Thoughts on Berkshire Hathaway’s Intrinsic Value – 2015 Edition

Three years and seven months ago, I wrote about the intrinsic value of Berkshire Hathaway. At the time, the stock price was $73.17 per Class B share and we had been buying quite a bit of it throughout the year. I spelled out my reasons for believing the stock was trading for “far less than intrinsic value” and argued (in a rare change for me given I’m usually more, not less, conservative than most analysts) that the analysts and research houses covering the stock, Morningstar in particular, had significantly underestimated the economic engine and real earnings of the firm. Within four months of that post being published, Morningstar revised their intrinsic value figure to something I considered more reasonable.

One of the reasons I found it attractive was the fact that an owner buying at that price could wait 12 to 18 months and find himself or herself in a position of having a cost basis below book value. In many cases, book value doesn’t matter because a firm has engaged in huge repurchase programs that change the utility of shareholder equity for this sort of analysis; e.g., AutoZone. Sure enough, that happened on schedule. The past few years have been so good at the operating level that as of the end of first quarter, book value now exceeds that $73.17 price by 35.775%, coming in at $99.34 per share.

The market value has become more reasonable and the shares trade at $145.26 each, representing an unrealized gain of $72.09, or 98.52%. At one point, the gains on the Berkshire Hathaway and Wells Fargo holdings in the KRIP pushed those two stocks alone past the 52% of holdings market, which is not my idea of prudence so, despite them still being cheap, I engaged in what I call horizontal risk shifting and sold some off, especially in tax-free accounts so I wouldn’t lose any deferred tax benefit, buying up other great businesses that offered the same discount-to-intrinsic value and underlying economic prospects.

A year and two months ago, I posted an annual review of the results explaining that I had been having my own family, including my extended family members, continuously buy up shares for the accounts mentioning that the last purchase had occurred on February 11th at $112.61 per Class B share. In our accounts, the other stocks had blown past Berkshire Hathaway, making it a relatively smaller position so I felt comfortable from an allocation perspective buying more.

So here we are. Berkshire Hathaway represents the 5th largest position in the KRIP (it dropped a couple of relative weight rankings due, in part, to significant additions to two other holdings in the past nine months, including Diageo, PLC, which I’ve been buying like crazy over the past seven months). It’s at $145.26 per share in market value. It has a book value of $99.34 per share. There are 2,464,547,053 Class B equivalent shares outstanding. What do I think of the insurance, energy, and transportation conglomerate these days?

Berkshire Hathaway’s Earnings Power Has Increased Tremendously Over the Past Decade

Surveying the most recent ten year period, the increase in Berkshire Hathaway’s economic engine has been breathtaking. The Great Recession of 2008-2009 gave it the opportunity to lay out billions upon billions of dollars in cash it had been storing for years prior at terms that were unlike any deals we’ve seen in decades. Convertible preferred stocks, warrants, private buyouts … the firm got its on hands highly lucrative securities, many of which were privately negotiated and offered return enhancers not available to average investors; businesses such as Bank of America, Dow Chemical, General Electric, Burger King / Tim Horton’s, H.J. Heinz, and Goldman Sachs. Its outright acquisition activity added substantially to the earning power. It’s true that the real fortunes are made during collapses as those with foresight gobble up assets on the cheap.

