systems.

5. I Research Stocks By Going Through Disclosure Documents

There are a few dozen investors on the planet of whom I am aware who have the same philosophy I do when it comes to capital allocation, and who have personalities that lend themselves to buy the same types of businesses I’m interested in owning. Some of these investors have their holdings disclosed to various government agencies and, if you know where to look, you can find out what they are buying and selling. If I see a specific company constantly coming up as a common denominator, it will attract my interest enough to go through the 10K and annual report. I’m not going to tell you who these people are, or where you can find their holdings (other than the obvious SEC Form 13-F filings) – where would the fun be in that? – but only that it is possible.

Putting It All Together To Create Your Own Stock Research Process

For me, those five things work together to create a system that results in “the spreadsheet” or “the list”, for lack of a better term, which is a collection of companies that I want to own, at the right price. Every year or so, I will re-read the annual report (once a company makes the spreadsheet, it is almost always on the radar), and then come up with a rough estimate of intrinsic value. I will then have the market price monitored against this estimate of intrinsic value, with the spreadsheet re-ranking itself by the firm that offers the most value for the money at the time. It shows the dividend adjusted PEG ratio, the return on capital, the difference between the base earnings yield and the 30-year Treasury bond yield, and a host of other information. I then standardize these stocks using a process I describe in the post called A Technique for Comparing the Intrinsic Value of Two Stocks. There are some modifications – companies with high returns on capital are weighted more favorably due to the superiority of the business – but that is the general premise.

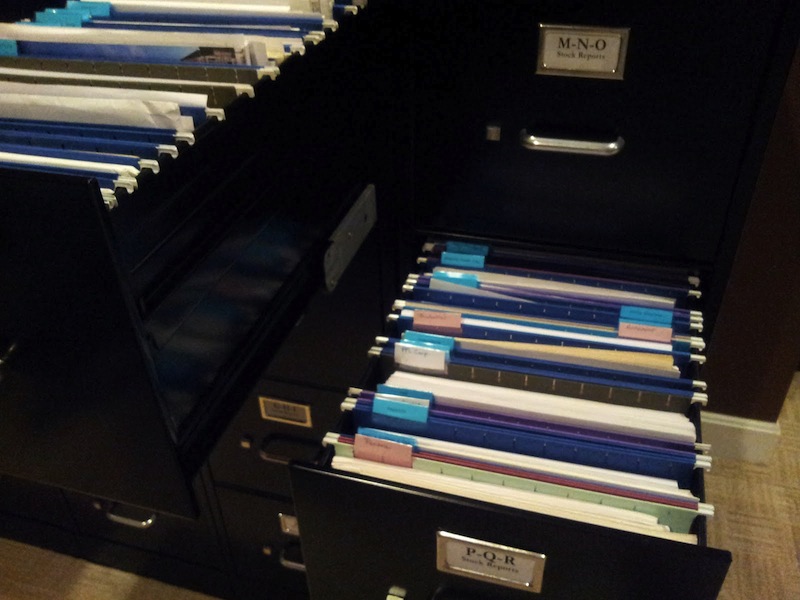

Each of the companies on the list is given its own file, with my notes on the business. I can see how I thought about things in the past, with some of the files going back more than a decade. I have around half a dozen file cabinets that house the collection and they are updated on an on-going basis. The spreadsheet probably contains a couple hundred stocks.

The file cabinet of research stocks that I keep that made it onto the monitor list … the companies in which I actually have an investment are pulled out and put in a much larger file cabinet in my office. The general rule is I never allow the portfolios to contain fewer than 10 or more than 50 stocks. The top 5 or so positions tend to make up over 50% of the portfolio.

Of those research stocks, a handful (at the present time, approximately 10) of companies may get flagged as “permanent” or “indefinite” holdings, meaning we have no intention of selling if and when we purchase (though, again, future conditions could change and modify that). Even if they are not quite as cheap as something else, I will acquire more shares, stick them in a vault, and collect cash dividends for decades whenever they are within striking distance of fair value. It takes an exceptional act or situation to even consider liquidation of the permanent holdings. For example, no matter how bad the economy gets, I can’t foresee a situation in which my ownership of Johnson & Johnson or Nestlé doesn’t increase with time.

As for the actual packet we put together when we research stocks, I explained that here and posted pictures.