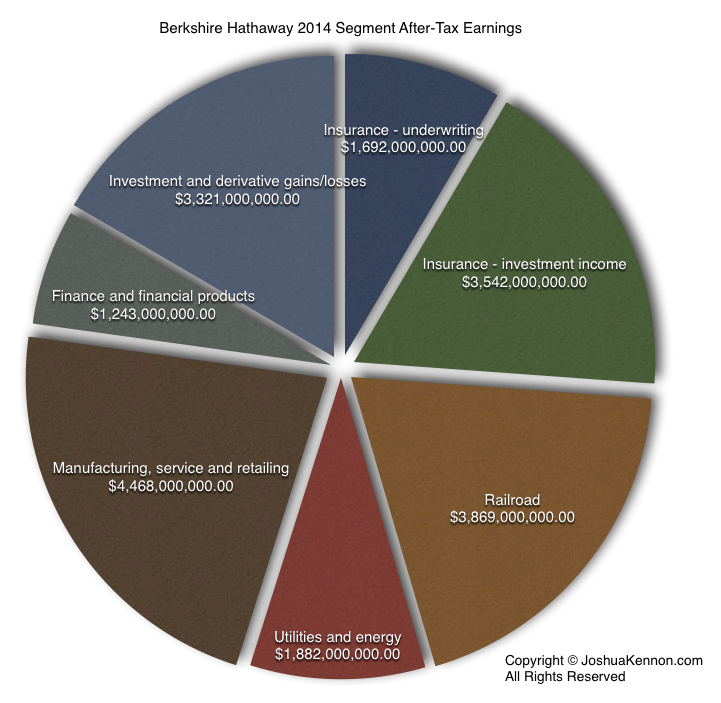

On page 86 of the annual report, you find the after-tax profit by segment for 2014. Leaving aside the $145 million expense for “other” (which matter but are a rounding error in this case so for simplicity, we can discard it for the time being) the net earnings came to $20,017,000,000.

However, as mentioned on page 6 of the annual report, there is another $3,300,000,000 in net income not included due to accounting rules. These are the non-distributed retained earnings generated by stock positions in the equity portfolio; e.g., the profits from Coca-Cola, American Express, IBM, et cetera that were not paid out as dividends. Since Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t own enough of these businesses to qualify for tax-free dividend payouts like it can with its controlled subsidiaries, there would be some tax hit were that money to be sent to headquarters but it’s still a whole lot of purchasing power that belongs to Berkshire Hathaway not showing up in the earnings per share figure or the pie chart (see below). That matters.

Adding back some other small items, this means when you look at Berkshire Hathaway’s earnings per share for the Class B stock, it comes to $8.06 + non-recorded look-through earnings on the common stock portfolio. Leaving aside those non-recorded look-through earnings that are every bit as real as the other profits, the current price-to-earnings ratio on the stock is 17.99x, representing an earnings yield of 5.55%. That’s not directly comparable to other operating businesses because that $8.06 doesn’t represent underlying operating earnings but, rather, is influenced by the investment portfolio, which can fluctuate wildly year-to-year depending upon dispositions and market conditions.

Berkshire Hathaway is sitting on almost $60 billion in cash (with a $20 billion minimum necessary for operations, this represents around $40 billion in surplus money sitting there, earning nothing, that could someday be put to use with lightning speed), real earnings and assets are higher than they appear once you dig through the accounting rules, and the utility segment is almost certainly going to expand drastically in coming years since it represents an opportunity to put to work the tens of billions of dollars being pumped out from the furniture stores, jewelry stores, insurance underwriters, candy companies, mobile home manufacturers, and other enterprises. (There aren’t many other sectors capable of absorbing that kind of capital in a meaningful way while generating good returns. Absent some sort of unforeseen change in market conditions, I think it’s only natural it’s going to come to represent a far larger percentage of the pie over time. There is still a lot of potential for future growth. The same goes for the railroad. Union Pacific, BNSF’s major competitor, is significantly more profitable. It can make a lot more money if it’s managed well, especially now that it has Berkshire’s enormous financial backing.)

Long story short, if you asked me to come up with my estimate of intrinsic value per Class B share, I’d say with a high degree of certainty it sits somewhere between $160 and $170. If you could get your hands on the entire thing (not many folks in the world are capable of such a feat), you could pay a bit more and do fine. The implication is clear that I think it’s still undervalued at a market price at $145.26. Though nothing in this life is certain – crazy things happened and even great empires fail – a person buying today, at this price, should have reason to be fairly confident that he or she might enjoy a satisfactory outcome after 10+ years have passed.

Specifically, you can’t predict the timing of market prices with any certainty – it’s a fool’s errand so don’t even try – but you can probably say that absent some sort of major unexpected event or conditions, Berkshire Hathaway’s intrinsic value per Class B share should be no less than $350 and no more than $500 ten years from now, adjusted for any subsequent dividend payouts. To move beyond either side of those ranges, you have to assume a lot of things go very wrong, or very right. Modeling for almost all reasonable growth rates, economic conditions, likely interest rates, and other variables puts you within that proximity.

Conclusion: Were I constructing a portfolio with new money, Berkshire Hathaway shares would be on the purchase list. It’s not nearly as expensive as some other firms and also seems reasonably valued on an absolute basis. You don’t have the right to expect more than this out of the capital markets. This is what fair looks like. In fact, I plan on having some of my friends and family buy more in the coming months if the current market price (or lower) is still available as their regular deposits arrive for me to put to work. I may even pick up some for my own accounts but there are two or three other businesses I’ve been wanting to add as cash levels replenish following the Diageo purchases.

I Do Wonder Why the Regulators Haven’t Considered Breaking Up Berkshire Hathaway

One question I have – and maybe I’ll write more about this someday – is why regulators haven’t broken the place up, yet. Despite my lifelong love of Berkshire Hathaway, and my very real own financial self-interest in seeing it kept together, any intellectually honest self-reflection requires me to admit that, while it doesn’t fit the technical definition of a “systematically important financial institution” as far less than 85% of its revenues come from finance or money related activities, no rational civilization should be content with the sort of concentration of economic and political power that has found its way into Omaha.

This is a single firm that now wages staggering influence in nearly every sector of the American economy. It controls major energy production and pipelines; transportation and distribution businesses; insurance empires; it holds major ownership or warrants in American Express, Wells Fargo, U.S. Bancorp, Moody’s, Munich Re, and Goldman Sachs. It sells $13 billion or so per year in merchandise to Wal-Mart while simultaneously holding 2.1% of Wal-Mart’s shares, excluding its cut of indirect sales from its huge Coca-Cola stake (and, for years prior to the scheduled exchange, Procter & Gamble). It holds majorly influential financial positions in Dairy Queen, Burger King and Tim Hortons, along with Heinz-Kraft and the distribution business, McLane, which counts among its major customers Yum! Brands’ KFC, Taco Bell, Pizza Hut, and Long John Silver’s franchises.

I love all of these profits coming in, and have been significantly enriched by them due to a habit of buying for most of my adult life whenever conditions were favorable, but as a citizen, the anti-competitive concerns are huge for me on a personal level. If Teddy Roosevelt were alive he’d have taken a 2×4 to the place and I can’t say I’d blame him. What sane society thinks this is permissible? The potential for abuse is even greater than at larger firms like Exxon Mobil due to the nature and specifics of the holdings. Reading the annual report this year, I felt for the first time not a sense of pride, but of shame and a whisper in the back of my mind: “This shouldn’t be permitted to exist.” There’s something that strikes me as immoral about it, whereas I don’t feel that way about McCormick holding 50% of the domestic spice industry because it’s contained within the spice industry itself.

I know Warren wrote about the disadvantages of a breakup or spin-off (especially as it pertains to tax law) in his follow-up 50 year anniversary special letter after the actual annual stockholder but he conceded that a regulatory distribution might someday be required as it was with the company’s bank a few decades ago. The only saving grace is the wisdom Buffett and Munger have displayed in keeping leverage so low and maintaining “oceans of liquidity” as he so accurately put it. I get the sense, in a very real way, the only reason it’s given a pass is because of their influence and historical record for good stewardship, citizenry, and regulatory cooperation. Were anyone else at the helm … I’m not so sure it would avoid scrutiny. I’m not so sure it should.

Update: Several years ago, I placed this post, along with thousands of others, in the private archives. The site had grown beyond the family and friends for whom it was originally intended into a thriving, niche community of like-minded people who were interested in a wide range of topics, including investing and mental models. On 05/22/2019, I decided, after multiple requests, to release selected posts from those private archives if they had some sort of educational, academic, and/or entertainment value. This special project, which you can follow from this page, has been interesting as I revisited my thought processes about a specific company or industry, sometimes decades later. In this case, reading about how we approached the analysis of a real-world business was helpful to many of you and the information contained herein is now so old there is no chance a reasonable person might mistake it for current market commentary.

One major change that has occurred in the years since this post was originally published: Aaron and I relocated to Newport Beach, California in order to have children through gestational surrogacy. Within a window of a couple of years around that relocation, we also sold our operating businesses and launched a fiduciary global asset management firm called Kennon-Green & Co.®, through which we manage money for other wealthy individuals and families. That means we are now financial advisors (or, rather asset managers operating under an investment advisory model as we are the ones making the capital allocation decisions rather than outsourcing those to fund managers or third-parties), which was not the case at the time this was written. Accordingly, let me reiterate something that should be perfectly clear: this post was not intended to be, and should not be construed as, investment advice. Also, for the sake of full disclosure, I’ll state outright that Aaron and I still own shares of Berkshire Hathaway personally and that the stock represents one of the major equity holdings of our firm’s private clients. We express no opinion as to whether or not you should buy it. Any company can do poorly or even go bankrupt. There are no guarantees Berkshire Hathaway will generate a profit or make money for shareholders. We may buy or sell Berkshire Hathaway for ourselves or our clients in the future and have no obligation to update this post or any other historical writing. You should talk to your own qualified, professional advisors about what is right for your unique circumstances, goals, objectives, and risk tolerance.